A

superb depiction of Cleopatra taking her own life, unlikely to have been by

the handling of a snake, but could well have been by an asp in a basket of

fruit. Most probably with a concoction of drugs to ease the pain.

More than 2,000 years after her death in 30

BCE, the Egyptian queen

Cleopatra still looms large in the popular imagination.

While

the

search continues for the resting place of Cleopatra,

and her long lost

missing tomb, apart from what she may have looked like, other question on everyone's mind is

how the Ancient

Egyptian Pharaoh Queen looked after her teeth.

The ancient Egyptians believed that cleanliness was important for both physical and spiritual well-being. Their hygiene system was complex, encompassing bathing, shaving, and dental care.

The ancients invented toothpaste. The paste was made of mint, rock salt, pepper, and dried iris flower.

The toothbrushes they used were made of a frayed stick, later developed into a notched stick with entwined plant bristles.

Apparently very effective, but not a patch on modern synthetic plastic

brushes, that come in a range of patterns and hardness's.

To freshen their breath, the ancients used mints sold by merchants, made from a mixture of frankincense, cinnamon, melon, pine seeds, and cashews, commonly mixed with honey. These

candies likely a forerunner of after-dinner mints.

Undiluted natron – a sodium bicarbonate substance – was used as toothpaste and mouthwash. Ancient Egyptians chewed on parsley

and others herbs to freshen breath throughout the day.

Modern archaeological findings show little evidence of tooth decay among ancient Egyptians.

The question is, why was this. And, could it be that with Cleopatra VII

her oral hygiene improved as she aged and needed to better her appearance.

The historical evidence is somewhat sketchy and contradictory. What is

supposed in the fictional 'Cleopatra

Reborn' adventure, is that at least some of the queen's teeth were

sufficiently well preserved to enable Rudolph

Kessler and Klaus

von Kolreuter to extract sufficient quality DNA

for their digital reincarnation experiments.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL

STUDIES

In

ancient Egypt the exceptionally dry climate together with the unique burial customs has resulted in the survival of large numbers of well-preserved skeletal and

mummified remains. Examinations of these remains together with an analysis of the surviving documentary, archaeological and ethnographic evidence has enabled a detailed picture of the dental health of these ancient people to be revealed, perhaps more so than for any other civilisation in antiquity.

The dental pathological conditions that afflicted the ancient Egyptians is

worthy of consideration. The commonest finding is that of tooth wear, which was often so excessive that it resulted in pulpal exposure. Multiple abscesses were frequently seen, but

was not a significant problem. Overall the findings of archaeological

studies indicate that the various pathological conditions and non-pathological abnormalities of teeth evident in dentitions in the

twenty-first century were also manifest in ancient Egypt, although the incidences of these conditions varies considerably between the

civilisations.

Beautiful as history has portrayed her, the front teeth of Cleopatra VII (69 BC – 30

BC) Queen of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt, were said to be fused with tartar deposits. Despite this she became one of the world’s most famous seductresses.

In the grand scheme of things, teeth can tell tales of ancient diets and lifestyles. From fibrous foods acting as natural toothbrushes to

Cleopatra’s unfortunate tartar situation, our ancestors had their dental stories to tell.

A study on ancient Britons revealed that 4,000 years ago, their teeth were “highly mobile.” A fancy way of saying people had loose teeth back then. Historians play detective with ancient texts, cooking utensils and skeletal remains to piece together the puzzle of our ancestors’ diets.

A study of medieval English children’s teeth used 3D imaging to peek into the enamel of kids who lived between the 11th and 16th centuries. These youngsters were weaned by one, fed a mix of raw milk concoction and bread broth, and graduated to adult foods by age seven. Compare that to today’s children with their processed snacks, as a stark difference.

Despite their seemingly bland diet, medieval children had the upper hand in dental health. No processed foods and hidden sugars meant fewer cavities. Sugar and not brushing regularly is the enemy of a heathy mouth and good teeth.

Today’s babies are fed fruit and sugar-infused vegetable purees, upgrading to an almost adult diet as soon as they can chew.

THE

TOOTHPICK

The oldest oral hygiene tool is the toothpick. They have been around from the dawn of recorded time, either to simply remove food debris from the interdental space or as jewelry, as it became fashionable during the Medieval Time, to demonstrate one’s social status. The earliest forms of toothpick, during the

Neanderthal and Paleolithic periods were probably made of bone or wood. Alone or in combination with an ear scoop, dental scraper, or even hunting whistle, made of a quill, wood, ivory, bamboo, bronze, iron, copper, silver or gold, toothpicks have a rich history. In many instances these tools were attached as a “grooming set” for personal use and displayed on one’s chest or belt.

Early evidence for such sets comes from grave sites where burial of one’s utilities to accompany the dead into the afterlife was common practice. In addition, wooden fibers found in grooves of lower teeth, facing the interdental space of early cavemen indicates the use of toothpicks 1.2 million years ago. The earliest grooming set dates from 3000 years BCE Mesopotamia.

During the excavations conducted in 1847 at Nineveh by Henry Layard, the British archeologist, 660 tablets with cuneiform writing were uncovered. They were from the time of Enlil-Bani, King of Isinth (1798-1775 BCE) and contained medical recipes and description on the use of toothpicks. The tablets also contained curative incantations for diseases of the mouth, teeth and to treat halitosis and excessive salivation.

Some early toothpicks were not man-made. Rather, they were natural, obtained from the dried flowers of the Amni visnaga, a plant originally from the

Nile Delta. Also known as “bushnika” in

Morocco, and commonly referred as the “toothpick flower” plant, their medicinal use is mentioned in the Ebers Papyrus.

In ancient Greece and Rome, the mastic tree (Pistuciu zenticus) that gave rise to the early toothbrush (miswak in the Middle East and Africa) was used to fashion wooden toothpicks. The Greek word used for toothpick was karphos, which translates as a “blade of straw.” In addition to wood, feather or

silver toothpicks were also employed. For instance, Diodorus Siculus described that Agathokles (317-289 BCE), the ruler of Syracuse used a toothpick cut from a quill. Pliny advised, “picking the teeth with the quill of a vulture turns the breath sour while a porcupine’s quill makes the teeth firm.” He also recommended using a “needle-sharp hare’s bone” to prevent halitosis. Feathers were used both as toothpicks and toothbrushes; the cut end of the quill to pick, and the feather end to brush. Others, like Trimalchio, a character in Gaius Petronius Arbiter’s first century work the Satyricon, “picked his teeth with a silver toothpick” (…dentes spina argentea perfodiebat).

THE TOOTHBRUSH

The toothbrush with all its bristles, innovative designs, and technolgical enhancements, has not alway been around. The actual toothbrush as we know it today was not invented until 1938.

It must be duly noted however, that there were MANY forms of toothbrushing tools invented way before the late 1930s. There have been findings of toothsticks in ancient Egyptian tombs. The Chinese also made their own rendition of toothbrushes such as, chewing sticks, that could be traced back to 1600 BC. Way back when in 3500 - 3000 BC the babylonians made their own brush by fraying the end of a twig. So it is safe to say that through the ages, the concept of a toothbrush has been around in some type of form, and it is very much still present today, worldwide.

The concept of this discovery was passed down through time and also through different land masses and it was customized by various of different cultures all leading up to the toothrush that we see today at any local store. Even in present day today, there seems to be an interest in going back to the original wooden type of toothbrush due to the plastic design that has been more common.

MOUTHWASH

Cleaning one’s mouth were advocated from ancient times either by mechanical or chemical means. Rubbing with a cloth, a stick, a brush, combined with an abrasive powder were recommended. The earliest evidence of the use of a mouthwash was in Ancient China and India. It contained an extract of the Barringtonia tree mixed with “mustard, Bengal pepper, ginger, alkaline ash and salt”.

The Roman poet Gaius Catullus recommended daily gargling with one’s own urine, as both, Diodorus Siculus (90-30 BCE) and Strabo (64 BCE-21CE) claimed that the Celtiberians living on the Iberian peninsula: “use urine to bathe the body and wash their teeth”.

A typical description of how one should keep one’s mouth clean is found in Zene Artzney, the first book dedicated exclusively to dental remedies published in 1530. In William Vaughn’s 1602 treaties on the “Naturall and Artificial Directions for Health” these suggestions are made: “take a linen cloth, and rub your teeth well within and without, ….Take halfe a glasse-full of vineger, and as much of the water of the mastick tree of rosemarie, myrrhe, mastick, bole Armoniake, Dragons herbe, roche allome, of each of them an ounce (….) and wash your teeth therewithall as well before meate as after”.

The initial impetus for cleaning one’s mouth and teeth was primarily prevention of bad breath rather than understanding a cause-effect relationship between bacterial byproducts and dental decay. In 1683 Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, the discoverer of the microscope, in a letter to Francis Aston, secretary of the the Royal Society describes bacteria for the first time: “there are more animals in the unclean matter on the teeth in a man’s mouth than there are men in the whole kingdom – especially in those who don’t ever clean their teeth, whereby such stench comes from the mouth of many of them, that can scarce bear to talk to them”.

SUGAR

Cavities are the most common cause of toothache today and are caused by consuming starchy or sugary food and drink including grains. They are often considered a relatively modern problem linked to the fact that the invention of farming introduced large amounts of carbohydrates, and more recently refined sugar, to our diets.

But recent research suggests this is not the case. In fact, cavities have now been found in tooth fossils from nearly every prehistoric hominin species studied. They were probably caused by eating certain fruits and vegetation as well as honey. These lesions were often severe, as in the case of cavities found on the teeth of the newly discovered species, Homo naledi. In fact, these cavities were so deep they probably took years to form and would almost certainly have caused serious toothache.

Dental erosion is one of the most common tooth problems in the world today. Fizzy drinks, fruit juice, wine, and other acidic food and drink are usually to blame, although perhaps surprisingly the way we clean our teeth also plays a role. This all makes it sound like a rather modern issue. But research suggests actually humans have been suffering dental erosion for millions of years.

If you brush your teeth too vigorously you can weaken dental tissue, which over time allows acidic foods and drinks to create deep holes known as non-carious cervical lesions (NCCLs).

Reseaarchers found such lesions on the fossilised teeth from a human ancestor species

Australopithecus

africanus. Given the lesions' size and position, this individual would likely have had toothache or sensitivity. So why did this prehistoric hominin have tooth problems that look indistinguishable from that caused by drinking large volumes of fizzy drinks today?

The answer may come back to another unlikely parallel. Erosive wear today is often also associated with aggressive tooth brushing. Australopithecus africanus probably experienced similar dental abrasion from eating tough and fibrous foods. For lesions to form, they would still have needed a diet high in acidic foods. Instead of fizzy drinks, this probably came in the form of citrus fruits and acidic vegetables. For example, tubers (potatoes and the like) are tough to eat and some can be surprisingly acidic, so they could have been a cause of the lesions.

Cleopatra VII

Philopator was (for sure) the daughter of Ptolemy XII Auletes (80-52BC), Pharaoh of Egypt and

(quite likely) Cleopatra V Tryphaena. There is a marked difference in facial

features between the busts and temple relief's. The one thing the Egyptian

carvings have in common, are the bare breasts. The signature tune of Egypt's

last Pharaoh Queen. Who is said to have asked Isis to be reborn, and made

all the funerary arrangements to thwart Ocavian, should he later realise her

plan to be reincarnated. Cleopatra rightly guessed that the technology to

make that a reality, would one day surface.

In Hollywood movies, Cleopatra has been played by an array of stunning

actresses, all with perfectly cosmetic teeth, probably as part of their

acting contracts.

Elizabeth Taylor, who was put under the “gaze” as the

“Queen of the

Nile” in the best-known film version of the ruler’s story to date, Cleopatra

(1963), is a mainstay on short lists of moviedom’s most attractive leading ladies. One of cinema’s first sex symbols, Theda Bara, invested her Cleopatra with dark sensuality in the lost silent classic

Cleopatra (1917). Before the Production Code reined in sexual suggestiveness, a scantily clad Claudette Colbert caused a sensation in

Cecil B. DeMille’s epic Cleopatra (1934), and Vivian Leigh was the beguiling queen in

Caesar and Cleopatra (1945).

In 2023, Gal

Gadot was said to be limbering up to play the part. As is Zendaya,

with Denis

Villeneuve advertised to direct a revisited

biopic in 2025, thought to be part funded by Sony

pictures.

It

is interesting to look at the gap in years between remakes of Cleopatra

biopics without CGI:

1917

-

1934

-

1945

-

1963

-

1972

-

And

then a massive interlude, movie moguls aware that the 1963 version almost

bankrupt 20th Century Fox.

So,

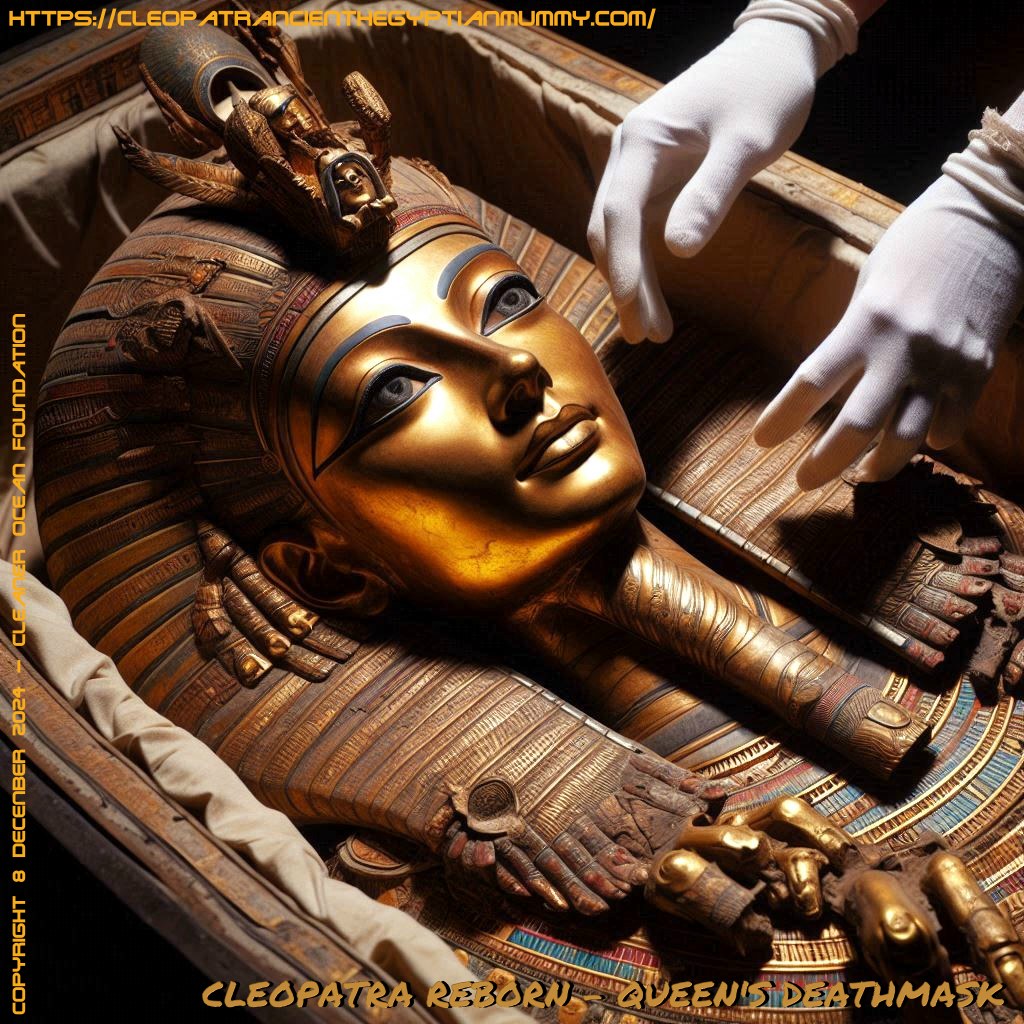

how did this image of Cleopatra come to be?

The obsession with Cleopatra as a stunner started much earlier than movies: it started in literature and drama. In his play

Antony and

Cleopatra, William Shakespeare indelibly etched the queen’s portrait with these words:

"Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale

Her infinite variety. Other women cloy

The appetites they feed, but she makes hungry

Where most she satisfies."

REFERENCE

Bellis, M. (n.d.). Who Invented the Toothbrush?

https://www.thoughtco.com/history-of-dentistry-and-dental-care-991569#brushpaste

Connelly, D. T. (2010 August 20). The History of the Toothbrush: From 5000 BC to Present.

https://www.huffingtonpost.com/thomas-p-connelly-dds/mouth-health-how-long-hav_b_683535.html

Green, J. (2014 October 01). Interesting Facts from the History of Orthodontics.

http://www.colgate.com/en/us/oc/oral-health/cosmetic-dentistry/early-orthodontics/article/interesting-facts-from-the-history-of-orthodontics-1014

Jarvis, W. T. (n.d.). Fluoridation.

https://www.ncahf.org/articles/e-i/fluoride.html

Luntz, S. (2017 October 14). New Find Suggest That Neanderthals Had Dental Care.

http://www.iflscience.com/health-and-medicine/neanderthal-toothpick-marks-show-they-had-primitive-dental-care/

Mark, Emily. (2016, January 28th). Shang Dynasty.

https://www.ancient.eu/Shang_Dynasty/Daniels

Mark, Joshua (2011) Cuneiform. Ancient History Encyclopedia.

https://www.ancient.eu/cuneiform/

Shata D. Miswak: First Toothbrush in History.

http://www.arabnews.com/news/459712#photo/0

Toothpaste Timeline.

https://www.nhsmiles.com/toothpaste-timeline/

The Evolution of Dental Care.

http://www.ossiandental.com/blog/the-evolution-of-dental-care/

The Great Depression. Retrieved October 31st from

http://www.history.com/topics/great-depression

|