|

Almost

any human cell can be used to replicate a person via cloning,

but care should be taken when matching

The replication of biological organisms, has been proven to

work very effectively. This is commonly called cloning. In

science fiction artificial humans are called replicants,

cyborgs (part machine), or skin jobs, as distinct from synthetic humans,

that are actually robots, or organic machines designed to

look and act like humans.

Robotic

science has not developed this far as yet when it comes to

humanoid form. But cloning technology is a fact of life.

Though illegal at the present time. Driving much of the

research underground.

In

order to be able to duplicate a subject, their DNA

is needed. If the DNA is is good condition, i.e., the Genome

is complete, replication is a relatively simple matter in

the right laboratory conditions.

With

the possible exception of identical twins, each person's DNA is unique. This is why people can be identified using DNA fingerprinting.

DNA can be cut up and separated, which can form a 'bar code' that is different from one person to the next.

In

the future, people might be reincarnated,

using technology that exists today that is illegal, in a

time when populations are threatened, or other reasons for

making such resurrection from storage useful - or legal.

It

would then be possible to live forever, a kind of afterlife,

dreamed of by Ancient

Egyptians, Christians (going to heaven

or hell) and many other religions. For this reason, and such

as not to dilute the religious beliefs of Catholics and

other religions based on Jesus

Christ, and the Lord

Almighty, the Church are very interested in keeping the

whereabouts of Cleopatra

a secret.

Today,

wealthy people store their bodies cryogenically for many

reasons. Sperm and Eggs are also stored cryogenically. Most of the

clients of such services, tend to overlook, or otherwise

interpret their religious beliefs differently.

In

fiction, John

Storm is an amateur anthropologist who has amassed a

huge collection of Human and other DNA, so creating a

digital Ark,

where it would be possible to re-create the life of

earth, on

other planets with suitable atmospheric and other life

support.

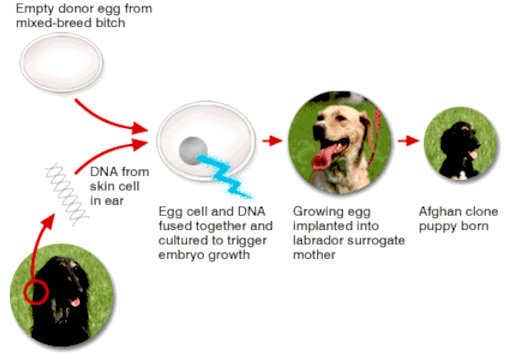

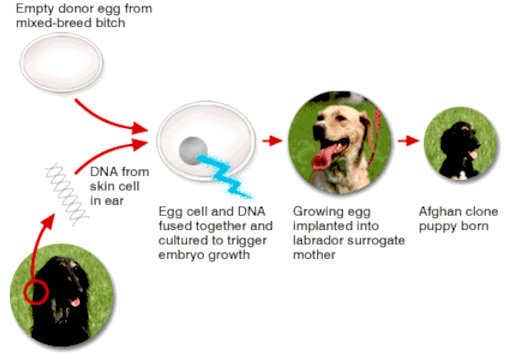

CLONING

TECHNIQUE

Cloning is a technique scientists use to make exact genetic copies of living things. Genes, cells, tissues, and even whole animals can all be cloned.

Some clones already exist in nature. Single-celled organisms like bacteria make exact copies of themselves each time they reproduce. In

humans, identical twins are similar to clones. They share almost the exact same genes. Identical twins are created when a fertilized egg splits in two.

Scientists also make clones in the lab. They often clone genes in order to study and better understand them. To clone a gene, researchers take

DNA from a living creature and insert it into a carrier like bacteria or yeast. Every time that carrier reproduces, a new copy of the gene is made.

Animals are cloned in one of two ways. The first is called embryo twinning. Scientists first split an embryo in half. Those two halves are then placed in a mother’s uterus. Each part of the embryo develops into a unique animal, and the two animals share the same genes. The second method is called somatic cell nuclear transfer. Somatic cells are all the cells that make up an organism, but that are not sperm or egg cells. Sperm and egg cells contain only one set of chromosomes, and when they join during fertilization, the mother’s chromosomes merge with the father’s.

Somatic cells, on the other hand, already contain two full sets of chromosomes. To make a clone, scientists transfer the DNA from an animal’s somatic cell into an egg cell that has had its nucleus and DNA removed. The egg develops into an embryo that contains the same genes as the cell donor. Then the embryo is implanted into an adult female’s uterus to grow.

Unless, you have one of Franco

Francisco's artificial wombs.

One

can imagine the outcry by women's rights campaigners,

imagining themselves as redundant mothers. On the other

hand, career women who cannot take time off to have a child,

might like the idea. Don't worry ladies, nothing can replace

the love and care of a real mother, whether adopting, or

giving birth to your own family members.

If

you are going to clone a human, you might as well copy

someone exceptional.

DOLLY

In 1996, Scottish scientists cloned the first animal, a sheep they named Dolly. She was cloned using an udder cell taken from an adult sheep. Since then, scientists have cloned cows, cats, deer, horses, and rabbits.

They still have not cloned a

human, though. In part, this is because it is difficult to produce a viable clone. In each attempt, there can be genetic mistakes that prevent the clone from surviving. It took scientists 276 attempts to get Dolly right. There are also ethical concerns about cloning a human being.

Researchers can use clones in many ways. An embryo made by cloning can be turned into a stem cell factory. Stem cells are an early form of cells that can grow into many different types of cells and tissues. Scientists can turn them into nerve cells to fix a damaged spinal cord or insulin-making cells to treat diabetes.

The cloning of animals has been used in a number of different applications. Animals have been cloned to have gene mutations that help scientists study diseases that develop in the animals. Livestock like cows and pigs have been cloned to produce more milk or meat. Clones can even “resurrect” a beloved pet that has died. In 2001, a cat named CC was the first pet to be created through cloning. Cloning might one day bring back extinct species like the woolly mammoth,

giant panda, or even the dinosaurs - as seen in Jurassic

Park.

APRIL

2005 - Snuppy, the first successfully cloned Afghan hound, sits with his generic father at the Seoul National University on August 3, 2005 in Seoul, South Korea. The dog joined the list of cloned animals as South Korean scientists, led by stem cell researcher Dr. Hwang Woo-Suk, announced that they have created the first cloned dog from an Afghan hound in the world.

SNUPPY

In April 2005, a dog named Snuppy was successfully cloned by Korean scientists. The male Afghan Hound named Snuppy, was born on April 24; scientists created him using a cell from the ear of an adult Afghan Hound and the procedure involved 123 surrogate mothers, of which only three produced pups and of the three puppies only Snuppy survived.

Snuppy was named as Time Magazine‘s “Most Amazing Invention” of the year in 2005. According to Wikipedia, The Kennel Club criticized the entire concept of dog cloning, on the grounds that their mission is: “To promote in every way the general improvement of dogs” and no improvement can occur if replicas are being created.

That is not true of course. With modern gene manipulation, 'improvements' can be engineered

(genetically modified) and deliberate, rather than haphazard,

as with natural selection. Thus, taking much of the

guesswork and random haziness out of the equation.

HUMAN

CLONES

Human

cloning is inevitable. It has already taken place

conceptually.

We

are not talking about the “artificial twinning” experiments performed in 1993 at the Washington University Medical

Center. Although newspapers were quick to trumpet this as human cloning, it was soon revealed that in reality this was a relatively primitive procedure in which an already-fertilized egg was split into two fertilized eggs. A nice party trick, but Mother Nature already does it thousand of times a day when she creates twins, triplets, etc.

Further proof that the concept of cloning is sound.

The real cloning took place two years later, in 1995, although it wasn’t revealed until mid-November

1998. Unbelievably, only a few small newspaper stories weakly revealed one of the most important biotechnology developments of all time. In fact, it’s probably one of the most important developments in the history of science and

technology.

Working under the auspices of the private company Advanced Cell Technology, and using the facilities of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, scientists James Robl and Jose Cibelli created a human clone. They took cells from Cibelli’s leg and cheek, put them alongside a cow’s ovum with the genetic material stripped out, and added a jolt of electricity.

One of Cibelli’s cells fused with the cow’s ovum, which acted as though it had been fertilized, and the cells began dividing. This is the same process used to create Dolly, the

cloned sheep from Scotland, only this was done before Dolly was created.

A small story in the Boston Globe reported the following about this achievement:

The experiments were privately funded, and therefore aren’t bound by government regulations on embryo research....

The researchers fused a human skin cell with a cow egg stripped of its nucleus because that avoided using a scarce human egg to nurture the genetic program of the new embryo, they

said.

So what happened to the clone?

The scientists destroyed it when it reached the 32-cell stage. In other words, the zygote had already gone through five divisions and was on its way to becoming a human being. Scientists aren’t completely certain what would’ve happened if the zygote had been allowed to develop in a womb or in vitro, since such a thing has never been attempted (as far as we know), but Dr. Patrick Dixon

had an educated guess:

If the clone had been allowed to continue beyond implantation it would have developed as Dr. Cibelli’s identical twin. Technically 1% of the human clone genes would have belonged to the

cow - the mitochondria genes.

Mitochondria are power generators in the cytoplasm of the cell. They grow and divide inside cells and are passed on from one generation to another. They are present in sperm and eggs.

Judging by the successful growth of the combined human-cow clone creation, it appears that cow mitochondria may well be compatible with human embryonic development.

NEW

SCIENTIST 26 DECEMBER 2002

The world’s first cloned baby was born on 26 December, claims the Bahamas-based cloning company Clonaid. But there has been no independent confirmation of the claim.

The girl, named Eve by the cloning team, was said to have been born by Caesarean section at 1155 EST. The birth at an undisclosed location went “very well”, said Brigitte Boisselier, president of Clonaid. The company was formed in 1997 by the Raelian cult, which believes people are clones of aliens.

“The baby is very healthy. She is doing fine,” Roisselier told a press conference in Hollywood, Florida, on Friday. The seven-pound baby is a clone of a 31-year-old American woman, whose partner is infertile, she said.

Proving that the baby is a clone of another person would be possible by showing that their DNA is identical. Genetic tests on the baby and “mother” will now be carried out and the results will be available “in eight or nine days”, Boisselier said.

She told reporters: “You can still go back to your office and treat me as a fraud. You have one week to do that.” Boisselier added that Michael Guillen, science editor at ABC News and a former Harvard University mathematician, will carry out the genetic tests.

Necessary expertise

Many scientists are sceptical of Boisselier’s claim. Alan Trounson of Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, says he does not believe the group has the necessary expertise to clone a person. “And nearly everything they have said in the past has never been confirmed by scientific investigation,” he told the Sydney Morning Herald.

Maverick fertility scientist Severino Antinori, who claimed earlier in December that the first cloned baby would be born in January 2003, is also critical. “An announcement of this type has no scientific corroboration and risks creating confusion,” he said. “We keep up our scientific work without making announcements. I don’t take part in this … race.”

Opponents of human cloning point to the high rate of miscarriages of cloned animal fetuses, and the high rate of defects in live births. Boisselier has claimed that the large number of female cult members willing to act as surrogate mothers increased their chances of success.

“Irresponsible and repugnant”

Attempting to clone humans is “irresponsible and repugnant and ignores the overwhelming scientific evidence from seven mammalian species cloned so far,” Rudolph Jaenisch, a cloning expert at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology told New Scientist previously.

In May, US-based fertility scientist Panos Zavos told the US Congress that five groups of scientists were rushing to be the first to produce the first cloned human baby.

Reproductive cloning – creating a baby rather than a cloned early embryo – is illegal in many countries. But in November, talks on a global ban were suspended, following a series of deadlocked

United Nations meetings.

DO

CLONED HUMANS THINK THE SAME AS THE ORIGINAL?

The

simple fact of replicating the biological host of a human,

does not re-create the person providing the DNA. For that to

happen, additional technology is needed. This is the

(fictional) technology that Baron

Heinrich Richthofen and his team are developing, in the

quest to fuse royal Egyptian and Aryan blood, to produce a queen

that thinks like Cleopatra,

from which sons and daughters may flow.

In

the Hollywood movie: The

Boys From Brazil, Neo-Nazis attempt to clone Adolf

Hitler, and provide the replicants with a similar

up-bringing, in the hope the duplicated human boys will grow

up to be like the German dictator.

From

our point of view, though the concept might work given an

infinite number of variables and unlimited time, there is a

more positive method of re-creating an exact copy of a

subject's brain. Which would otherwise develop according to

the environment it encounters when maturing, from the time

it is brought back to life. The Frankenstein films focus on

this aspect, when the Baron Victor, uses a damaged brain,

leading to unstable results - fiction though it may be, they

had a point.

Pets

that are cloned would not recognize their masters, they

would have to be re-trained. It would not matter for other

animals, such as dinosaurs, except that they would be

biologically programmed for life in the Jurassic period.

Hence, might not survive, or might be more prolific, such as

might be the case with seven billion humans as a vast food

resource. Anyone would have to be nuts to even consider cloning

dinosaurs, like the fictional Dr. John Hammond. All the

franchised 'Jurassic' films tell us the same thing. Don't do

it! Far less dangerous is the cloning of his supposed granddaughter,

Maisie - from his deceased daughter - by Sir Benjamin Lockwood, in the

2018 film Jurassic

World - Fallen Kingdom. All fiction of course. But,

entertaining fiction, based on cloning.

The

cloning

method Baron Richthofen and his team prefer, stands a very

good chance of success - and is far more sane than

replicating dinosaurs. If the plan to clone a long- lost

Pharaoh can ever be viewed as anything but research far removed from

a sound scientific experiment. For most of us. Ignoring for

now theology and mythology.

But

who can understand the workings of an obsessed mind. Provided

the Baron's team can find the near

intact DNA of an Egyptian pharaoh, as the starting point, he

is intent on giving it a go. Only John Storm and the crew of

the Elizabeth

Swann, might prevent something unholy taking

place. In a world besieged by corruption and aggressive

inhumanity to our fellow man, does it matter? John Storm

believes in the natural world, and not

interfering with nature, unless absolutely unavoidable.

Exceptions being for the

advancement of medicines to cure (at present) incurable

diseases. Or, for

the alleviation of suffering.

CLONING

DEFINITIONS AND APPLICATIONS - US NIH - NATIONAL LIBRARY OF

MEDICINE

WHAT IS MEANT BY REPRODUCTIVE CLONING OF ANIMALS INCLUDING HUMANS?

Reproductive cloning is defined as the deliberate production of genetically identical individuals. Each newly produced individual is a clone of the original. Monozygotic (identical) twins are natural clones. Clones contain identical sets of genetic material in the

nucleus - the compartment that contains the chromosomes - of every cell in their bodies. Thus, cells from two clones have the same DNA and the same genes in their nuclei.

All cells, including eggs, also contain some DNA in the energy-generating “factories” called mitochondria. These structures are in the cytoplasm, the region of a cell outside the nucleus. Mitochondria contain their own DNA and reproduce independently. True clones have identical DNA in both the nuclei and mitochondria, although the term clones is also used to refer to individuals that have identical nuclear DNA but different mitochondrial DNA.

HOW IS REPRODUCTIVE CLONING DONE?

Two methods are used to make live-born mammalian clones. Both require implantation of an embryo in a uterus and then a normal period of gestation and birth. However, reproductive human or animal cloning is not defined by the method used to derive the genetically identical embryos suitable for implantation. Techniques not yet developed or described here would nonetheless constitute cloning if they resulted in genetically identical individuals of which at least one were an embryo destined for implantation and birth.

The two methods used for reproductive cloning thus far are as follows:

• Cloning using somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) [1]. This procedure starts with the removal of the chromosomes from an egg to create an enucleated egg. The chromosomes are replaced with a nucleus taken from a somatic (body) cell of the individual or embryo to be cloned. This cell could be obtained directly from the individual, from cells grown in culture, or from frozen tissue. The egg is then stimulated, and in some cases it starts to divide. If that happens, a series of sequential cell divisions leads to the formation of a blastocyst, or preimplantation embryo. The blastocyst is then transferred to the uterus of an animal. The successful implantation of the blastocyst in a uterus can result in its further development, culminating sometimes in the birth of an animal. This animal will be a clone of the individual that was the donor of the nucleus. Its nuclear DNA has been inherited from only one genetic parent.

The number of times that a given individual can be cloned is limited theoretically only by the number of eggs that can be obtained to accept the somatic cell nuclei and the number of females available to receive developing embryos. If the egg used in this procedure is derived from the same individual that donates the transferred somatic nucleus, the result will be an embryo that receives all its genetic

material - nuclear and mitochondrial - from a single individual. That will also be true if the egg comes from the nucleus donor's mother, because mitochondria are inherited maternally. Multiple clones might also be produced by transferring identical nuclei to eggs from a single donor. If the somatic cell nucleus and the egg come from different individuals, they will not be identical to the nuclear donor because the clones will have somewhat different mitochondrial genes [2; 3]

• Cloning by embryo splitting. This procedure begins with in vitro fertilization (IVF): the union outside the woman's body of a sperm and an egg to generate a zygote. The zygote (from here onwards also called an embryo) divides into two and then four identical cells. At this stage, the cells can be separated and allowed to develop into separate but identical blastocysts, which can then be implanted in a uterus. The limited developmental potential of the cells means that the procedure cannot be repeated, so embryo splitting can yield only two identical mice and probably no more than four identical humans.

The DNA in embryo splitting is contributed by germ cells from two

individuals - the mother who contributed the egg and the father who contributed the sperm. Thus, the embryos, like those formed naturally or by standard IVF, have two parents. Their mitochondrial DNA is identical. Because this method of cloning is identical with the natural formation of monozygotic twins and, in rare cases, even quadruplets, it is not discussed in detail in this report.

WILL CLONES LOOK AND BEHAVE EXACTLY THE SAME?

Even if clones are genetically identical with one another, they will not be identical in physical or behavioral characteristics, because DNA is not the only determinant of these characteristics. A pair of clones will experience different environments and nutritional inputs while in the uterus, and they would be expected to be subject to different inputs from their parents, society, and life experience as they grow up. If clones derived from identical nuclear donors and identical mitocondrial donors are born at different times, as is the case when an adult is the donor of the somatic cell nucleus, the environmental and nutritional differences would be expected to be more pronounced than for monozygotic (identical) twins. And even monozygotic twins are not fully identical genetically or epigenetically because mutations, stochastic developmental variations, and varied imprinting effects (parent-specific chemical marks on the DNA) make different contributions to each twin [3; 4].

Additional differences may occur in clones that do not have identical mitochondria. Such clones arise if one individual contributes the nucleus and another the

egg - or if nuclei from a single individual are transferred to eggs from multiple donors. The differences might be expected to show up in parts of the body that have high demands for

energy - such as muscle, heart, eye, and brain—or in body systems that use mitochondrial control over cell death to determine cell numbers [5; 6].

WHAT ARE THE PURPOSES OF REPRODUCTIVE CLONING?

Cloning of livestock [1] is a means of replicating an existing favorable combination of traits, such as efficient growth and high milk production, without the genetic “lottery” and mixing that occur in sexual reproduction. It allows an animal with a particular genetic modification, such as the ability to produce a pharmaceutical in milk, to be replicated more rapidly than does natural mating [7; 8]. Moreover, a genetic modification can be made more easily in cultured cells than in an intact animal, and the modified cell nucleus can be transferred to an enucleated egg to make a clone of the required type. Mammals used in scientific experiments, such as mice, are cloned as part of research aimed at increasing our understanding of fundamental biological mechanisms.

In principle, those people who might wish to produce children through human reproductive cloning [9] include:

- Infertile couples who wish to have a child that is genetically identical with one of them, or with another nucleus donor

-

Other individuals who wish to have a child that is genetically identical with them, or with another nucleus donor

-

Parents who have lost a child and wish to have another, genetically identical child

-

People who need a transplant (for example, of cord blood) to treat their own or their child's disease and who therefore wish to collect genetically identical tissue from a cloned fetus or newborn.

Possible reasons for undertaking human reproductive cloning have been analyzed according to their degree of justification. For example, in reference 10 it is proposed that human reproductive cloning aimed at establishing a genetic link to a gametically infertile parent would be more justifiable than an attempt by a sexually fertile person aimed at choosing a specific genome.

Transplantable tissue may be available without the need for the birth of a child produced by cloning. For example, embryos produced by in vitro fertilization (IVF) can be typed for transplant suitability, and in the future stem cells produced by nuclear transplantation may allow the production of transplantable tissue.

HOW DOES REPRODUCTIVE CLONING DIFFER FROM STEM CELL RESEARCH?

The recent and current work on stem cells that is briefly summarized below and discussed more fully in a recent report from the National Academies entitled Stem Cells and the Future of Regenerative Medicine [11] is not directly related to human reproductive cloning. However, the use of a common initial

step - called either nuclear transplantation or somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT)

- has led Congress to consider bills that ban not only human reproductive cloning but also certain areas of stem cell research. Stem cells are cells that have the ability to divide repeatedly and give rise to both specialized cells and more stem cells. Some, such as some blood and brain stem cells, can be derived directly from adults [12- 19] and others can be obtained from preimplantation embryos. Stem cells derived from embryos are called embryonic stem cells (ES cells). The above-mentioned report from the National Academies provides a detailed account of the current state of stem cell research [11].

ES cells are also called pluripotent stem cells because their progeny include all cell types that can be found in a postimplantation embryo, a fetus, and a fully developed organism. They are derived from the inner cell mass of early embryos (blastocysts) [20- 23]. The cells in the inner cell mass of a given blastocyst are genetically identical, and each blastocyst yields only a single ES cell line. Stem cells are rarer [ 24] and more difficult to find in adults than in preimplantation embryos, and it has proved harder to grow some kinds of adult stem cells into cell lines after isolation [25; 26].

Production of different cells and tissues from ES cells or other stem cells is a subject of current research [11; 27- 31]. Production of whole organs other than bone marrow (to be used in bone marrow transplantation) from such cells has not yet been achieved, and its eventual success is uncertain.

Current interest in stem cells arises from their potential for the therapeutic transplantation of particular healthy cells, tissues, and organs into people suffering from a variety of diseases and debilitating disorders. Research with adult stem cells indicates that they may be useful for such purposes, including for tissues other than those from which the cells were derived [12; 14; 17; 18; 25- 27; 32- 43]. On the basis of current knowledge, it appears unlikely that adults will prove to be a sufficient source of stem cells for all kinds of tissues [11; 44- 47]. ES cell lines are of potential interest for transplantation because one cell line can multiply indefinitely and can generate not just one type of specialized cell, but many different types of specialized cells (brain, muscle, and so on) that might be needed for transplants [20; 28; 45; 48; 49]. However, much more research will be needed before the magnitude of the therapeutic potential of either adult stem cells or ES cells will be well understood.

One of the most important questions concerning the therapeutic potential of stem cells is whether the cells, tissues, and perhaps organs derived from them can be transplanted with minimal risk of transplant rejection. Ideally, adult stem cells advantageous for transplantation might be derived from patients themselves. Such cells, or tissues derived from them, would be genetically identical with the patient's own and not be rejected by the immune system. However, as previously described, the availability of sufficient adult stem cells and their potential to give rise to a full range of cell and tissue types are uncertain. Moreover, in the case of a disorder that has a genetic origin, a patient's own adult stem cells would carry the same defect and would have to be grown and genetically modified before they could be used for therapeutic transplantation.

The application of somatic cell nuclear transfer or nuclear transplantation offers an alternative route to obtaining stem cells that could be used for transplantation therapies with a minimal risk of transplant rejection. This

procedure - sometimes called therapeutic cloning, research cloning, or nonreproductive cloning, and referred to here as nuclear transplantation to produce stem

cells - would be used to generate pluripotent ES cells that are genetically identical with the cells of a transplant recipient [50]. Thus, like adult stem cells, such ES cells should ameliorate the rejection seen with unmatched transplants.

Two types of adult stem cells—stem cells in the blood forming bone marrow and skin stem

cells - are the only two stem cell therapies currently in use. But, as noted in the National Academies' report entitled Stem Cells and the Future of Regenerative Medicine, many questions remain before the potential of other adult stem cells can be accurately assessed [11]. Few studies on adult stem cells have sufficiently defined the stem cell's potential by starting from a single, isolated cell, or defined the necessary cellular environment for correct differentiation or the factors controlling the efficiency with which the cells repopulate an organ. There is a need to show that the cells derived from introduced adult stem cells are contributing directly to tissue function, and to improve the ability to maintain adult stem cells in culture without the cells differentiating. Finally, most of the studies that have garnered so much attention have used mouse rather than human adult stem cells.

ES cells are not without their own potential problems as a source of cells for transplantation. The growth of human ES cells in culture requires a “feeder” layer of mouse cells that may contain viruses, and when allowed to differentiate the ES cells can form a mixture of cell types at once. Human ES cells can form benign tumors when introduced into mice [20], although this potential seems to disappear if the cells are allowed to differentiate before introduction into a recipient [51]. Studies with mouse ES cells have shown promise for treating diabetes [30], Parkinson's disease [52], and spinal cord injury [53].

The ES cells made with nuclear transplantation would have the advantage over adult stem cells of being able to provide virtually all cell types and of being able to be maintained in culture for long periods of time. Current knowledge is, however, uncertain, and research on both adult stem cells and stem cells made with nuclear transplantation is required to understand their therapeutic potentials. (This point is stated clearly in Finding and Recommendation 2 of Stem Cells and the Future of Regenerative Medicine [11] which states, in part, that “studies of both embryonic and adult human stem cells will be required to most efficiently advance the scientific and therapeutic potential of regenerative medicine.”) It is likely that the ES cells will initially be used to generate single cell types for transplantation, such as nerve cells or muscle cells. In the future, because of their ability to give rise to many cell types, they might be used to generate tissues and, theoretically, complex organs for transplantation. But this will require the perfection of techniques for directing their specialization into each of the component cell types and then the assembly of these cells in the correct proportion and spatial organization for an organ. That might be reasonably straightforward for a simple structure, such as a pancreatic islet that produces insulin, but it is more challenging for tissues as complex as that from lung, kidney, or liver [54; 55].

The experimental procedures required to produce stem cells through nuclear transplantation would consist of the transfer of a somatic cell nucleus from a patient into an enucleated egg, the in vitro culture of the embryo to the blastocyst stage, and the derivation of a pluripotent ES cell line from the inner cell mass of this blastocyst. Such stem cell lines would then be used to derive specialized cells (and, if possible, tissues and organs) in laboratory culture for therapeutic transplantation. Such a procedure, if successful, can avoid a major cause of transplant rejection. However, there are several possible drawbacks to this proposal. Experiments with animal models suggest that the presence of divergent mitochondrial proteins in cells may create “minor” transplantation antigens [56; 57] that can cause rejection [58- 63]; this would not be a problem if the egg were donated by the mother of the transplant recipient or the recipient herself. For some autoimmune diseases, transplantation of cells cloned from the patient's own cells may be inappropriate, in that these cells can be targets for the ongoing destructive process. And, as with the use of adult stem cells, in the case of a disorder that has a genetic origin, ES cells derived by nuclear transplantation from the patient's own cells would carry the same defect and would have to be grown and genetically modified before they could be used for therapeutic transplantation. Using another source of stem cells is more likely to be feasible (although immunosuppression would be required) than the challenging task of correcting the one or more genes that are involved in the disease in adult stem cells or in a nuclear transplantation-derived stem cell line initiated with a nucleus from the patient.

In addition to nuclear transplantation, there are two other methods by which researchers might be able to derive ES cells with reduced likeli hood for rejection. A bank of ES cell lines covering many possible genetic makeups is one possibility, although the National Academies report entitled Stem Cells and the Future of Regenerative Medicine rated this as “difficult to conceive” [11]. Alternatively, embryonic stem cells might be engineered to eliminate or introduce certain cell-surface proteins, thus making the cells invisible to the recipient's immune system. As with the proposed use of many types of adult stem cells in transplantation, neither of these approaches carries anything close to a promise of success at the moment.

The preparation of embryonic stem cells by nuclear transplantation differs from reproductive cloning in that nothing is implanted in a uterus. The issue of whether ES cells alone can give rise to a complete embryo can easily be misinterpreted. The titles of some reports suggest that mouse embryos can be derived from ES cells alone [64- 72]. In all cases, however, the ES cells need to be surrounded by cells derived from a host embryo, in particular trophoblast and primitive endoderm. In addition to forming part of the placenta, trophoblast cells of the blastocyst provide essential patterning cues or signals to the embryo that are required to determine the orientation of its future head and rump (anterior-posterior) axis. This positional information is not genetically determined but is acquired by the trophoblast cells from events initiated soon after fertilization or egg activation. Moreover, it is critical that the positional cues be imparted to the inner cells of the blastocyst during a specific time window of development [73- 76]. Isolated inner cell masses of mouse blastocysts do not implant by themselves, but will do so if combined with trophoblast vesicles from another embryo [77]. By contrast, isolated clumps of mouse ES cells introduced into trophoblast vesicles never give rise to anything remotely resembling a postimplantation embryo, as opposed to a disorganized mass of trophoblast. In other words, the only way to get mouse ES cells to participate in normal development is to provide them with host embryonic cells, even if these cells do not remain viable throughout gestation (Richard Gardner, personal communication). It has been reported that human [ 20] and primate [78- 79] ES cells can give rise to trophoblast cells in culture. However, these trophoblast cells would presumably lack the positional cues normally acquired during the development of a blastocyst from an egg. In the light of the experimental results with mouse ES cells described above, it is very unlikely that clumps of human ES cells placed in a uterus would implant and develop into a fetus. It has been reported that clumps of human ES cells in culture, like clumps of mouse ES cells, give rise to disorganized aggregates known as embryoid bodies [80].

Besides their uses for therapeutic transplantation, ES cells obtained by nuclear transplantation could be used in laboratories for several types of studies that are important for clinical medicine and for fundamental research in human developmental biology. Such studies could not be carried out with mouse or monkey ES cells and are not likely to be feasible with ES cells prepared from normally fertilized blastocysts. For example, ES cells derived from humans with genetic diseases could be prepared through nuclear transplantation and would permit analysis of the role of the mutated genes in both cell and tissue development and in adult cells difficult to study otherwise, such as nerve cells of the brain. This work has the disadvantage that it would require the use of donor eggs. But for the study of many cell types there may be no alternative to the use of ES cells; for these cell types the derivation of primary cell lines from human tissues is not yet possible.

If the differentiation of ES cells into specialized cell types can be understood and controlled, the use of nuclear transplantation to obtain genetically defined human ES cell lines would allow the generation of genetically diverse cell lines that are not readily obtainable from embryos that have been frozen or that are in excess of clinical need in IVF clinics. The latter do not reflect the diversity of the general population and are skewed toward genomes from couples in which the female is older than the period of maximal fertility or one partner is infertile. In addition, it might be important to produce stem cells by nuclear transplantation from individuals who have diseases associated with both simple

and complex (multiple-gene) heritable genetic predilections. For example, some people have mutations that predispose them to “Lou Gehrig's disease” (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS); however, only some of these individuals become ill, presumably because of the influence of additional genes. Many common genetic predilections to diseases have similarly complex etiologies; it is likely that more such diseases will become apparent as the information generated by the Human Genome Project is applied. It would be possible, by using ES cells prepared with nuclear transplantation from patients and healthy people, to compare the development of such cells and to study the fundamental processes that modulate predilections to diseases.

Neither the work with ES cells, nor the work leading to the formation of cells and tissues for transplantation, involves the placement of blastocysts in a uterus. Thus, there is no embryonic development beyond the 64 to 200 cell stage, and no fetal development.

FINDINGS

2-1. Reproductive cloning involves the creation of individuals that contain identical sets of nuclear genetic material (DNA). To have complete genetic identity, clones must have not only the same nuclear genes, but also the same mitochondrial genes.

2-2. Cloned mammalian animals can be made by replacing the chromosomes of an egg cell with a nucleus from the individual to be cloned, followed by stimulation of cell division and implantation of the resulting embryo.

2-3. Cloned individuals, whether born at the same or different times, will not be physically or behaviorally identical with each other at comparable ages.

2-4. Stem cells are cells that have an extensive ability to self-renew and differentiate, and they are therefore important as a potential source of cells for therapeutic transplantation. Embryonic stem cells derived through nuclear transplantation into eggs are a potential source of pluripotent (embryonic) stem cell lines that are immunologically similar to a patient's cells. Research with such cells has the goal of producing cells and tissues for therapeutic transplantation with minimal chance of rejection.

2-5. Embryonic stem cells and cell lines derived through nuclear transplantation could be valuable for uses other than organ transplantation. Such cell lines could be used to study the heritable genetic components associated with predilections to a variety of complex genetic diseases and test therapies for such diseases when they affect cells that are hard to study in isolation in adults.

2-6. The process of obtaining embryonic stem cells through nuclear transplantation does not involve the placement of an embryo in a uterus, and it cannot produce a new individual.

REFERENCES

1. COLMAN A. Somatic cell nuclear transfer in mammals: Progress and applications . Cloning 1999, 1(4): 185-200.

2. WOLF E, ZAKHARTCHENKO V, BREM G. Nuclear transfer in mammals: recent developments and future perspectives . J Biotechnol 1998 Oct 27(65) 2-3:

99-110.

3. CHAN AW, DOMINKO T, LUETJENS CM, NEUBER E, MARTINOVICH C, HEWITSON L, SIMERLY CR, SCHATTEN GP. Clonal propagation of primate offspring by embryo splitting . Science 2000 Jan 14, 287(5451): 317-319.

4. HALL JG. Twinning: mechanisms and genetic implications . Curr Opin Genet Dev 1996 Jun, 6(3): 343-7.

5. HALL JG. Genomic imprinting: nature and clinical relevance . Annu Rev Med 1997, 48: 35-44.

6. SIMON DK, JOHNS DR. Mitochondrial disorders: clinical and genetic features . Annu Rev Med 1999, 50: 111-27.

7. FINNILA S, AUTERE J, LEHTOVIRTA M, HARTIKAINEN P, MANNERMAA A, SOININEN H, MAJAMAA K. Increased risk of sensorineural hearing loss and migraine in patients with a rare mitochondrial DNA variant 4336A>G in tRNAGln . J Med Genet 2001 Jun, 38(6): 400-5.

8. MCCREATH KJ, HOWCROFT J, CAMPBELL KH, COLMAN A, SCHNIEKE AE, KIND AJ. Production of gene-targeted sheep by nuclear transfer from cultured somatic cells . Nature 2000 Jun 29, 405(6790): 1066-9.

9. SCHNIEKE AE, KIND AJ, RITCHIE WA, MYCOCK K, SCOTT AR, RITCHIE M, WILMUT I, COLMAN A, CAMPBELL KH. Human factor IX transgenic sheep produced by transfer of nuclei from transfected fetal fibroblasts . Science 1997 Dec 19, 278(5346): 2130-3.

10. FIDDLER M, PERGAMENT D, PERGAMENT E. The role of the preimplantation geneticist in human cloning . Prenat Diagn 1999 Dec, 19(13): 1200-4.

11. COMMITTEE ON STEM CELLS AND THE FUTURE OF REGENERATIVE MEDICINE, BOARD ON LIFE SCIENCES AND BOARD ON NEUROSCIENCE AND BEHAVIORAL HEALTH. Stem Cells and the Future of Regenerative Medicine. Report of the National Academy of Sciences and the Institute of Medicine . 2001 Sep.

12. BAUM CM, WEISSMAN IL, TSUKAMOTO AS, BUCKLE AM, PEAULT B. Isolation of a candidate human hematopoietic stem-cell population . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1992 Apr 01, 89(7): 2804-8.

13. AZIZI SA, STOKES D, AUGELLI BJ, DIGIROLAMO C, PROCKOP DJ. Engraftment and migration of human bone marrow stromal cells implanted in the brains of albino rats—similarities to astrocyte grafts . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998 Mar 31, 95(7): 3908-13.

14. UCHIDA N, BUCK DW, HE D, REITSMA MJ, MASEK M, PHAN TV, TSUKAMOTO AS, GAGE FH, WEISSMAN IL. Direct isolation of human central nervous system stem cells . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000 Dec 19, 97(26): 14720-5.

15. PALMER TD, SCHWARTZ PH, TAUPIN P, KASPAR B, STEIN SA, GAGE FH. Cell culture. Progenitor cells from human brain after death . Nature 2001 May 03, 411(6833): 42-3.

16. ZUK PA, ZHU M, MIZUNO H, HUANG J, FUTRELL JW, KATZ AJ, BENHAIM P, LORENZ HP, HEDRICK MH. Multilineage cells from human adipose tissue: implications for cell-based therapies . Tissue Eng 2001 Apr, 7(2): 211-28.

17. KRAUSE DS, THEISE ND, COLLECTOR MI, HENEGARIU O, HWANG S, GARDNER R, NEUTZEL S, SHARKIS SJ. Multi-organ, multi-lineage engraftment by a single bone marrow-derived stem cell . Cell 2001 May 04, 105(3): 369-77.

18. TOMA JG, AKHAVAN M, FERNANDES KJL, BARNABÉ-HEIDER F, SADIKOT A, KAPLAN DR, MILLER FD. Isolation of multipotent adult stem cells from the dermis of mammalian skin . Nature Cell Biology 2001 Sep, 3 778-784.

19. RIETZE RL, VALCANIS H, BROOKER GF, THOMAS T, VOSS AK, BARTLETT PF. Purification of a pluripotent neural stem cell from the adult mouse brain. Nature 2001 Aug 16, 412(6848): 736-9.

20. THOMSON JA, ITSKOVITZ-ELDOR J, SHAPIRO SS, WAKNITZ MA, SWIERGIEL JJ, MARSHALL VS, JONES JM. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts . Science 1998 Nov 06, 282(5391): 1145-7.

21. EVANS MJ, KAUFMAN MH. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos . Nature 1981 Jul 09, 292(5819): 154-6.

22. MARTIN GR. Isolation of a pluripotent cell line from early mouse embryos cultured in medium conditioned by teratocarcinoma stem cells . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1981 Dec, 78(12): 7634-8.

23. REUBINOFF BE, PERA MF, FONG CY, TROUNSON A, BONGSO A. Embryonic stem cell lines from human blastocysts: somatic differentiation in vitro . Nat Biotechnol 2000 Apr, 18(4): 399-404.

24. SHINOHARA T, BRINSTER RL. Enrichment and transplantation of spermatogonial stem cells . Int J Androl 2000, 23 Suppl 2: 89-91.

25. WEISSMAN IL. Translating stem and progenitor cell biology to the clinic: Barriers and opportunities . Science 2000 Feb 25, 287(5457): 1442-6.

26. LAGASSE E, SHIZURU JA, UCHIDA N, TSUKAMOTO A, WEISSMAN IL. Toward regenerative medicine . Immunity 2001 Apr, 14(4): 425-36.

27. GUSSONI E, SONEOKA Y, STRICKLAND CD, BUZNEY EA, KHAN MK, FLINT AF, KUNKEL LM, MULLIGAN RC. Dystrophin expression in the mdx mouse restored by stem cell transplantation . Nature 1999 Sep 23, 401(6751): 390-4.

28. LEE SH, LUMELSKY N, STUDER L, AUERBACH JM, MCKAY RD. Efficient generation of midbrain and hindbrain neurons from mouse embryonic stem cells . Nat Biotechnol 2000 Jun, 18(6): 675-9.

29. WAKAYAMA T, TABAR V, RODRIGUEZ I, PERRY AC, STUDER L, MOMBAERTS P. Differentiation of embryonic stem cell lines generated from adult somatic cells by nuclear transfer . Science 2001 Apr 27, 292(5517): 740-3.

30. LUMELSKY N, BLONDEL O, LAENG P, VELASCO I, RAVIN R, MCKAY R. Differentiation of embryonic stem cells to insulin-secreting structures similar to pancreatic islets . Science 2001 May 18, 292(5520): 1389-94.

31. SHAMBLOTT MJ, AXELMAN J, LITTLEFIELD JW, BLUMENTHAL PD, HUGGINS GR, CUI Y, CHENG L, GEARHART JD. Human embryonic germ cell derivatives express a broad range of developmentally distinct markers and proliferate extensively in vitro . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001 Jan 02, 98(1): 113-8.

32. NEGRIN RS, ATKINSON K, LEEMHUIS T, HANANIA E, JUTTNER C, TIERNEY K, HU WW, JOHNSTON LJ, SHIZURN JA, STOCKERL-GOLDSTEIN KE, BLUME KG, WEISSMAN IL, BOWER S, BAYNES R, DANSEY R, KARANES C, PETERS W, KLEIN J. Transplantation of highly purified CD34+Thy-1+ hematopoietic stem cells in patients with metastatic breast cancer . Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2000, 6(3): 262-71.

33. FERRARI G, CUSELLA-DE ANGELIS G, COLETTA M, PAOLUCCI E, STORNAIUOLO A, COSSU G, MAVILIO F. Muscle regeneration by bone marrow-derived myogenic progenitors . Science 1998 Mar 06, 279(5356): 1528-30.

34. PETERSEN BE, BOWEN WC, PATRENE KD, MARS WM, SULLIVAN AK, MURASE N, BOGGS SS, GREENBERGER JS, GOFF JP. Bone marrow as a potential source of hepatic oval cells . Science 1999 May 14, 284(5417): 1168-70.

35. ALISON MR, POULSOM R, JEFFERY R, DHILLON AP, QUAGLIA A, JACOB J, NOVELLI M, PRENTICE G, WILLIAMSON J, WRIGHT NA. Hepatocytes from non-hepatic adult stem cells . Nature 2000 Jul 20, 406(6793): 257.

36. BONNER-WEIR S, TANEJA M, WEIR GC, TATARKIEWICZ K, SONG KH, SHARMA A, O'NEIL JJ. In vitro cultivation of human islets from expanded ductal tissue . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000 Jul 05, 97(14): 7999-8004.

37. CLARKE DL, JOHANSSON CB, WILBERTZ J, VERESS B, NILSSON E, KARLSTROM H, LENDAHL U, FRISEN J. Generalized potential of adult neural stem cells . Science 2000 Jun 02, 288(5471): 1660-3.

38. LAGASSE E, CONNORS H, AL-DHALIMY M, REITSMA M, DOHSE M, OSBORNE L, WANG X, FINEGOLD M, WEISSMAN IL, GROMPE M. Purified hematopoietic stem cells can differentiate into hepatocytes in vivo . Nat Med 2000 Nov, 6(11): 1229-34.

39. MEZEY E, CHANDROSS KJ, HARTA G, MAKI RA, MCKERCHER SR. Turning blood into brain: cells bearing neuronal antigens generated in vivo from bone marrow . Science 2000 Dec 01, 290(5497): 1779-82.

40. FALLON J, REID S, KINYAMU R, OPOLE I, OPOLE R, BARATTA J, KORC M, ENDO TL, DUONG A, NGUYEN G, KARKEHABADHI M, TWARDZIK D, PATEL S, LOUGHLIN S. In vivo induction of massive proliferation, directed migration, and differentiation of neural cells in the adult mammalian brain . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000 Dec 19, 97(26): 14686-91.

41. BRAZELTON TR, ROSSI FM, KESHET GI, BLAU HM. From marrow to brain: expression of neuronal phenotypes in adult mice . Science 2000 Dec 01, 290(5497): 1775-9.

42. KOCHER AA, SCHUSTER MD, SZABOLCS MJ, TAKUMA S, BURKHOFF D, WANG J, HOMMA S, EDWARDS NM, ITESCU S. Neovascularization of ischemic myocardium by human bone-marrow-derived angioblasts prevents cardiomyocyte apoptosis, reduces remodeling and improves cardiac function . Nat Med 2001 Apr, 7(4): 430-6.

43. ANDERSON DJ, GAGE FH, WEISSMAN IL. Can stem cells cross lineage boundaries? Nat Med 2001 Apr, 7(4): 393-5.

44. LANZA RP, CAPLAN AL, SILVER LM, CIBELLI JB, WEST MD, GREEN RM. The ethical validity of using nuclear transfer in human transplantation . JAMA 2000 Dec 27, 284(24): 3175-9.

45. WEISSMAN IL, BALTIMORE D. Disappearing stem cells, disappearing science . Science 2001 Apr 27, 292(5517): 601.

46. WINSTON R. Embryonic stem cell research: The case for… Nat Med 2001 Apr, 7(4): 396-397.

47. VOGEL G. Stem cell policy. Can adult stem cells suffice? Science 2001 Jun 08, 292(5523): 1820-2.

48. GURDON JB, COLMAN A. The future of cloning . Nature 1999 Dec 16, 402(6763): 743-6.

49. PERA MF, REUBINOFF B, TROUNSON A. Human embryonic stem cells . J Cell Sci 2000 Jan, 113(Pt 1): 5-10.

50. ODORICO JS, KAUFMAN DS, THOMSON JA. Multilineage differentiation from human embryonic stem cell lines . Stem Cells 2001, 19(3): 193-204.

51. STUDER L, TABAR V, MCKAY RD. Transplantation of expanded mesencephalic precursors leads to recovery in parkinsonian rats . Nat Neurosci 1998 Aug, 1(4): 290-5.

52. MCDONALD JW, LIU XZ, QU Y, LIU S, MICKEY SK, TURETSKY D, GOTTLIEB DI, CHOI DW. Transplanted embryonic stem cells survive, differentiate and promote recovery in injured rat spinal cord . Nat Med 1999 Dec, 5(12): 1410-2.

53. LANZA RP, CIBELLI JB, WEST MD. Prospects for the use of nuclear transfer in human transplantation . Nat Biotechnol 1999 Dec, 17(12): 1171-4.

54. MUNSIE MJ, MICHALSKA AE, O'BRIEN CM, TROUNSON AO, PERA MF, MOUNTFORD PS. Isolation of pluripotent embryonic stem cells from reprogrammed adult mouse somatic cell nuclei . Curr Biol 2000 Aug 24, 10(16): 989-92.

55. SIMPSON E. Minor transplantation antigens: animal models for human host-versus-graft, graft-versus-host, and graft-versus-leukemia reactions . Transplantation 1998 Mar 15, 65(5): 611-6.

56. SIMPSON E, ROOPENIAN D. Minor histocompatibility antigens . Curr Opin Immunol 1997 Oct, 9(5): 655-61.

57. CHAN T, FISCHER LINDAHL K. Skin graft rejection caused by the maternally transmitted antigen Mta . Transplantation 1985 May, 39(5): 477-80.

58. FISCHER LINDAHL K, HERMEL E, LOVELAND BE, WANG CR. Maternally transmitted antigen of mice: a model transplantation antigen . Annu Rev Immunol 1991, 9: 351-72.

59. DAVIES JD, SILVERS WK, WILSON DB. A transplantation antigen, possibly of mitochondrial origin, that elicits rejection of parental strain skin grafts by F1 rats . Transplantation 1992 Oct, 54(4): 730-1.

60. DABHI VM, LINDAHL KF. MtDNA-encoded histocompatibility antigens . Methods Enzymol 1995, 260: 466-85.

61. DABHI VM, LINDAHL KF. CTL respond to a mitochondrial antigen presented by H2-Db . Immunogenetics 1996, 45(1): 65-8.

62. BHUYAN PK, YOUNG LL, LINDAHL KF, BUTCHER GW. Identification of the rat maternally transmitted minor histocompatibility antigen . J Immunol 1997 Apr 15, 158(8): 3753-60.

63. AMANO T, KATO Y, TSUNODA Y. Comparison of heat-treated and tetraploid blastocysts for the production of completely ES-cell-derived mice . Zygote 2001 May, 9(2): 153-7.

64. AMANO T, NAKAMURA K, TANI T, KATO Y, TSUNODA Y. Production of mice derived entirely from embryonic stem cells after injecting the cells into heat treated blastocysts . Theriogenology 2000 Apr 15, 53(7): 1449-58.

65. EGGAN K, AKUTSU H, LORING J, JACKSON-GRUSBY L, KLEMM M, RIDEOUT WM 3rd, YANAGIMACHI R, JAENISCH R. Hybrid vigor, fetal overgrowth, and viability of mice derived by nuclear cloning and tetraploid embryo complementation . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001 May 22, 98(11): 6209-14.

66. IWASAKI S, CAMPBELL KH, GALLI C, AKIYAMA K. Production of live calves derived from embryonic stem-like cells aggregated with tetraploid embryos. Biol Reprod 2000 Feb, 62(2): 470-5.

67. NAGY A, GOCZA E, DIAZ EM, PRIDEAUX VR, IVANYI E, MARKKULA M, ROSSANT J. Embryonic stem cells alone are able to support fetal development in the mouse . Development 1990 Nov, 110(3): 815-21.

68. NAGY A, ROSSANT J, NAGY R, ABRAMOW-NEWERLY W, RODER JC. Derivation of completely cell culture-derived mice from early-passage embryonic stem cells . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1993 Sep 15, 90(18): 8424-8.

69. TANAKA M, HADJANTONAKIS AK, NAGY A. Aggregation chimeras. Combining ES cells, diploid and tetraploid embryos . Methods Mol Biol 2001, 158: 135-54.

70. UEDA O, JISHAGE K, KAMADA N, UCHIDA S, SUZUKI H. Production of mice entirely derived from embryonic stem (ES) cell with many passages by coculture of ES cells with cytochalasin B induced tetraploid embryos . Exp Anim 1995 Jul, 44(3): 205-10.

71. WANG ZQ, KIEFER F, URBANEK P, WAGNER EF. Generation of completely embryonic stem cell-derived mutant mice using tetraploid blastocyst injection . Mech Dev 1997 Mar, 62(2): 137-45.

72. BEDDINGTON RS, ROBERTSON EJ. Axis development and early asymmetry in mammals . Cell 1999 Jan 22, 96(2): 195-209.

73. GARDNER RL. Axial relationships between egg and embryo in the mouse . Curr Top Dev Biol 1998, 39: 35-71.

74. GARDNER RL. The initial phase of embryonic patterning in mammals . Int Rev Cytol 2001, 203: 233-90.

75. GARDNER RL. Specification of embryonic axes begins before cleavage in normal mouse development . Development 2001 Mar, 128(6): 839-47.

76. GARDNER, R. L. An investigation of inner cell mass and trophoblast tissues following their isolation from the mouse blastocyst . J. Embryol exp. Morphology 1972(28): 279-312.

77. THOMSON JA, MARSHALL VS. Primate embryonic stem cells . Curr Top Dev Biol 1998, 38: 133-65.

78. THOMSON JA, KALISHMAN J, GOLOS TG, DURNING M, HARRIS CP, BECKER RA, HEARN JP. Isolation of a primate embryonic stem cell line . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995 Aug 15, 92(17): 7844-8.

79. ITSKOVITZ-ELDOR, J., SCHULDINER, M., KARSENTI, D., EDEN, A., YANUKA, O., AMIT, M., SOREQ, H., AND BENVENISTY, N. Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into embryoid bodies compromising the three embryonic germ layers . Mol Med. 2000(6): 88-95.

80. RECHITSKY S, STROM C, VERLINSKY O, AMET T, IVAKHNENKO V, KUKHARENKO V, KULIEV A, VERLINSKY Y. Accuracy of preimplantation diagnosis of single-gene disorders by polar body analysis of oocytes . J Assist Reprod Genet 1999 Apr, 16(4): 192-8.

REFERENCE

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK223960/

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/eve-first-human-clone/

https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn3217-first-cloned-baby-born-on-26-december/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK223960/

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/eve-first-human-clone/

https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn3217-first-cloned-baby-born-on-26-december/

CLEOPATRA

THE MUMMY - UNDER DEVELOPMENT

'Cleopatra

- The Mummy' followed 'Kulo-Luna.'

Kulo-Luna, the first script of the John Storm franchise (for which a

draft

is published). The John Storm

franchise is a series of

ocean awareness adventures, featuring the incredible solar

powered trimaran: Elizabeth

Swann. 'Cleopatra The Mummy,' could be made and released

in any order with or without,

Kulo-Luna, or Treasure Island

as prequel or sequel. The

order of production could be to suit identified gaps in

entertainment, in any particular year, as and when such gap

in the market become profitable. Equally, a trilogy or

series

could be adapted for network television, as with Blood

and Treasure from CBS.

|