Der

Fuhrer, Adolf Hitler

A Reich is really just another way of saying government. It’s more or less saying 1st government, second government and so on. So in reality the

Fourth Reich exists but as a republic. The term also exclusively applies to the modern German state and its previous incarnations (German empire, Weimar and the Nazi regime)

Nazi Germany is also known as the Third Reich (Drittes Reich), meaning "Third Realm" or "Third Empire", the first two being the Holy Roman Empire (800–1806) and the German Empire (1871–1918). The Nazi regime ended after the Allies defeated Germany in May 1945, ending World War II in Europe.

Third Reich, is the name given by the Nazis to their government in Germany; Reich is German for “empire.”

Adolf Hitler, their leader, believed that he was creating a third German empire, a successor to the Holy Roman Empire and the German empire formed by Chancellor Bismarck in the nineteenth century.

In effect a New World Order.

The ‘Underground Reich’ is an entity which maintains the long-term interests of German-based multinational conglomerates, it includes heavy industry, chemicals, communications, as well as international shipping, banking and financial

interests - like every other empire. Emory contends that the many units which make up the “Underground Reich,” having survived

World War II, persist and flourish as major components of the current global capital elite”

Argentine journalist Uki Goñi conducted some two hundred interviews and undertook six years of relentless digging in archives in the United States, Europe, and frequently uncooperative ministries in Argentina. His findings are a catalog of cynical malfeasance and cover-up by highly-placed officials in the Argentine government and the Catholic Church, as well as actors from other countries. Goñi’s principal contribution is his in-depth look at the Argentine side of an organized smuggling operation that had its genesis in German-Argentine cooperation during the war and eventually involved Allied intelligence services, the Vatican, and top Argentine officials in network stretching from Sweden to Italy.

Among the key players in Goñi’s account are two Argentines of German descent: former SS Captain Carlos Fuldner, who ran “rescue” efforts from bases in Madrid, Genoa, and Berne; and Rodolfo Freude, head of Perón’s Information Bureau, who coordinated the work of intelligence and immigration officials from his office in the Casa Rosada, Argentina’s White House. Many of the Argentines involved, as well as a multinational cast of Vichy French, Belgian Rexists, Croatian Ustashi, and cardinals from several countries, seem to have been motivated by the vision of an international brotherhood of Catholic anti-Communists.

OPERATION PAPER CLIP - NAZI ORIGINS OF THE CIA

Throughout the Second World War, Nazi Germany maintained a particular technological superiority over its adversaries in the creation of chemical weapons and reaction technology, medicine, and aerodynamics and rocketry (the V-1 and V-2). As the Allied forces advanced into Germany during the final stages of

World War II, the race was on between the United States and the Soviet Union to seize as many German scientists as possible in anticipation of the Cold War. Through the efforts of a newly formed and highly secretive government organisation, The Joint Intelligence Objectives Agency (JIOA), Operation Overcast (later renamed Paperclip) was launched; its objective – to recruit and smuggle into the United States 1,600 German engineers and scientists, many of whom had worked for the Third Reich and had been leaders of the Nazi regime.

Notably, President Truman had publicly forbidden the recruitment of anyone who was a member of the Nazi party or was more than a nominal participant in its activities, thus rendering many of the scientists ineligible. To circumvent this restriction, the files of such recruits were altered by the government, and the only evidence of their Nazi past was in the form of the paperclip that had attached their original files to those being whitewashed.

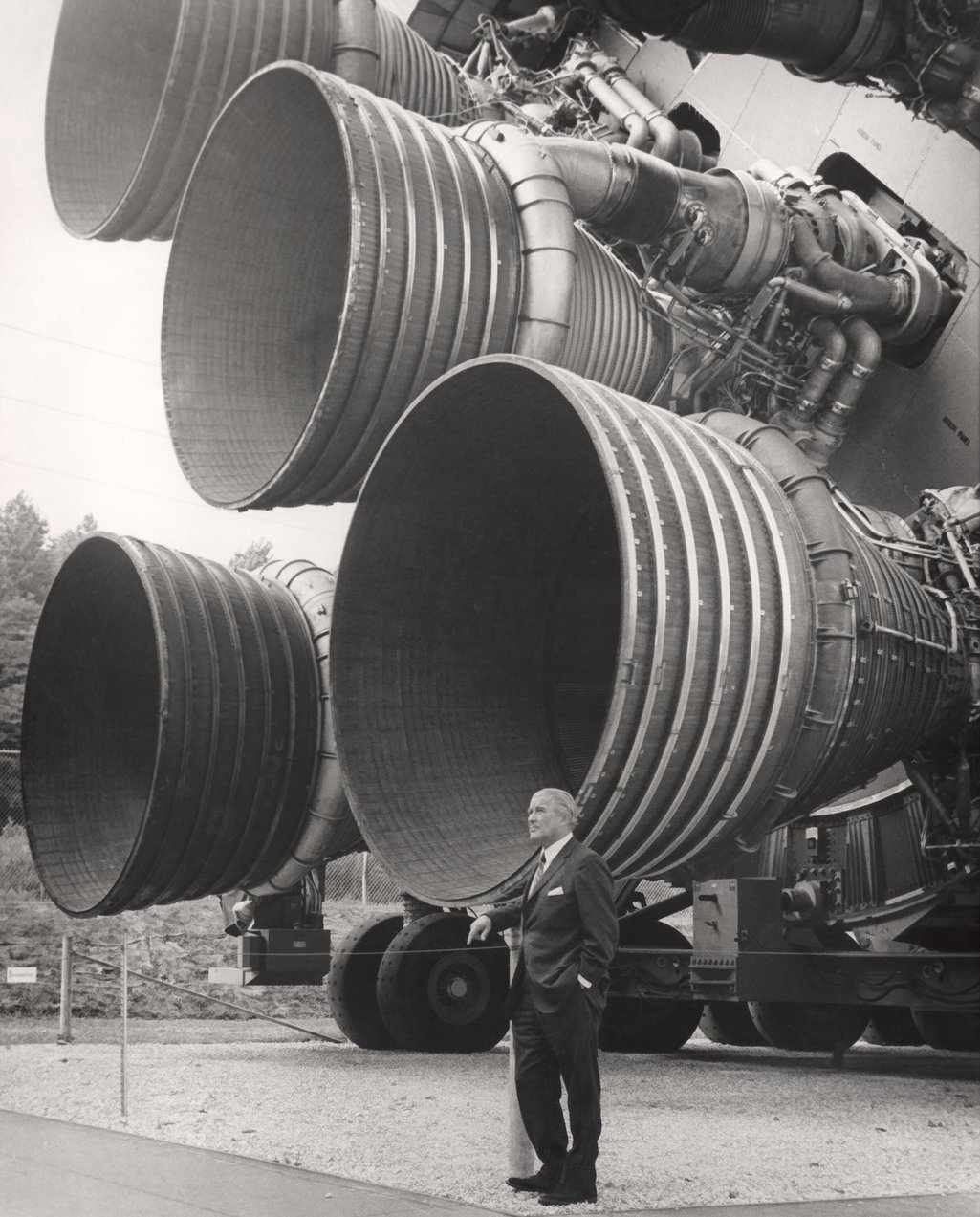

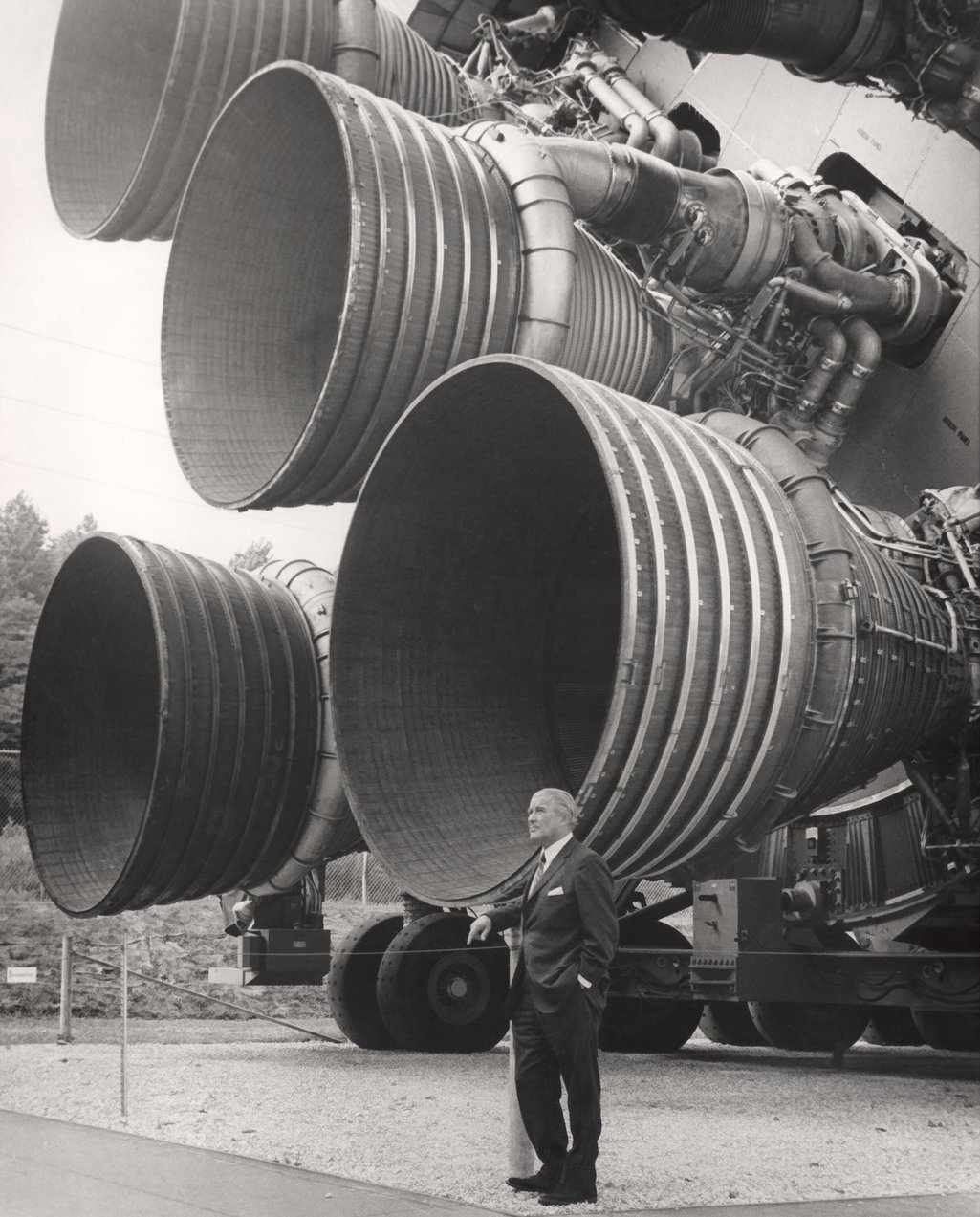

The Space Race between the United States and the Soviet Union was a remarkable time in history, when the world’s two superpowers competed bitterly in a series of technological initiatives to demonstrate their superiority in

space flight. Many of the scientists recruited through Operation Paperclip were instrumental in the United States nuclear and space programmes, of whom probably the most infamous, with ties to the Nazi war machine, was Wernher von Braun, the aeronautics engineer behind one of Germany’s potentially most effective weapons – the V-2 Rocket. Von Braun became an integral part of the United States weapons and space programmes, eventually becoming the director of NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Centre and the chief architect behind the Saturn 5 launch vehicle, responsible for sending US astronauts to the moon.

Further controversy arose in the mid-1970s, when over 20,000 CIA documents became public, detailing covert attempts to develop psychological, biological, chemical, and even radiological procedures to turn both foreign and domestic spies into sleeper agents. During the early stages of the Cold War, the

CIA were convinced that communist regimes had discovered drugs and techniques that enabled them to control human minds for intelligence purposes. In response, MK-ULTRA was established, a highly classified project in which the

CIA conducted clandestine experiments, sometimes on unwitting subjects, to assess the potential of LSD and other drugs in mind control techniques that could subsequently be used against enemies.

MK-ULTRA was not a single project, but a network of interconnected experiments, the most notable of which were the projects BLUEBIRD and ARTICHOKE that focused on

inducing amnesia to create hypnotic couriers and ‘Manchurian Candidate’ super spies. In addition, BLUEBIRD focused on behaviour modification and hypnosis to prevent agency employees from divulging intelligence to adversaries, and ARTICHOKE on creating post-hypnotic triggers by which sleeper agents could be activated from a state of ignorance about their assignments. As a matter of fact, MK-ULTRA was a continuation of work that had begun in Nazi concentration camps, which explains why the CIA specifically used Operation Paperclip to recruit the scientists for the project. The main contributors were Walter Schreiber, former Surgeon-General of the Third Reich, and Kurt Blome, leader of the

Nazi programme to weaponise Bubonic Plague.

MODERN

TIMES

Today, the idea of the Fourth Reich is synonymous with resurgent Nazism, but it is more ominous than ‘neo-Nazi’, as it designates something actual rather than merely aspirational. The Fourth Reich suggests that right-wing extremists are on the brink of power, or have already attained it. Ironically, the term actually had a very different meaning. The Fourth Reich was first used as a rallying cry in the 1930s by German opponents of the Nazi regime. The groups who employed the term spanned a broad political spectrum: from left-wing German exiles in Paris, who produced a ‘Draft Constitution for a Fourth Reich’ in 1936, to conservative monarchists, who spoke of a future post-Nazi Fourth Reich of Christian unity. Equally strange bedfellows were Jewish refugees in New York, who called their neighbourhood the ‘Fourth Reich’, and renegade Nazis belonging to Otto Strasser’s schismatic ‘Black Front’ organisation, who envisioned the Fourth Reich as a place where a ‘genuine’ National Socialism would one day be realised.

The term’s meaning changed dramatically after the Second World War. As Allied forces occupied Germany, fears that unrepentant Nazis would refuse to surrender – and one day seek to return to power – gradually transformed the term from one of hope to one of fear: a fear that was far from groundless. Although today Germany’s postwar democratisation is often seen as inevitable, in 1945-47 Nazi groups challenged Allied troops with various coup attempts. All of them were eventually suppressed, but their media coverage hyped the averted threats as harbingers of a possible Fourth Reich, changing the term’s meaning.

In the decades that followed, the Fourth Reich became the term of choice for activists who hoped to keep the western world vigilant about the evolution of West Germany’s fledgling democracy. When the Federal Republic faced neo-Nazi threats in 1951-52 – with the rise of the Socialist Reich Party (SRP) and the uncovering of the Nazi ‘Gauleiter Conspiracy’ – western newspapers actively warned of a possible ‘Fourth Reich’. The same was true around the time of the ‘swastika wave’ of antisemitic vandalism in 1959-60 and the rise of the far-right National Democratic Party (NPD) in 1966-69. Such warnings continued through the anxious years surrounding German unification in 1990. In short, the Fourth Reich was a probationary term, reminding Germans that the West had not forgotten the Nazi past.

The Fourth Reich was also applied to the US. Thanks to the racist backlash against the Civil Rights Movement, the escalation of the Vietnam War and the scandals of the Nixon administration, many on the political left claimed that a Fourth Reich was dawning in America. In a 1973 interview, the writer James Baldwin decried American voters’ decision to return ‘Nixon … [to] the White House’, declaring that: ‘To keep the n----- in his place, they brought into office law and order, but I call it the Fourth Reich.’

The term also penetrated US popular culture. Building on early postwar films, such as Orson Welles’ The Stranger and Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious (both 1946), a flood of novels, films, television programmes and comic books in the 1970s and ’80s showed Nazi villains pursuing a Fourth Reich across the globe. The premise has retained its resonance up to the present day.

It remains an open question how we should view the spread of the Fourth Reich as a political signifier. In many ways, it reflects the trade-offs that accompany the use of Nazi analogies today. As we struggle to understand and confront the emergence of right-wing political movements in the West, we face the dilemma of responding with excessive alarmism or excessive complacency. Too many hyperbolic comparisons – for example, between Donald Trump and Adolf Hitler – dulls the power of historical analogies and risks crying wolf. Too little willingness to see past dangers lurking in the present risks underestimating the latter and ignoring the former.

A

- Z OF NAZI GERMANY

|