|

Karl

Donitz

Karl Dönitz (sometimes spelled Doenitz) 16 September 1891 – 24 December 1980, was a German admiral who played a major role in the naval history of

World War

II. Dönitz briefly succeeded Adolf Hitler as the head of state of Germany.

He began his career in the Imperial German Navy before World War

I. In 1918, while he was in command of UB-68, the submarine was sunk by British forces and Dönitz was taken prisoner. While in a prisoner of war camp, he formulated what he later called Rudeltaktik ("pack tactic", commonly called "wolfpack"). At the start of World War II, he was the senior

submarine officer in the Kriegsmarine. In January 1943, Dönitz achieved the rank of Großadmiral (grand admiral) and replaced Grand Admiral Erich Raeder as Commander-in-Chief of the Navy.

On 30 April 1945, after the death of Adolf Hitler and in accordance with Hitler's last will and testament, Dönitz was named Hitler's successor as head of state, with the title of President of Germany and Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces. On 7 May 1945, he ordered Alfred Jodl, Chief of Operations Staff of the OKW, to sign the

German instruments of surrender in Reims,

France. Dönitz remained as head of the Flensburg Government, as it became known, until it was dissolved by the Allied powers on 23 May. At the

Nuremberg trials, he was convicted of war crimes and sentenced to ten years' imprisonment; after his release, he lived quietly in a village near Hamburg until his death in 1980.

In

this fictional John

Storm adventure,

Admiral Donitz was part of Adolf Hitler's 'Inner Circle of Six.' As such

he arranged for some of the important Nazi scientists to be

transported to South America in U-boats,

known as Operation Neuwelt.

By the start of the Second World War, Dönitz was supreme commander of the Kriegsmarine's U-boat arm (Befehlshaber der Unterseeboote (BdU)). In January 1943, Dönitz achieved the rank of Großadmiral (grand admiral) and replaced Grand Admiral Erich Raeder as Commander-in-Chief of the Navy. Dönitz was the main enemy of Allied naval forces in the Battle of the Atlantic. From 1939 to 1943 the U-boats fought effectively but lost the initiative from May 1943. Dönitz ordered his submarines into battle until 1945 to relieve the pressure on other branches of the Wehrmacht (armed forces). 648 U-boats were lost - 429 with no survivors. Furthermore, of these, 215 were lost on their first patrol. Around 30,000 of the 40,000 men who served in U-boats perished.

On 30 April 1945, after the suicide of Adolf Hitler and in accordance with his last will and testament, Dönitz was named Hitler's successor as head of state, with the title of President of Germany and Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces. On 7 May 1945, he ordered Alfred Jodl, Chief of Operations Staff of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW), to sign the German instruments of surrender in Reims, France. Dönitz remained as head of the Flensburg Government, as it became known, until it was dissolved by the Allied powers on 23 May.

By his own admission, Dönitz was a dedicated Nazi and supporter of Hitler. Following the war, he was indicted as a major war criminal at the Nuremberg trials on three counts: conspiracy to commit crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity; planning, initiating, and waging wars of aggression; and crimes against the laws of war. He was found not guilty of committing crimes against humanity, but guilty of committing crimes against peace and war crimes against the laws of war. He was sentenced to ten years' imprisonment; after his release, he lived in a village near Hamburg until his death in 1980, after a prolonged illness.

START

OF THE WAR

On 1 September 1939, Germany invaded Poland. Britain and France soon declared war on Germany, and World War II began. On Sunday 3 September, Dönitz chaired a conference at Wilhelmshaven. At 11:15 am the British Admiralty sent out a signal "Total Germany". B-Dienst intercepted the message and it was promptly reported to Dönitz. Dönitz paced around the room and his staff purportedly heard him repeatedly say, "My God! So it's war with England again!"

Dönitz abandoned the conference to return within the hour a far more composed man. He announced to his officers, "we know our enemy. We have today the weapon and a leadership that can face up to this enemy. The war will last a long time; but if each does his duty we will

win." Dönitz had only 57 boats; of those, 27 were capable of reaching the Atlantic Ocean from their German bases. A small building program was already under way but the number of U-boats did not rise noticeably until the autumn of 1941.

Dönitz's first major action was the cover up of the sinking of the British passenger liner Athenia later the same day. Acutely sensitive to international opinion and relations with the United States, the death of more than a hundred civilians was damaging. Dönitz suppressed the truth that the ship was sunk by a German submarine. He accepted the commander's explanation that he genuinely believed the ship was armed. Dönitz ordered the engagement to be struck from the submarine's logbook. Dönitz did not admit the cover up until 1946.

Hitler's original orders to wage war only in accordance with the Prize Regulations, were not issued in any altruistic spirit but in the belief hostilities with the Western Allies would be brief. On 23 September 1939, Hitler, on the recommendation of Admiral Raeder, approved that all merchant ships making use of their wireless on being stopped by U-boats should be sunk or captured. This German order marked a considerable step towards unrestricted warfare. Four days later enforcement of Prize Regulations in the North Sea was withdrawn; and on 2 October complete freedom was given to attack darkened ships encountered off the British and French coasts. Two days later the Prize Regulations were cancelled in waters extending as far as 15° West, and on 17 October the German Naval Staff gave U-boats permission to attack without warning all ships identified as hostile. The zone where darkened ships could be attacked with complete freedom was extended to 20° West on 19 October. Practically the only restrictions now placed on U-boats concerned attacks on passenger liners and, on 17 November, they too were allowed to be attacked without warning if clearly identifiable as hostile.

Although the phrase was not used, by November 1939 the BdU was practicing unrestricted submarine warfare. Neutral shipping was warned by the Germans against entering the zone which, by American neutrality legislation, was forbidden to American shipping, and against steaming without lights, zigzagging or taking any defensive precautions. The complete practice of unrestricted warfare was not enforced for fear of antagonising neutral powers, particularly the Americans. Admirals Raeder and Dönitz and the German Naval Staff had always wished and intended to introduce unrestricted warfare as rapidly as Hitler could be persuaded to accept the possible consequences.

Dönitz and Raeder accepted the death of the Z Plan upon the outbreak of war. The U-boat programme would be the only portion of it to survive 1939. Both men lobbied Hitler to increase the planned production of submarines to at least 29 per month. The immediate obstacle to the proposals was Hermann Göring, head of the Four Year Plan, commander-in-chief of the Luftwaffe and future successor to Hitler. Göring would not acquiesce and in March 1940 Raeder was forced to drop the figure from 29 to 25, but even that plan proved illusory. In the first half of 1940, two boats were delivered, increased to six in the final half of the year. In 1941 the deliveries increased to 13 to June, and then 20 to December. It was not until late 1941 the number of vessels began to increase quickly. From September 1939 through to March 1940, 15 U-boats were lost

- nine to convoy escorts. The impressive tonnage sunk had little impact on the Allied war effort at that point.

SUBMARINE FLEET COMMANDER

On 1 October 1939, Dönitz became a Konteradmiral (rear admiral) and "Commander of the Submarines" (Befehlshaber der Unterseeboote, BdU). For the first part of the war, despite disagreements with Raeder where best to deploy his men, Dönitz was given considerable operational freedom for his junior rank.

From September–December 1939 U-boats sank 221 ships for 755,237 gross tons, at the cost of nine U-boats. Only 47 merchant ships were sunk in the North Atlantic, a tonnage of 249,195. Dönitz had difficulty in organising Wolfpack operations in 1939. A number of his submarines were lost en route to the Atlantic, through either the North Sea or the heavily defended English Channel. Torpedo failures plagued commanders during convoy attacks. Along with successes against single ships, Dönitz authorised the abandonment of pack attacks in the autumn. The Norwegian Campaign amplified the defects. Dönitz wrote in May 1940, "I doubt whether men have ever had to rely on such a useless weapon." He ordered the removal of magnetic pistols in favour of contact fuses and their faulty depth control systems. In no fewer than 40 attacks on Allied warships, not a single sinking was achieved. The statistics show that from the outbreak of war to approximately the spring, 1940, faulty German torpedoes saved 50–60 ships equating to 300,000 GRT.

Dönitz was encouraged in operations against warships by the sinking of the aircraft carrier Courageous. On 28 September 1939 he said, "it is not true Britain possesses the means to eliminate the U-boat menace." The first specific operation—named "Special Operation P"—authorised by Dönitz was Günther Prien's attack on Scapa Flow, which sank the battleship Royal Oak. The attack became a propaganda success though Prien purportedly was unenthusiastic about being used that way. Stephen Roskill wrote, "It is now known that this operation was planned with great care by Admiral Dönitz, who was correctly informed of the weak state of the defences of the eastern entrances. Full credit must also be given to Lieutenant Prien for the nerve and determination with which he put Dönitz's plan into execution."

In May 1940, 101 ships were sunk - but only nine in the Atlantic

- followed by 140 in June; 53 of them in the Atlantic for a total of 585,496 GRT that month. The first six months in 1940 cost Dönitz 15 U-boats. Until mid-1940 there remained a chronic problem with the reliability of the G7e torpedo. As the battles of Norway and Western Europe raged, the Luftwaffe sank more ships than the U-boats. In May 1940, German aircraft sank 48 ships (158 GRT), three times that of German submarines. The Allied evacuations from western Europe and Scandinavia in June 1940 attracted Allied warships in large numbers, leaving many of the Atlantic convoys travelling through the Western Approaches unprotected. From June 1940, the German submarines began to exact a heavy toll. In the same month, the Luftwaffe sank just 22 ships (195,193 GRT) in a reversal of the previous months.

Germany's defeat of Norway gave the U-boats new bases much nearer to their main area of operations off the Western Approaches. The U-boats operated in groups or 'wolf packs' which were coordinated by radio from land. With the fall of France, Germany acquired U-boat bases at Lorient, Brest, St Nazaire, and La Pallice/La Rochelle and Bordeaux. This extended the range of Type VIIs. Regardless, the war with Britain continued. The admiral remained sceptical of Operation Sea Lion, a planned invasion and expected a long war. The destruction of seaborne trade became German strategy against Britain after the defeat of the Luftwaffe in the Battle of Britain. Hitler was content with The Blitz and cutting off Britain's imports. Dönitz gained importance as the prospect of a quick victory faded. Dönitz concentrated groups of U-boats against the convoys and had them attack on the surface at night. In addition the Germans were helped by Italian submarines which in early 1941 actually surpassed the number of German U-boats. Having failed to persuade the Nazi leadership to prioritise U-boat construction, a task made more difficult by military victories in 1940 which convinced many people that Britain would give up the struggle, Dönitz welcomed the deployment of 26 Italian submarines to his force. Dönitz complimented Italian bravery and daring, but was critical of their training and submarine designs. Dönitz remarked they lacked the necessary toughness and discipline and consequently were "of no great assistance to us in the Atlantic."

The establishment of German bases on the French Atlantic coast allowed for the prospect of aerial support. Small numbers of German aircraft, such as the long-range Focke-Wulf Fw 200, sank a large number of ships in the Atlantic in the last quarter of 1940. In the long term, Göring proved an insurmountable problem in effecting cooperation between the navy and the Luftwaffe. In early 1941, while Göring was on leave, Dönitz approached Hitler and secured from him a single bomber/maritime patrol unit for the navy. Göring succeeded in overturning this decision and both Dönitz and Raeder were forced to settle for a specialist maritime air command under Luftwaffe control. Poorly supplied, Fliegerführer Atlantik achieved modest success in 1941, but thereafter failed to have an impact as British counter-measures evolved. Cooperation between the Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe remained dysfunctional to the war's end. Göring and his unassailable position at the Reichsluftfahrtministerium (Air Ministry) prevented all but limited collaboration.

The U-boat fleet's successes in 1940 and early 1941 were spearheaded by a small number of highly trained and experienced pre-war commanders. Otto Kretschmer, Joachim Schepke, and Günther Prien were the most famous, but others included Hans Jenisch, Victor Oehrn, Engelbert Endrass, Herbert Schultze and Hans-Rudolf Rösing. Although skilled and with impeccable judgement, the shipping lanes they descended upon were poorly defended. The U-boat force did not escape unscathed. Within the space of several days in March 1941, Prien and Schepke were dead and Kretschmer was a prisoner. All of them fell in battle with a convoy system. The number of boats in the Atlantic remained low. Six fewer existed in May 1940 than in September 1939. In January 1941 there were just six on station in the

Atlantic - the lowest during the war, while still suffering from unreliable torpedoes. Dönitz insisted that operations continue while "the smallest prospect of hits" remained.

For his part, Dönitz was involved in the daily operations of his boats and all the major operational level decisions. His assistant, Eberhard Godt, was left to manage daily operations as the war continued. Dönitz was debriefed personally by his captains which helped establish a rapport between leader and led. Dönitz neglected nothing that would make the bond firmer. Often there would be a distribution of medals or awards. As an ex-submariner, Dönitz did not like to contemplate the thought of a man who had done well heading out to sea, perhaps never to return, without being rewarded or receiving recognition. Dönitz acknowledged where decorations were concerned there was no red tape and that awards were "psychologically important."

ENIGMA INTELLIGENCE BATTLE

Intelligence played an important role in the Battle of the Atlantic. In general, BdU intelligence was poor. Counter-intelligence was not much better. At the height of the battle in mid-1943 some 2,000 signals were sent from the 110 U-boats at sea. Radio traffic compromised his ciphers by giving the Allies more messages to work with. Furthermore, replies from the boats enabled the Allies to use High-frequency direction finding (HF/DF, called "Huff-Duff") to locate a U-boat using its radio, track it and attack it. The over-centralised command structure of BdU and its insistence on micro-managing every aspect of U-boat operations with endless signals provided the Allied navies with enormous intelligence. The enormous "paper chase" [cross-referencing of materials] operations pursued by Allied intelligence agencies was not thought possible by

BdU.

The Germans did not suspect the Allies had identified the codes broken by B-Dienst. Conversely, when Dönitz suspected the enemy had penetrated his own communications BdU's response was to suspect internal sabotage and reduce the number of the staff officers to the most reliable, exacerbating the problem of over-centralisation. In contrast to the Allies, the Wehrmacht was suspicious of civilian scientific advisors and generally distrusted outsiders. The Germans were never as open to new ideas or thinking of war in intelligence terms. According to one analyst BdU "lacked imagination and intellectual daring" in the naval war. These Allied advantages failed to avert heavy losses in the June 1940 – May 1941 period, known to U-boat crews as the "First Happy Time." In June 1941, 68 ships were sunk in the North Atlantic (318,740 GRT) at a cost of four U-boats, but the German submarines would not eclipse that number for the remainder of the year. Just 10 transports were sunk in November and December 1941.

On 7 May 1941, the Royal Navy captured the German Arctic meteorological vessel München and took its Enigma machine intact, this allowed the Royal Navy to decode U-boat radio communications in June 1941. Two days later the capture of U-110 was an intelligence coup for the British. The settings for high-level "officer-only" signals, "short-signals" (Kurzsignale) and codes standardising messages to defeat HF/DF fixes by sheer speed were found. Only the Hydra settings for May were missing. The papers were the only stores destroyed by the crew. The capture on 28 June of another weather ship, Lauenburg, enabled British decryption operations to read radio traffic in July 1941. Beginning in August 1941, Bletchley Park operatives could decrypt signals between Dönitz and his U-boats at sea without any restriction.

The capture of the U-110 allowed the Admiralty to identify individual boats, their commanders, operational readiness, damage reports, location, type, speed, endurance from working up in the Baltic to Atlantic patrols. On 1 February 1942, the Germans had introduced the M4 cipher machine, which secured communications until it was cracked in December 1942. Even so, the U-boats achieved their best success against the convoys in March 1943, due to an increase in U-boat numbers, and the protection of the shipping lines was in jeopardy. Due to the cracked M4 and the use of radar, the Allies began to send air and surface reinforcements to convoys under threat. The shipping lines were secured, which came as a great surprise to Dönitz. The lack of intelligence and increased numbers of

U-boats contributed enormously to Allied losses that year.

Signals security aroused Dönitz's suspicions during the war. On 12 January 1942 German supply submarine U-459 arrived 800 nautical miles west of Freetown, well clear of convoy lanes. It was scheduled to rendezvous with an Italian submarine, until intercepted by a warship. The German captain's report coincided with reports of a decrease in sightings and a period of tension between Dönitz and Raeder.

The number of U-boats in the Atlantic, by logic, should have increased, not lowered the number of sightings and the reasons for this made Dönitz uneasy. Despite several investigations, the conclusion of the BdU staff was that Enigma was impenetrable. His signals officer responded to the U-459 incident with answers ranging from coincidence, direction finding to Italian treachery. General Erich Fellgiebel, Chief Signal Officer of Army High Command and of Supreme Command of Armed Forces (Chef des Heeresnachrichtenwesens), apparently concurred with Dönitz. He concluded that there was "convincing evidence" that, after an "exhaustive investigation" that the Allied codebreakers had been reading high level communications. Other departments in the navy downplayed or dismissed these concerns. They vaguely implied "some components" of

Enigma had been compromised, but there was "no real basis for acute anxiety as regards any compromise of operational security."

PRESIDENT OF GERMANY

Dönitz admired Hitler and was vocal about the qualities he perceived in Hitler's leadership. In August 1943, he praised his foresightedness and confidence; "anyone who thinks he can do better than the Führer is stupid." Dönitz's relationship with Hitler strengthened through to the end of the war, particularly after the 20 July plot, for the naval staff officers were not involved; when news of it came there was indignation in the OKM. Even after the war, Dönitz said he could never have joined the conspirators. Dönitz tried to imbue Nazi ideas among his officers, though the indoctrination of the naval officer corps was not the brainchild of Dönitz, but rather a continuation of the Nazification of the navy begun under his predecessor Raeder. Naval officers were required to attend a five-day education course in Nazi ideology. Dönitz's loyalty to him and the cause was rewarded by Hitler, who, owing to Dönitz's leadership, never felt abandoned by the navy. In gratitude, Hitler appointed the navy's commander as his successor before he committed suicide.

Dönitz's influence on military matters was also evident. Hitler acted on Dönitz's advice in September 1944 to block the Gulf of Finland after Finland abandoned the Axis powers. Operation Tanne Ost was a poorly executed disaster. Dönitz shared Hitler's senseless strategic judgement

- with the Courland Pocket on the verge of collapse, and the air and army forces requesting a withdrawal, the two men were preoccupied in planning an attack on an isolated island in the far north. Hitler's willingness to listen to the naval commander was based on his high opinion of the navy's usefulness at this time. It reinforced isolated coastal garrisons along the Baltic and evacuated thousands of German soldiers and civilians in order that they might continue to participate in the war effort into the spring of 1945.

In the final days of the war, after Hitler had taken refuge in the Führerbunker beneath the Reich Chancellery garden in Berlin, Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring was considered the obvious successor to Hitler, followed by Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler. Göring, however, infuriated Hitler by radioing him in Berlin asking for permission to assume leadership of the Reich. Himmler also tried to seize power by entering into negotiations with Count Bernadotte. On 28 April 1945, the BBC reported Himmler had offered surrender to the western Allies and that the offer had been declined.

From mid-April 1945, Dönitz and elements of what remained of the Reich government moved into the buildings of the Stadtheide Barracks in Plön. In his last will and testament, dated 29 April 1945, Hitler named Dönitz his successor as Staatsoberhaupt (Head of State), with the titles of Reichspräsident (President) and Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces. The same document named Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels as Head of Government with the title of Reichskanzler (Chancellor). Hitler would not name any successors to hold his titles of Führer or leader of the Nazi Party. Furthermore, Hitler declared both Göring and Himmler traitors and expelled them from the party. He committed suicide on 30 April.

On 1 May, the day after Hitler's own suicide, Goebbels committed suicide. Dönitz thus became the sole representative of the collapsing German Reich. On 2 May, the new government of the Reich fled to Flensburg-Mürwik where he remained until his arrest on 23 May 1945. That night, 2 May, Dönitz made a nationwide radio address in which he announced Hitler's death and said the war would continue in the East "to save Germany from destruction by the advancing Bolshevik enemy."

Dönitz knew that Germany's position was untenable and the Wehrmacht was no longer capable of offering meaningful resistance. During his brief period in office, he devoted most of his effort to ensuring the loyalty of the German armed forces and trying to ensure German personnel would surrender to the British or Americans and not the Soviets. He feared vengeful Soviet reprisals, and hoped to strike a deal with the Western Allies. In the end, Dönitz's tactics were moderately successful, enabling about 1.8 million German soldiers to escape Soviet capture. As many as 2.2 million may have been evacuated.

Through 1944 and 1945, the Dönitz-initiated Operation Hannibal had the distinction of being the largest naval evacuation in history. The Baltic Fleet was presented with a mass of targets, the subsequent Soviet submarine Baltic Sea campaign in 1944 and Soviet naval

Baltic Sea campaign in 1945 inflicted grievous losses during Hannibal. The most notable was the sinking of the MV Wilhelm Gustloff by a Soviet submarine. The liner had nearly 10,000 people on board. The evacuations continued after the surrender. From 3 to 9 May 1945, 81,000 of the 150,000 persons waiting on the Hel Peninsula were evacuated without loss. Albrecht Brandi, commander of the eastern Baltic, initiated a counter operation, the Gulf of Finland campaign, but failed to have an impact.

FLENSBURG GOVERNMENT SURRENDERS

On 4 May, Admiral Hans-Georg von Friedeburg, representing Dönitz, surrendered all German forces in the Netherlands, Denmark, and northwestern Germany to Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery at Lüneburg Heath southeast of Hamburg, signaling the end of World War II in northwestern Europe.

A day later, Dönitz sent Friedeburg to US General Dwight D. Eisenhower's headquarters in Rheims, France, to negotiate a surrender to the Allies. The Chief of Staff of OKW, Generaloberst (Colonel-General) Alfred Jodl, arrived a day later. Dönitz had instructed them to draw out the negotiations for as long as possible so that German troops and refugees could surrender to the Western powers, but when Eisenhower let it be known he would not tolerate their stalling, Dönitz authorized Jodl to sign the instrument of unconditional surrender at 1:30 on the morning of 7 May. Just over an hour later, Jodl signed the documents. The surrender documents included the phrase, "All forces under German control to cease active operations at 23:01 hours Central European Time on 8 May 1945." At Stalin's insistence, on 8 May, shortly before midnight, (Generalfeldmarschall) Wilhelm Keitel repeated the signing in Berlin at Marshal Georgiy Zhukov's headquarters, with General Carl Spaatz of the USAAF present as Eisenhower's representative. At the time specified, World War II in Europe ended.

On 23 May, the Dönitz government was dissolved when Dönitz was arrested by an RAF Regiment task force. The Großadmiral's Kriegsmarine flag, which was removed from his headquarters, can be seen at the RAF Regiment Heritage Centre at RAF Honington. Generaloberst Jodl, Reichsminister Speer and other members were also handed over to troops of the King's Shropshire Light Infantry at Flensburg. His ceremonial baton, awarded to him by Hitler, can be seen in the regimental museum of the KSLI in Shrewsbury Castle.

NUREMBURG WAR TRIALS

Following the war, Dönitz was held as a prisoner of war by the Allies. He was indicted as a major war criminal at the Nuremberg Trials on three counts. One: conspiracy to commit crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. Two: planning, initiating, and waging wars of aggression. Three: crimes against the laws of war. Dönitz was found not guilty on count one of the indictment, but guilty on counts two and three.

During the trial, army psychologist Gustave Gilbert was allowed to examine Nazi leaders on trial for war crimes. Among other tests, a German version of the Wechsler–Bellevue IQ test was administered. Dönitz and Hermann Göring scored 138, which made them equally the third-highest among the Nazi leaders tested.

At the trial, Dönitz was charged with waging unrestricted submarine warfare against neutral shipping, permitting Hitler's Commando Order of 18 October 1942 to remain in full force when he became commander-in-chief of the Navy, and to that extent responsibility for that crime. His defence was that the order excluded men captured in naval warfare, and that the order had not been acted upon by any men under his command. Added to that was his knowledge of 12,000 involuntary foreign workers working in the shipyards, and doing nothing to stop it. Dönitz was unable to defend himself on this charge convincingly when cross-examined by prosecutor Sir David Maxwell Fyfe.

Among the war-crimes charges, Dönitz was accused of waging unrestricted submarine warfare for issuing War Order No. 154 in 1939, and another similar order after the Laconia incident in 1942, not to rescue survivors from ships attacked by submarine. By issuing these two orders, he was found guilty of causing Germany to be in breach of the Second London Naval Treaty of 1936. However, as evidence of similar conduct by the Allies was presented at his trial, his sentence was not assessed on the grounds of this breach of international law.

On the specific war crimes charge of ordering unrestricted submarine warfare, Dönitz was found "[not] guilty for his conduct of submarine warfare against British armed merchant ships", because they were often armed and equipped with radios which they used to notify the admiralty of attack. As stated by the judges:

" Dönitz is charged with waging unrestricted submarine warfare contrary to the Naval Protocol of 1936 to which Germany acceded, and which reaffirmed the rules of submarine warfare laid down in the London Naval Agreement of 1930 ... The order of Dönitz to sink neutral ships without warning when found within these zones was, therefore, in the opinion of the Tribunal, violation of the Protocol ... The orders, then, prove Dönitz is guilty of a violation of the Protocol ... The sentence of Dönitz is not assessed on the ground of his breaches of the international law of submarine warfare."

His sentence on unrestricted submarine warfare was not assessed because of similar actions by the Allies. In particular, the British Admiralty, on 8 May 1940, had ordered all vessels in the Skagerrak sunk on sight, and Admiral Chester Nimitz, wartime commander-in-chief of the US Pacific Fleet, stated the US Navy had waged unrestricted submarine warfare in the Pacific from the day the US officially entered the war. Thus, Dönitz was not charged of waging unrestricted submarine warfare against unarmed neutral shipping by ordering all ships in designated areas in international waters to be sunk without warning.

Dönitz was imprisoned for 10 years in Spandau Prison in what was then West Berlin. During his period in prison he was unrepentant, and maintained that he had done nothing wrong. He also rejected Speer's attempts to persuade him to end his devotion to Hitler and accept responsibility for the wrongs the German Government had committed. Over 100 senior Allied officers also sent letters to Dönitz conveying their disappointment over the unfairness and verdict of his trial.

A

- Z OF NAZI GERMANY

|

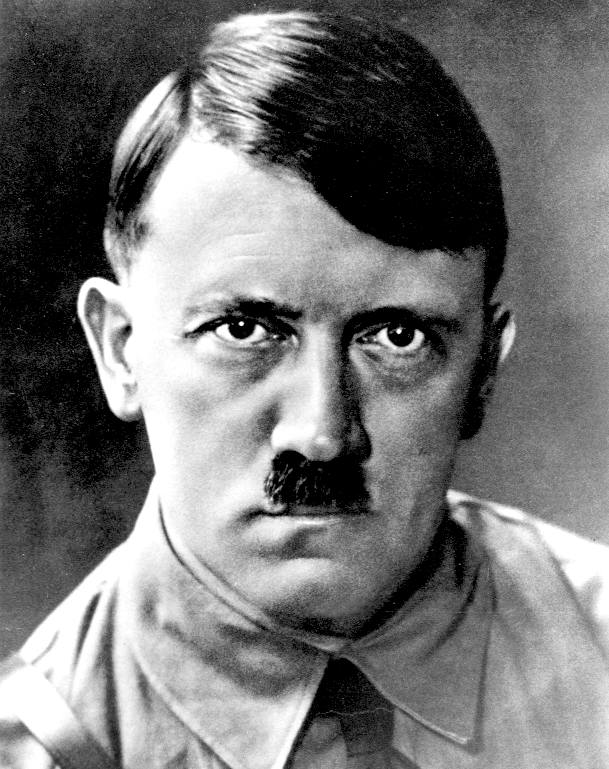

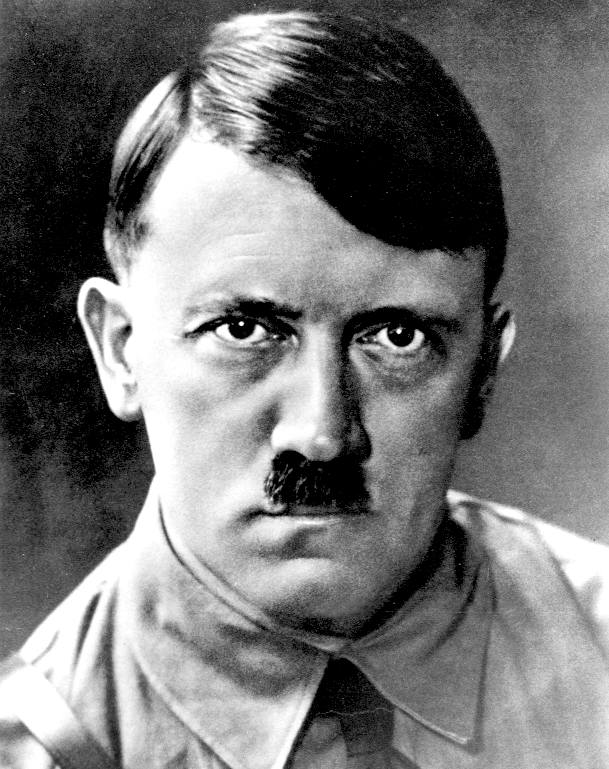

Adolf

Hitler

German

Chancellor

|

Herman

Goring

Reichsmarschall

Luftwaffe

|

Heinrich

Himmler

Reichsführer Schutzstaffel

|

Joseph

Goebbels

Reich Minister Propaganda

|

|

Philipp

Bouhler SS

NSDAP

Aktion T4

|

Dr

Josef Mengele

Physician

Auschwitz

|

Martin

Borman

Schutzstaffel

|

Adolph

Eichmann

Holocaust

Architect

|

|

Erwin

Rommel

The

Desert Fox

|

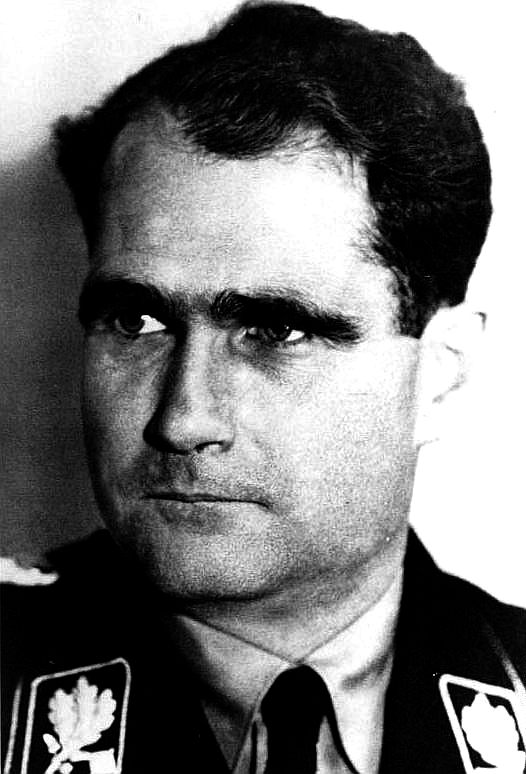

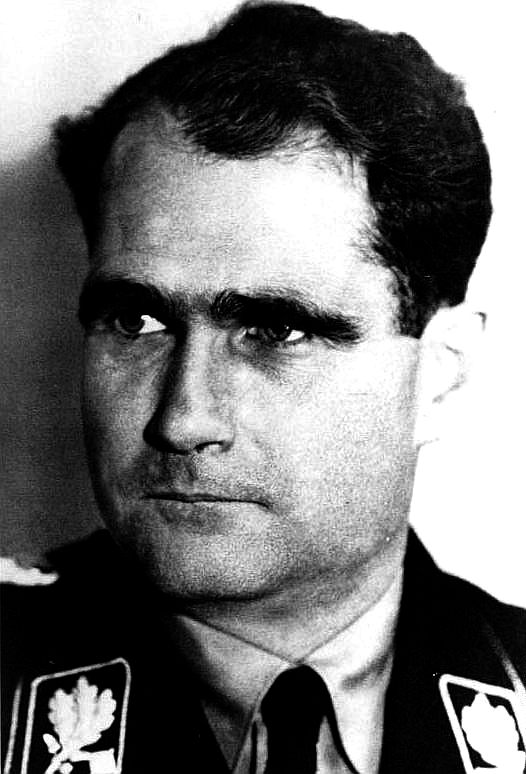

Rudolf

Hess

Auschwitz

Commandant

|

Karl

Donitz

Submarine

Commander

|

Albert

Speer

Nazi

Architect

|

Good,

bad & evil A-Z

of humanity HOME

|