|

HISTORY OF EUGENICS

- In 1907, the eugenics Education Society was founded in Britain to campaign for sterilisation and marriage restrictions for the weak to prevent the degeneration of Britain's population.

In 1931, Labour MP Archibald Church proposed a bill for the compulsory sterilisation of certain categories of 'mental patient' in Parliament.

Meanwhile from 1907 in the United States, men, women and children who were deemed 'insane, idiotic, imbecile, feebleminded or epileptic' were forcibly sterilised, often without being informed of what was being done to them.

By 1938, 33 American states permitted the forced sterilisation of women with learning disabilities and 29 American states had passed compulsory sterilisation laws covering people who were thought to have genetic conditions.

During

WWII Nazi Germany took Eugencis to the next level with mass

murder in gas chambers.

All legislation was eventually repealed in the 1940s. Or was it?

Eugenics is a set of beliefs and practices that aims at improving the genetic quality of a human population. The exact definition of eugenics has been a matter of debate since the term was coined by Francis Galton in 1883. The concept predates this coinage, with Plato suggesting applying the principles of selective breeding to humans around 400 BCE.

THE

SPECTATOR

Quote: "The only way of cutting off the constant stream of idiots and imbeciles and feeble-minded persons who help to fill our prisons and workhouses, reformatories, and asylums is to prevent those who are known to be mentally defective from producing offspring. Undoubtedly the best way of doing this is to place these defectives under control. Even if this were a hardship to the individual it would be necessary for the sake of protecting the race."

— The Spectator, 25 May 1912

It’s comforting now to think of eugenics as an evil that sprang from the blackness of Nazi hearts. We’re familiar with the argument: some men are born great, some as weaklings, and both pass the traits on to their children. So to improve society, the logic goes, we must encourage the best to breed and do what we can to stop the stupid, sick and malign from passing on their defective genes. This was taken to a genocidal extreme by

Hitler, but the intellectual foundations were laid in England. And the idea is now making a startling comeback.

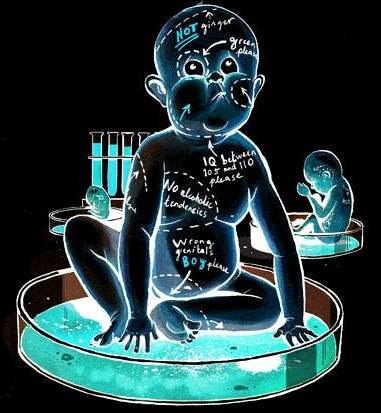

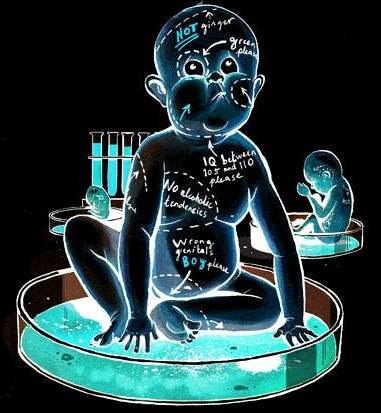

A hundred years ago the eugenic mission involved a handful of crude tools: bribing the ‘right’ people to have larger families, sterilising the weakest. Now stunning advances in science are creating options early eugenicists could only dream about. Today’s IVF technology already allows us to screen embryos for inherited diseases such as cystic fibrosis. But soon parents will be able to check for all manner of traits, from hair colour to character, and choose their ‘perfect’ child.

The era of designer babies, long portrayed by dystopian novelists and screenwriters, is fast arriving. According to Hank Greely, a Stanford professor in law and biosciences, the next couple of generations may be the last to accept pot luck with procreation. Doing so, he adds, may soon be seen as downright irresponsible. In his forthcoming book The End of Sex, he explains a brave new world in which mothers will be given a menu with various biological options. But even he shies away from the word that sums all this up. For Professor Greely, and almost all of those in the new bioscience, eugenics is never mentioned, as if to avoid admitting that history has swung full circle.

The word ‘eugenics’ was coined in 1883 by Francis Galton, a polymath who invented fingerprinting and many of the techniques of modern statistical research. He started with a hunch: that so many great men come from the same families because genius is hereditary. Fascinated by the evolutionary arguments of his cousin

Charles

Darwin, he wondered whether advances in health care and welfare had sullied the national gene pool because they allowed more of the sick and disabled not just to survive but to lead normal family lives. He went off to collect data, and came back with his theory of eugenics.

This was hailed not as a theory but as a discovery — a new science of human life, with laws as immutable as Newton’s. A race of gifted men could be created, he said, ‘as surely as we can propagate idiots by mating cretins’

Some of the most revered names in British history lapped this up. As Home Secretary, Churchill wrote to the Prime Minister urging him to do more to stop the “multiplication of the unfit”. Darwin himself would come to fear that “if the prudent avoid marriage whilst the reckless marry, inferior members tend to supplant the better members of society”.

By 1908, a Royal Commission conveyed the grave news that there were 150,000 ‘feeble-minded’ people in Britain. So what was to be done with them? As one reformer put it: “They must be acknowledged dependents of the State…but with complete and permanent loss of all civil rights – including not only the franchise but civil freedom and fatherhood”. This was William Beveridge, founder of the welfare state.

A report in The Times conveyed, matter-of-factly, the substance of a lecture given to the Eugenics Society following survey of the people of Devon by a Dr Grunby.

As to imbeciles, he said there was only one thing to do with them: exterminate them as they arose. He put forward the suggestion on purely humanitarian grounds.

Eugenics came to stand for modernity: to believe in it was to declare one’s belief in science and rationalism, to be liberated from religious qualms. Some of the most revered names in English history lapped all of this up. The Bishop of Birmingham called for sterilisation. Bertrand Russell looked forward to a eugenic era driven by science, not religion. ‘We may perhaps assume that, if people grow less superstitious, government will acquire the right to sterilise those who are not considered desirable as parents,’ he argued in 1924.

When a Sterilisation Bill was brought before Parliament in 1931 it had the backing of social workers, dozens of local authorities and the medical and scientific establishment. It was defeated, but the agenda continued. The Nuremberg Trials established that the Nazis (latecomers to all this) carried out some 400,000 compulsory sterilisations — a figure so horrific it has eclipsed the 60,000 in Sweden and a similar number in the United States. The idea of a biological divide between the fit and the unfit was no Nazi invention. It was the conventional wisdom of the developed world.

And this is the problem. Because we forget how badly Britain fell for eugenics, we fail to recognise the basic arguments of eugenics when they reappear — which they are now doing with remarkable regularity.

Consider Adam Perkins, a lecturer at King’s College London, who has published a study echoing the Royal Commission’s attempt to quantify the feeble-minded. The group he aims to study are the ‘employment-resistant’: those disposed to a life on welfare as a result of genetic predispositions and having grown up in workless homes. With Galtonesque precision, he estimates some 98,040 ‘extra’ people were ‘created by the welfare state’ over 15 years due to a rise in welfare spending. They represent an ‘ever-greater burden on the more functional citizens’.

In 1938, Germans were shown a poster of a cripple and invited to be angry about the costs of caring for him (60,000 Reichmarks). Dr Perkins tries a softer version of this general idea, calculating the £12,000-a-head annual cost of the new British untermensch — not just in welfare, but the crimes they will probably commit. His remedy? That Cameron’s government restricts welfare, so that claimants have fewer children. A perfect eugenic solution.

There is nothing monstrous about Dr Perkins, himself a former welfare claimant, nor anything very original about his book. He simply joins the dots of recent academic research and spells out what others won’t. His footnotes show the growing academic pedigree of the new eugenics: work has been done to identify genes relating to alcoholism, criminality, sporting success, even premature ejaculation. Extrapolations are now made about how far the quality of

human stock worldwide has been eroded by health care and welfare.

In academia, the word ‘eugenics’ may be controversial but the idea is not. To Professor Julian Savulescu, editor-in-chief of the Journal of Medical Ethics, the ability to apply ‘rational design’ to humanity, through gene editing, offers a chance to improve the human stock — one baby at a time. ‘When it comes to screening out personality flaws such as potential alcoholism, psychopathy and disposition to violence,’ he said a while ago, ‘you could argue that people have a moral obligation to select ethically better children’.

Meanwhile, the scientific pursuit of ‘ethically better children’ is advancing rapidly. Since Louise Brown was conceived in a laboratory 38 years ago — the world’s first IVF baby — the treatment has become mainstream, sought by 100 women a day in

Britain. Developments in IVF mean that, today, several embryos can be fertilised and screened for diseases, with the winner implanted in the uterus. The next step was taken last year, when Chinese scientists succeeded in modifying the genes of a fertilised embryo. It was rather messy: they attempted to treat 86 non-viable embryos, and failed in most cases. So they abandoned the experiment, saying a 100 per cent success rate is needed when dealing in human life.

This — the genetic modification of human embryos — is what causes the concern. But here, and at each point in the new eugenics, you can argue: where is the moral problem? There are no deaths, no sterilisations, no abortions: just a scientifically guided conception. The potential avoidance of disease, to the betterment of humanity. So who could complain?

One answer came many years ago, when 150 scientists and academics called for a complete shutdown of human gene editing. In a letter released before a summit in Washington DC, they argued that the technology would ‘open the door to an era of high-tech consumer eugenics’, with affluent parents choosing the best qualities and creating a new form of

genetically modified

human. To these scientists, the complex issue boils down to a simple point: ‘We must not engineer the genes we pass on to our descendants.’

Such concerns cannot be heard from the British government, which recently helped to build the Francis Crick Institute, a new nerve centre for biomedical research. A few weeks ago, the institute was given authorisation to begin a new, controversial gene-editing technique known as

CRISPR-Cas9. To supporters, this is proof of Britain’s position at the cutting edge of research. To critics, it is proof that Britain (one of the few countries that does not ban the use of fertilised human embryos in experiments) is again rushing headlong into eugenic science with minimal debate.

On the rare occasions the matter is raised in Parliament, ministers say that they do not support eugenics. But, as Chris Patten has pointed out in the Lords, that is a meaningless statement if there is no attempt to define the term. To David Galton, who has written more about the subject than any British academic, the definition is simple. If you use science to make the best of genes handed down to the next generation, that’s eugenics: ‘Sweeping the word under the carpet or sanitising it with another name merely conceals the appalling abuses that have occurred in the past and may lull people into a false sense of security.’

The idea of consumer eugenics is no futurist fantasy. Already, sperm banks boast about screening for everything from autism to red hair. £12,000 buys you the chance to choose which embryo to implant. And £400 buys sperm-sorting, the better to conceive a boy (or a girl). And even in the slums of

India, women desperate for a boy will pay for ante-natal screening to identify — and abort — girls. It doesn’t take government to pursue eugenics: parents will do it themselves.

The Francis Crick Institute says its gene-editing research has nothing to do with eugenics; even British law prohibits pregnancies from gene-edited embryos, and its researchers plan to destroy them after seven days. Instead, it aims to learn about the role of genes in miscarriage. But if its research improves gene-editing technology, less scrupulous scientists can make use of that. This is why scholars like Robert Pollack, a professor at Columbia University, want a moratorium on of germ-line

DNA modification. ‘Imagine that, many years hence, there are two sorts of people: those who carry the messy inheritance of their ancestors, and those whose ancestors had the resources to clean up their germ cells before IVF.’ So you end up with two types of humans: the genetically tidy rich and everyone else.

The experiments being carried out in London are worrying, he says, precisely because the British have such a good success rate. ‘It is not failure, but success, that concerns me,’ says Professor Pollack. ‘And for that concern, there are few venues more troubling than the Crick Institute — it is as likely as any place in the world to do this without making any distracting, avoidable mistakes.’

So some 130 years after Britain gave the world the idea of perfecting humanity, we are once again at the cutting edge of this troubled science. For good or ill, eugenics is back.

DAILY MAIL

23 JUNE 2017

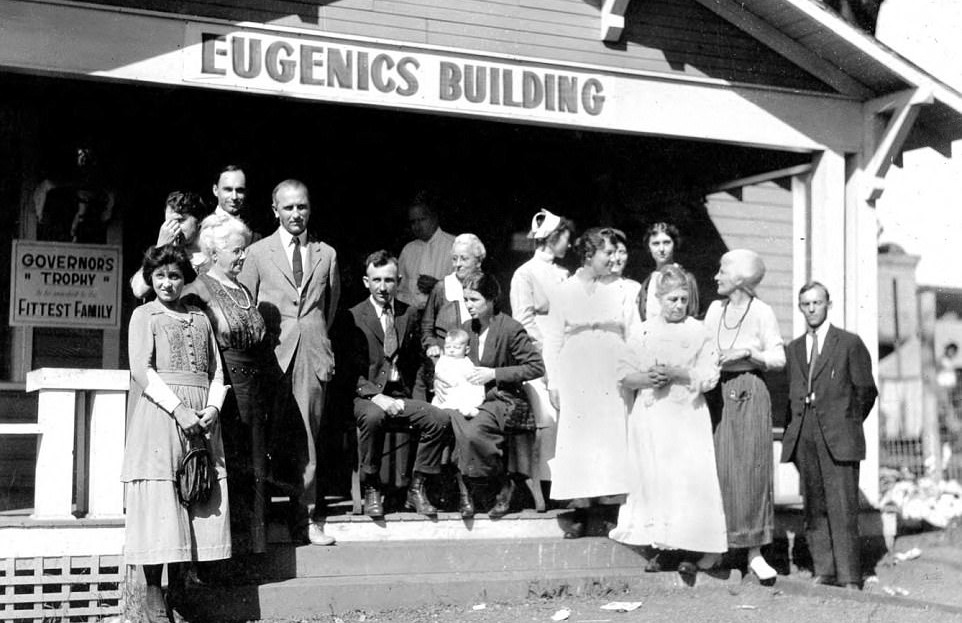

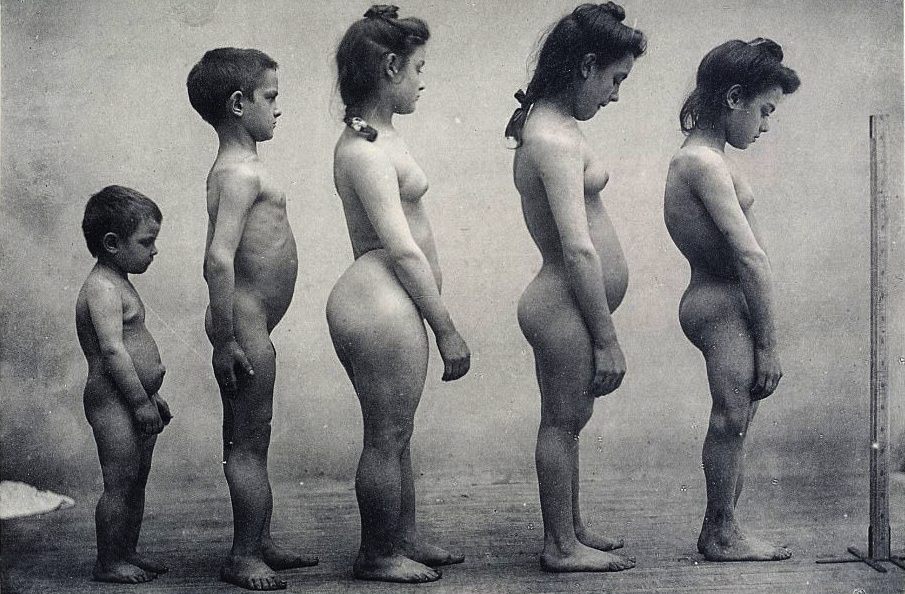

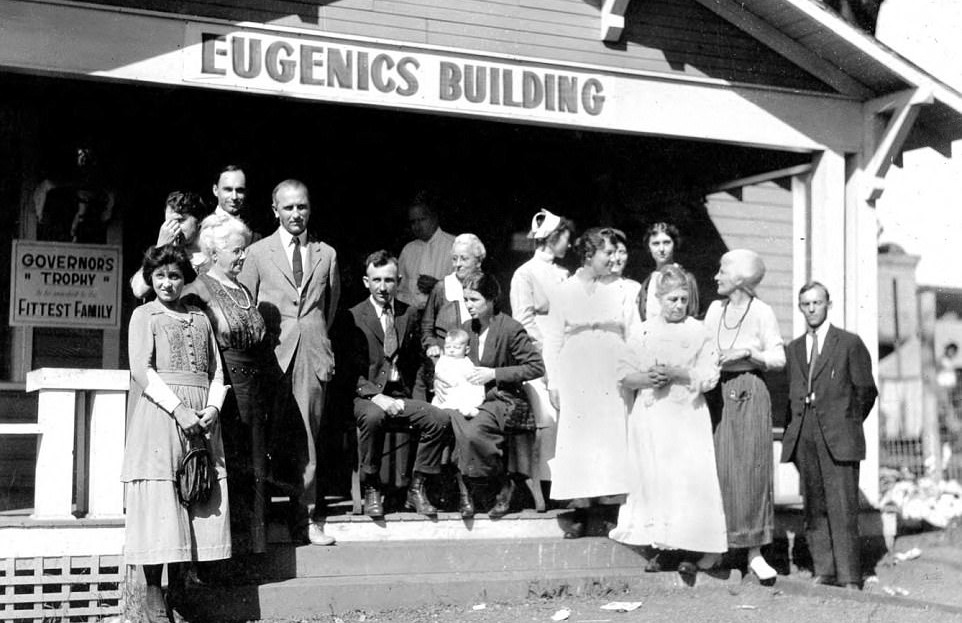

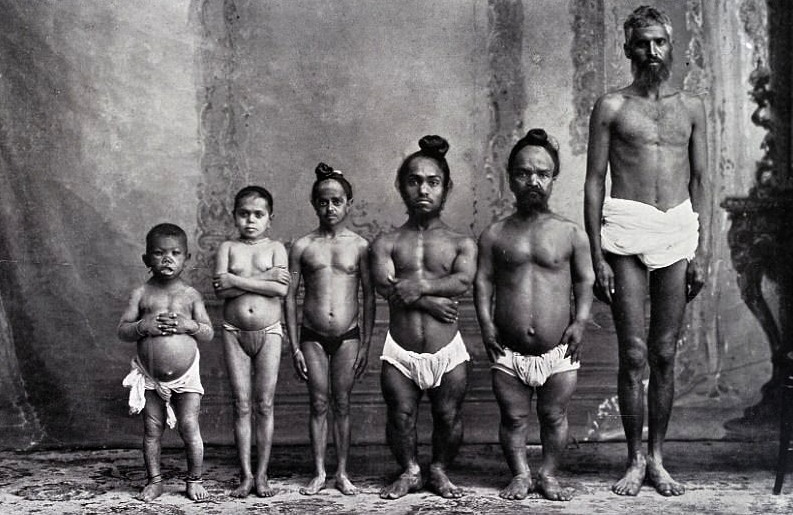

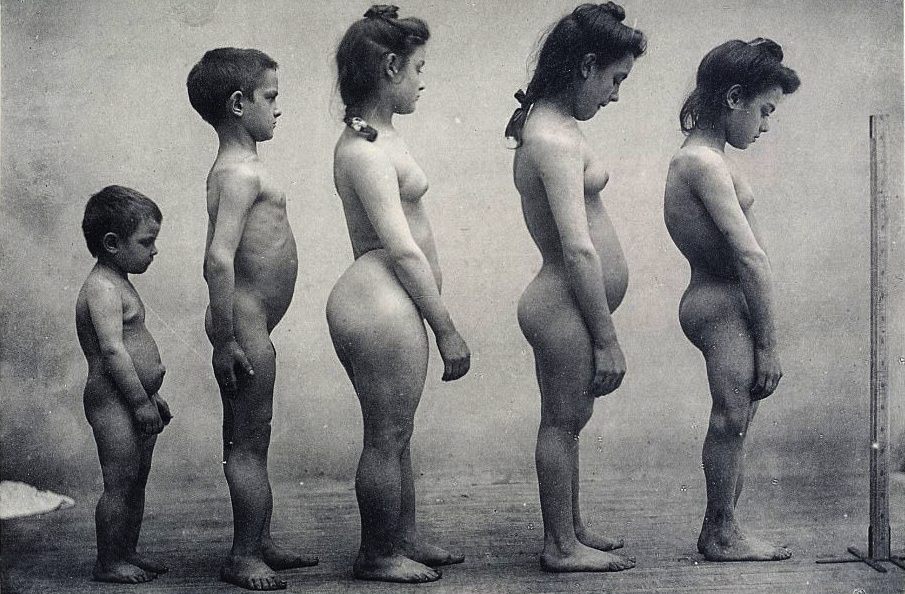

These are the horrifying photos from the heyday of the Eugenics movement that the world wants to forget.

Before the atrocities of Nazi

Germany, eugenics - the system of measuring human traits, seeking out the desirable ones and cutting out the undesirable ones - was once practised the world over.

In the decades following the 1859 publication of Charles Darwin's 'On the

Origin of

Species', a veritable craze for eugenics spread through Britain, the

United States and Europe.

These images have been released today from the the Library of Congress archive.

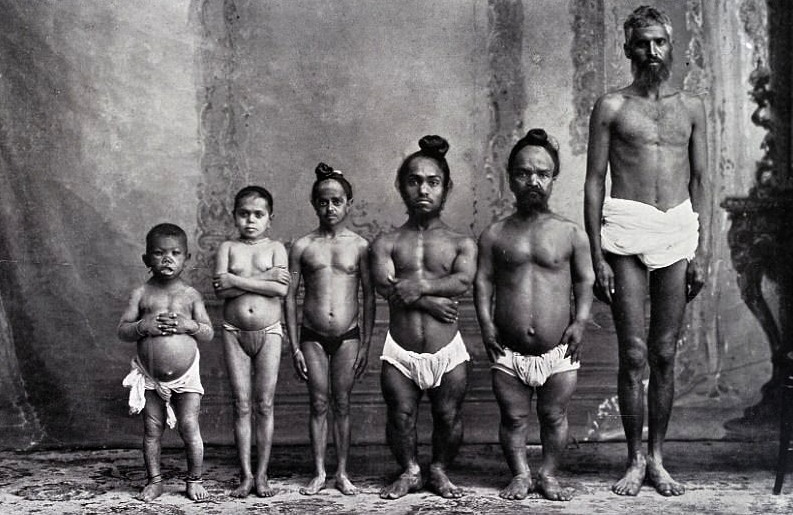

Advocates of eugenics made significant advances during the early twentieth century - and claimed that 'undesirable' genetic traits such as dwarfism, deafness and even minor defects like a cleft palate needed to be wiped out of the gene pool.

Scientists would measure the human skulls of felons in an effort to eradicate criminality - whilst other eugenic proponents suggested simply cutting out entire groups of people because of the colour of their skin.

The first sterilisation law - which stopped certain categories of disabled people from having children - was passed in Indiana, USA in 1907. This was twenty-six years before a similar law was introduced by the Nazis in Germany in 1933.

In fact, in their sterilisation propaganda, the Nazis pointed to the precedent set by America.

In one haunting image from 1912, a British family of children born with rickets is photographed by the Eugenics Society to demonstrate that their condition is hereditary and could be controlled through selective breeding.

Whilst in another photo, families from Kansas are seen competing in the 1925 'Fitter Family' contest, which was meant to find the most eugenically perfect family in America.

In another 1912 image, a child with a cleft lip poses for the camera in London, England - to show that they should be kept from breeding.

British, Sir Francis Galton - a cousin of Charles Darwin -

became obsessed with Origin of Species and coined the term 'Eugenics' in 1883. He believed that breeding humans with

superior mental and physical traits was essential to the well-being of society as a whole, writing 'Eugenics is the science which deals with all influences which improve the inborn qualities of a race; also with those which develop them to the utmost advantage.'

Galton was knighted for his scientific contributions and his writings played a key role in launching the eugenics movement in the UK and America.

In 1907, the Eugenics Education Society was founded in Britain to campaign for sterilisation and marriage restrictions for the weak to prevent the degeneration of Britain's population. A year later, Sir James Crichton-Brown, giving evidence before the 1908 Royal Commission on the Care and Control of the Feeble-Minded, recommended the compulsory sterilisation of those with learning disabilities and mental illness - an act that

Sir Winston Churchill supported.

Then in 1931, Labour MP Archibald Church proposed a bill for the compulsory sterilisation of certain categories of 'mental patient' in Parliament. Although such legislation was never actually passed in Britain, this did not prevent many sterilisations being carried out under various forms of coercion.

Meanwhile from 1907 in the United States, men, women and children who were deemed 'insane, idiotic, imbecile, feebleminded or epileptic' were forcibly sterilised, often without being informed of what was being done to them.

By 1938, 33 American states permitted the forced sterilisation of women with learning disabilities and 29 American states had passed compulsory sterilisation laws covering people who were thought to have genetic conditions. Laws in America also restricted the right of certain disabled people to marry.

Sometimes, however, things went even further. A mental institution in Illinois euthanized its patients by deliberately infecting them with tuberculosis, an act they justified as a mercy killing that cut the weak link in the human race.

Other countries which passed similar sterilisation laws in the 1920s and 30s included Sweden, Denmark, Norway and Finland.

After these kinds of ideas took root in Nazi Germany and sparked the horrors of

the Holocaust, eugenics turned into a dirty word.

With the dark conclusion of its philosophy exposed before the world, it became difficult to justify forced sterilization as a tool for the greater good.

All legislation was eventually repealed in the 1940s - and history was then subtly rewritten, with eugenics discussed as something that the Germans did and from which the rest of the world could wash its hands clean.

But, as the photos on this page make clear, for nearly 100 years, eugenics was much more than a

German idea. The whole world was complicit.

BUCHENWALD

- concentration camp (German: Konzentrationslager

(KZ) Buchenwald, in English: beech forest) was a German Nazi concentration camp established on Ettersberg hill near Weimar, Germany, in July 1937, one of the first and the largest of the concentration camps on German soil, following Dachau's opening just over four years earlier.

Prisoners from all over Europe and the Soviet Union—Jews, Poles and other Slavs, the mentally ill and physically-disabled from birth defects, religious and political prisoners, Roma and

Sinti, Freemasons, Jehovah's Witnesses (then called Bible Students), criminals, homosexuals, and prisoners of war—worked primarily as forced labor in local armaments factories. From 1945 to 1950, the camp was used by the Soviet occupation authorities as an internment camp, known as NKVD special camp number 2.

Today the remains of Buchenwald serve as a memorial and permanent exhibition and

museum.

|

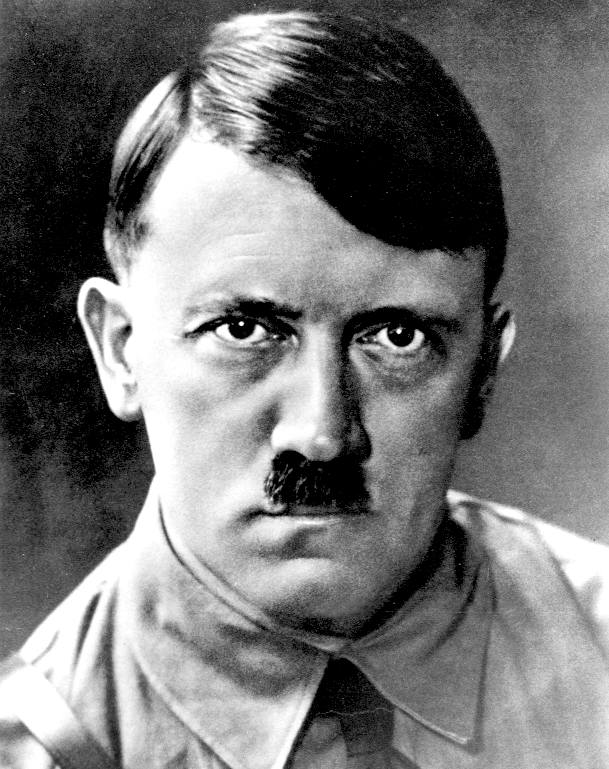

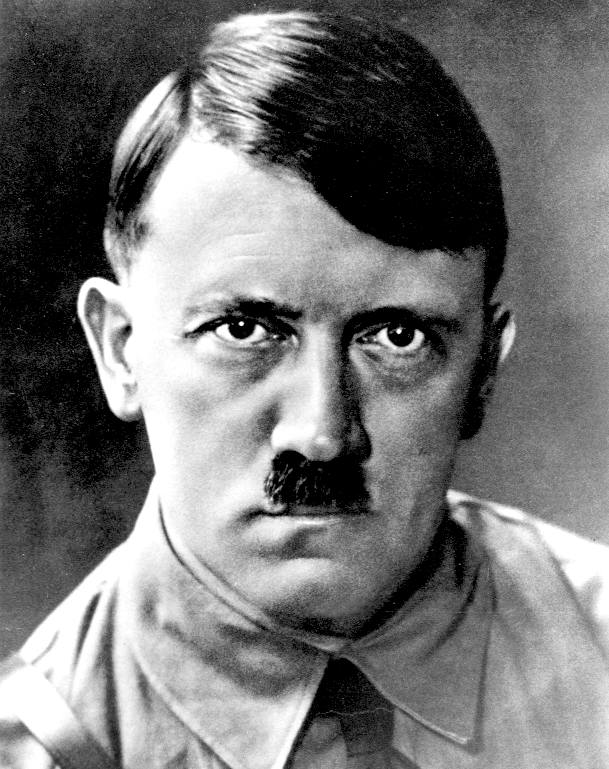

Adolf

Hitler

German

Chancellor

|

Herman

Goring

Reichsmarschall

Luftwaffe

|

Heinrich

Himmler

Reichsführer Schutzstaffel

|

Joseph

Goebbels

Reich Minister Propaganda

|

|

Philipp

Bouhler SS

NSDAP

Aktion T4

|

Dr

Josef Mengele

Physician

Auschwitz

|

Martin

Borman

Schutzstaffel

|

Adolph

Eichmann

Holocaust

Architect

|

|

Erwin

Rommel

The

Desert Fox

|

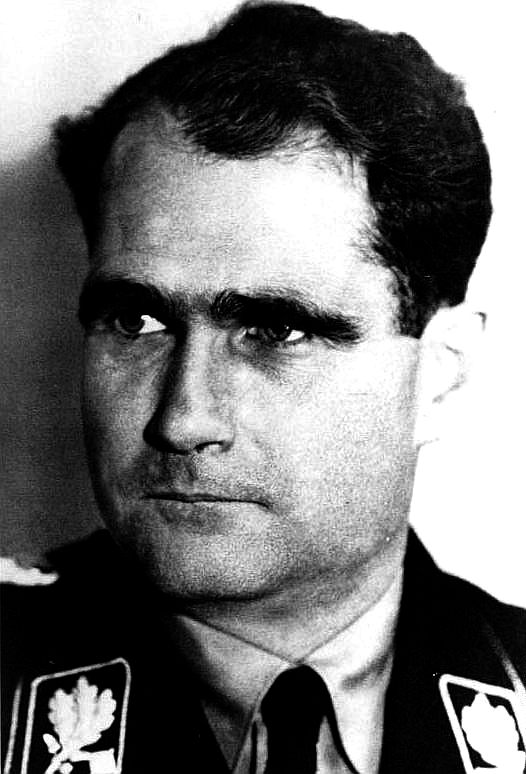

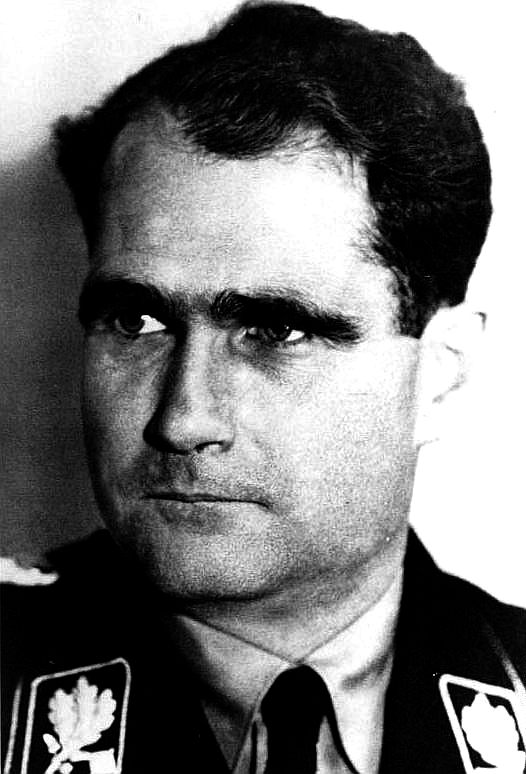

Rudolf

Hess

Auschwitz

Commandant

|

Karl

Donitz

Submarine

Commander

|

Albert

Speer

Nazi

Architect

|

A

- Z OF NAZI GERMANY

DICTIONARY.COM

noun, (used with a singular verb)

1. the study of or belief in the possibility of improving the qualities of the human species or a human population, especially by such means as discouraging reproduction by persons having genetic defects or presumed to have inheritable undesirable traits (negative eugenics) or encouraging reproduction by persons presumed to have inheritable desirable traits (positive eugenics)

ENCYCLOPEDIA BRITANNICA

Eugenics - genetics Written By: Philip K. Wilson

Eugenics, the selection of desired heritable characteristics in order to improve future generations, typically in reference to humans. The term eugenics was coined in 1883 by British explorer and natural scientist Francis Galton, who, influenced by

Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection, advocated a system that would allow “the more suitable races or strains of blood a better chance of prevailing speedily over the less suitable.” Social Darwinism, the popular theory in the late 19th century that life for humans in society was ruled by “survival of the fittest,” helped advance eugenics into serious scientific study in the early 1900s. By World War I, many scientific authorities and political leaders supported eugenics. However, it ultimately failed as a science in the 1930s and ’40s, when the assumptions of eugenicists became heavily criticized and the Nazis used eugenics to support the extermination of entire races.

Good,

bad & evil A-Z

of humanity HOME

|