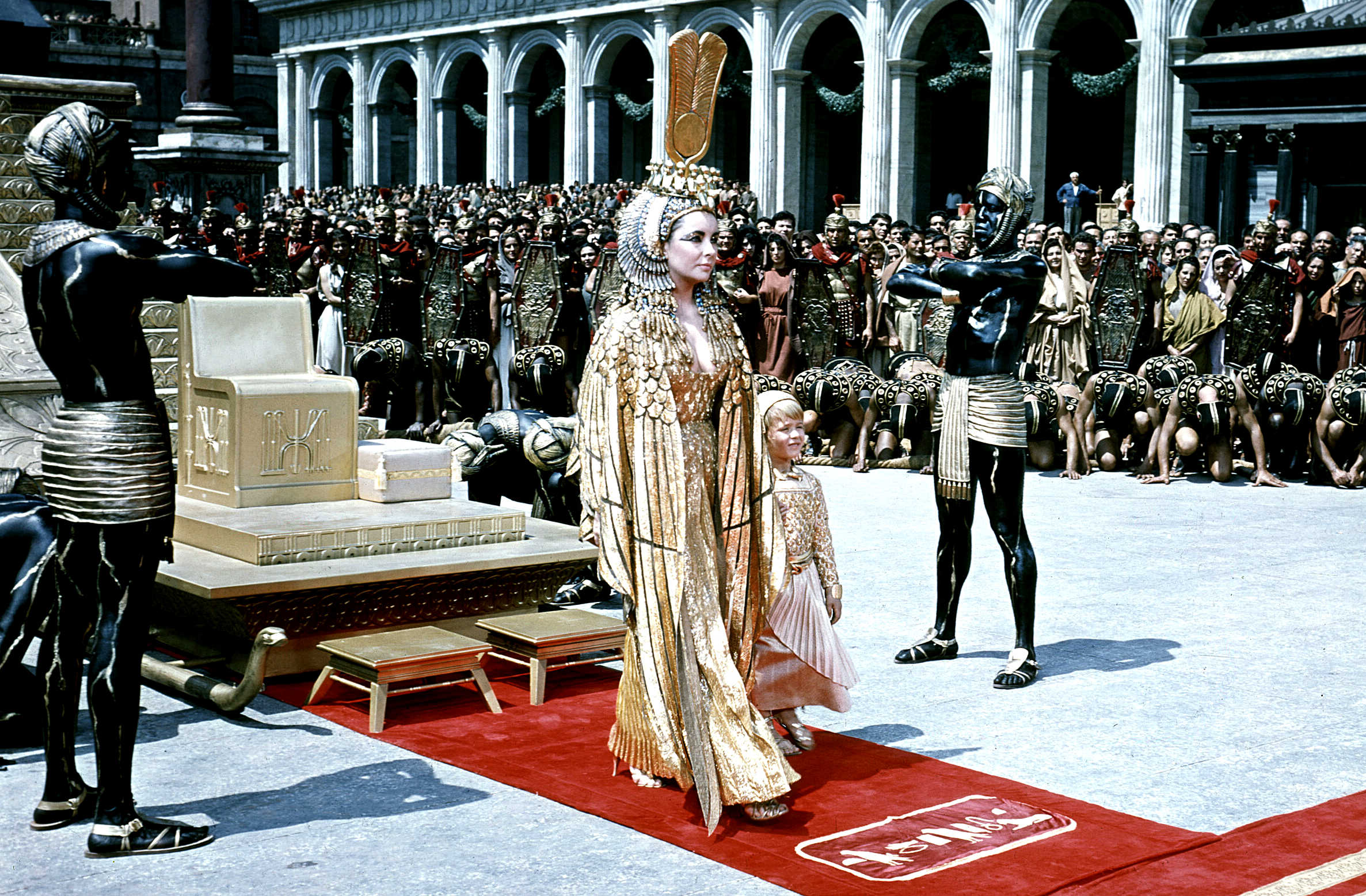

Sizzling:

Elizabeth Taylor, hit the mark, much as the real Cleopatra,

a real stunner.

The

first Cleopatra movie was made in

1917. It was silent and

most unfortunately, no

known prints of the William Fox film survive. The second

movie by Cecil B DeMille, starred Claudette

Colbert, from 1934, a box office success. The third

movie, an adaptation of George

Bernard Shaw's Caesar and Cleopatra, was made in 1945,

starring Vivien Leigh, that, despite the enigmatic Ms Leigh,

sent us into snooze land, almost from the moment the DVD was

played - and we are fans of Vivien. The fourth picture starred Charlton Heston,

made in 1972, and we cannot imagine why this movie went

ahead. Except to keep the fabulous Heston doing what we did

best on the big screen.

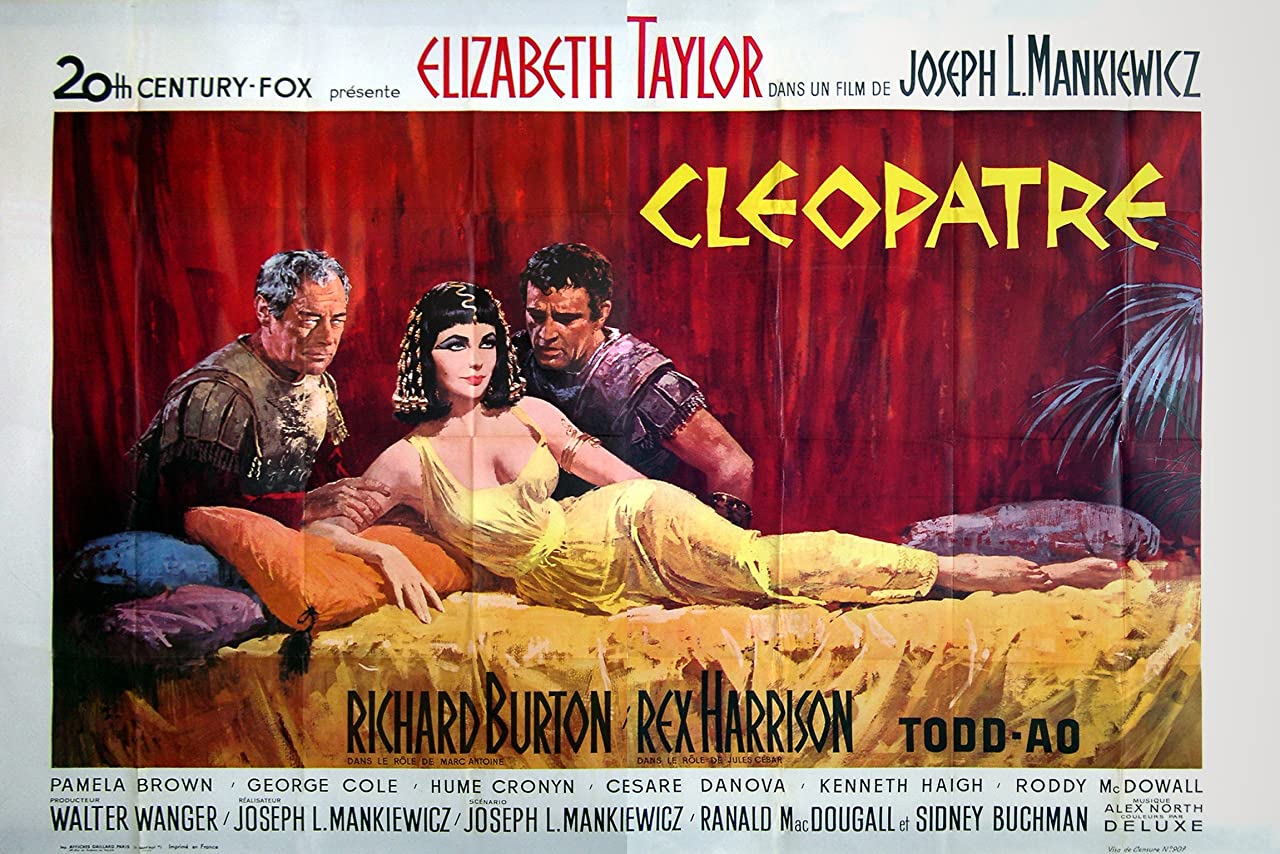

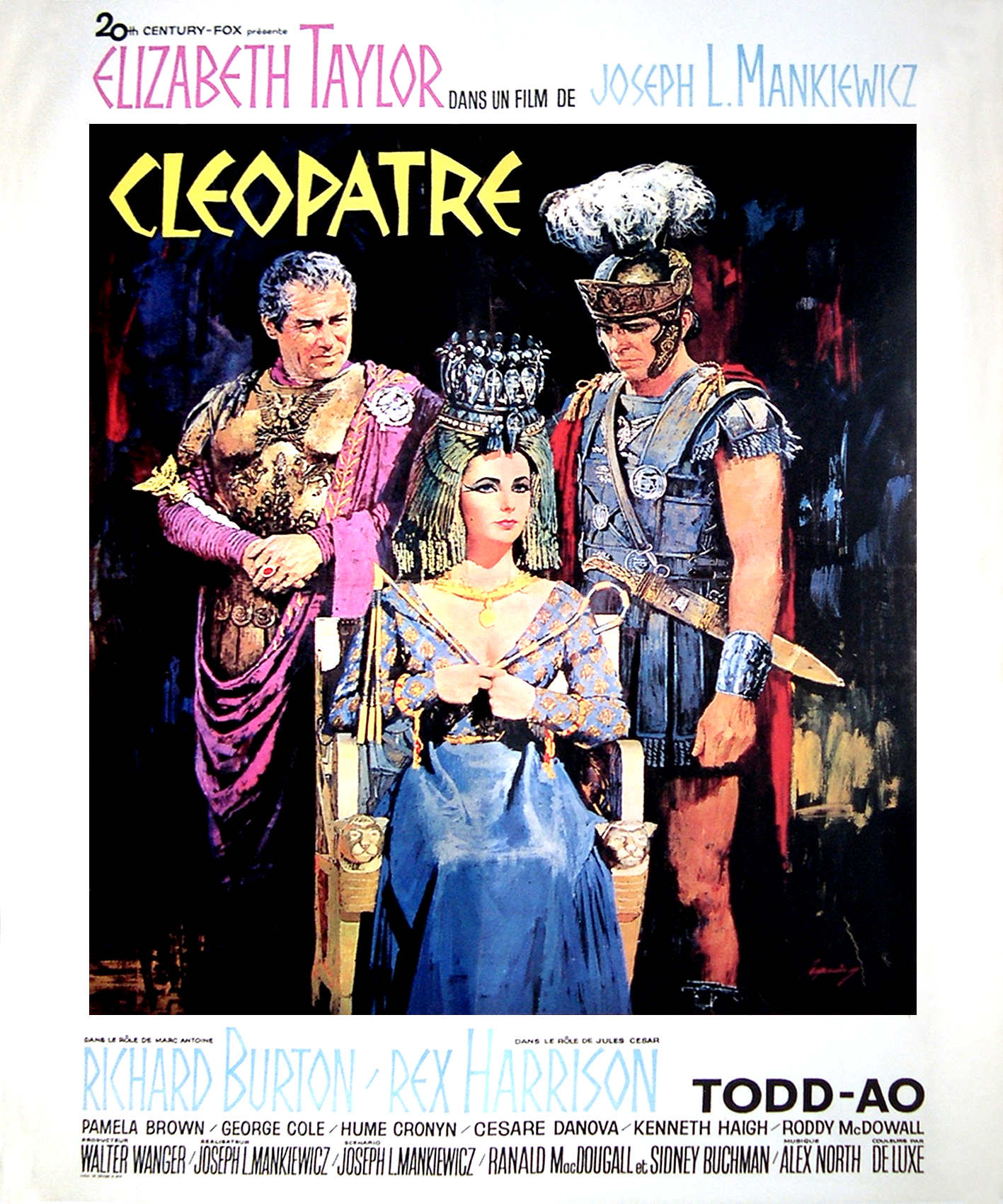

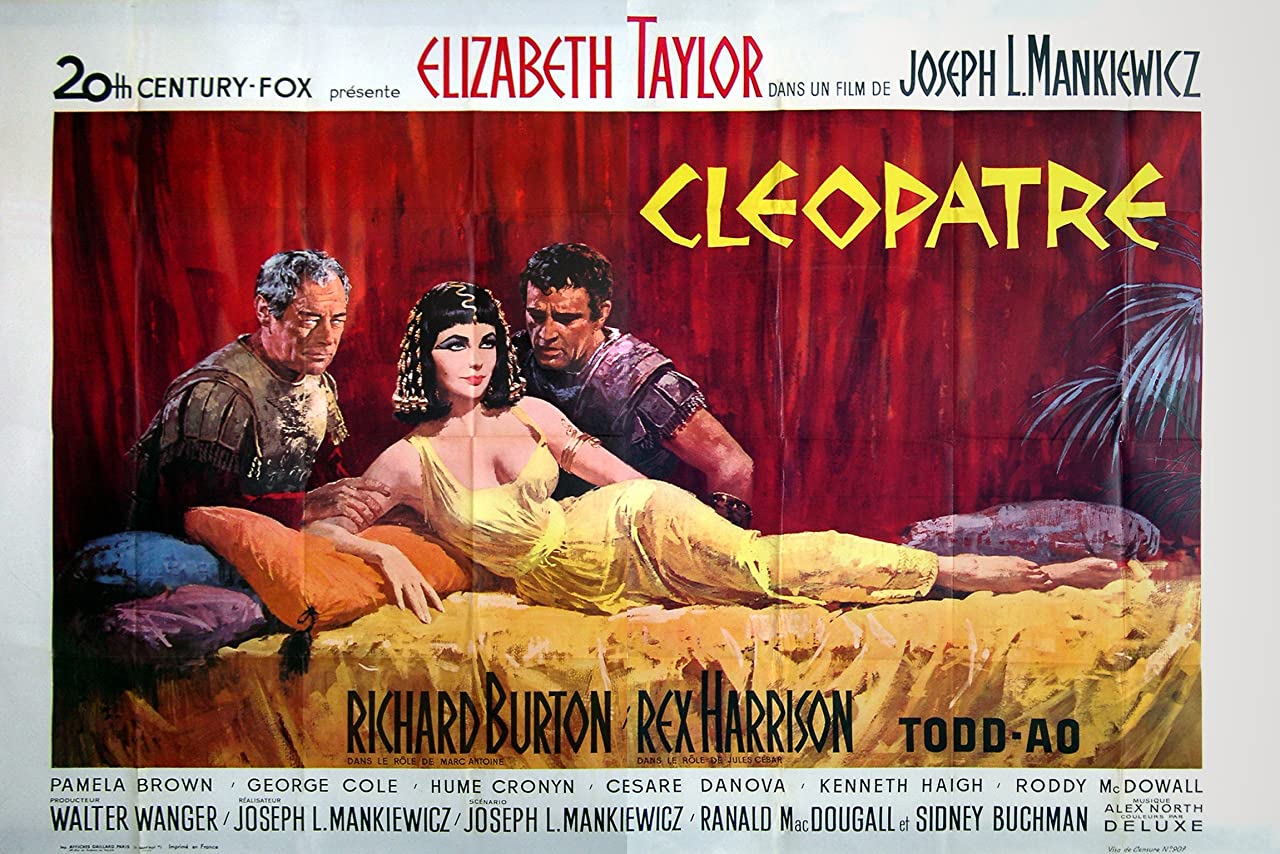

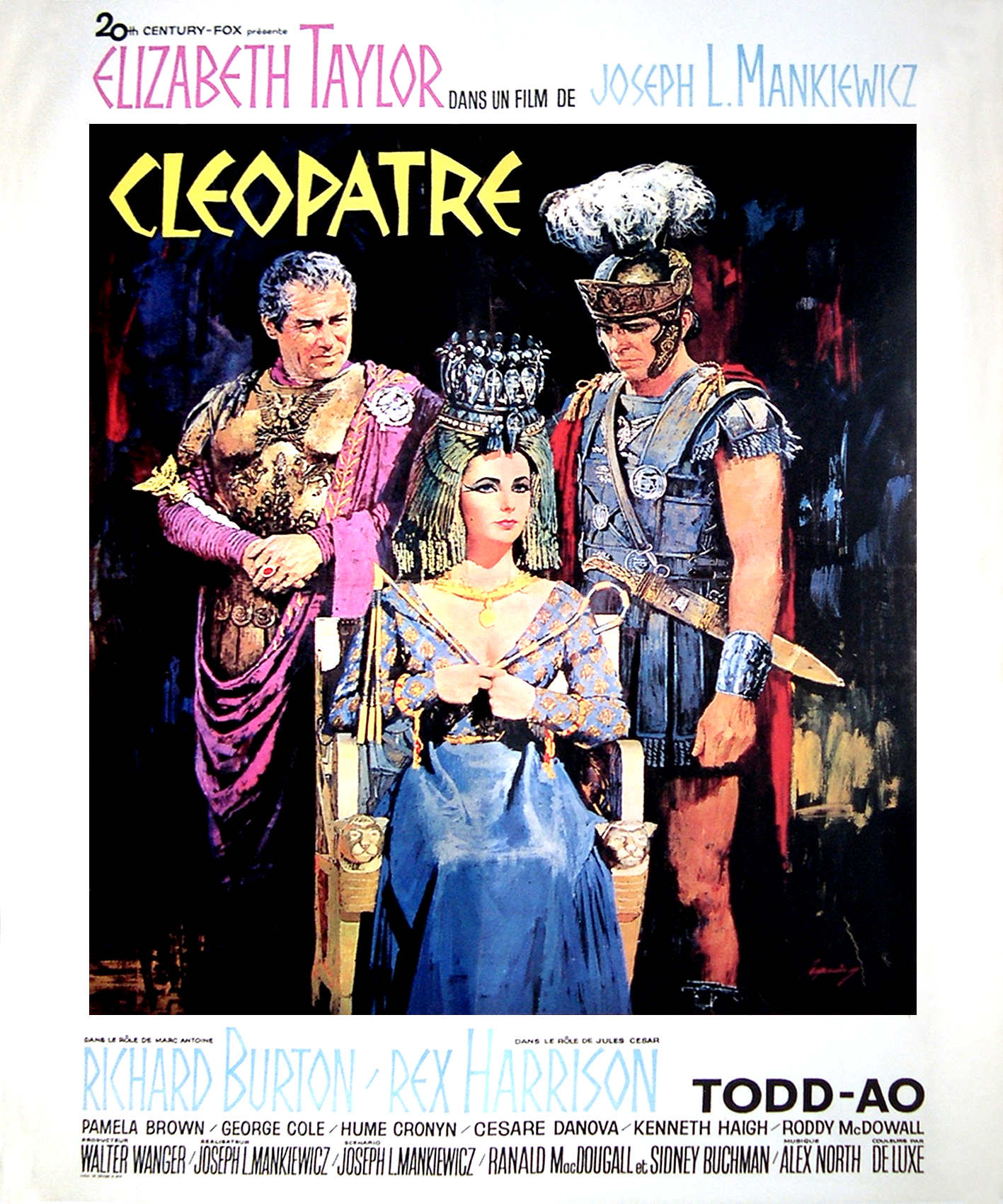

Cleopatra is a 1963 American epic historical drama film directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, with a screenplay adapted by Mankiewicz, Ranald MacDougall and Sidney Buchman from the 1957 book The Life and Times of Cleopatra by Carlo Maria Franzero, and from histories by Plutarch, Suetonius, and Appian. The film stars

Elizabeth Taylor in the eponymous role. Richard Burton, Rex Harrison, Roddy McDowall, and Martin Landau are featured in supporting roles. It chronicles the struggles of Cleopatra, the young queen of Egypt, to resist the imperial ambitions of Rome.

Viewing

the film today, one wonders at the casting, where only

Elizabeth Taylor really fits, with Richard Burton not (in

our view) making the grade. Apart from the lavish spectacle

and eye candy provided by Liz Taylor, the story is laboured.

To the point where it is a struggle to complete the movie,

without nodding off. Only the knowledge of how much it cost

and how many extras were needed, plus the incredible sets,

none of which is CGI, kept us determined to complete a

watch. More as a learning exercise. Except, as we say for

Miss Taylor, whose affair during the making of the movie,

almost led to her demise from an overdose, much as with the

real Cleopatra, when she thought she'd lost Burton's love.

Or Mark Antony likewise impaling himself, on hearing

Cleopatra was dead. It smack of Romeo &

Juliet. The

historical facts probably influencing William Shakespeare's

adaptations.

It was one of those productions in which the story about the movie proved more popular than the story in the movie.

It probably killed the old “studio system” in Hollywood. The Taylor-Burton version of “Cleopatra,” originally budgeted for $2 million, wound up costing Twentieth Century Fox $44. The studio spent two-and-a-half years producing the film, which featured lavish sets, full-scale barges, an army of “extras,” and 65 costume changes for its star, Elizabeth Taylor.

The result was an extravaganza that clocked in at six hours in the director’s cut. The studio cut the film down to four hours for the premier and three hours for theatres, which still proved a little too long for public taste, even with all the big-name stars and the gaudy staging. “Cleopatra” may have been 1963’s top grossing film, but it only recovered half of the studio’s expenses that year. Twentieth Century Fox was brought dangerously close to financial collapse that it couldn’t breath easily until 1965 when it was saved by the highly popular “Sound of Music.”

If the movie was less successful as a theatrical release, it was a stunning triumph as a tabloid sensation. The romance that sprang up between Taylor and co-star Richard Burton made “Cleopatra” the object of continual attention from the media. Writing about his work in producing the movie, Walter Wanger said “I have been told by responsible journalists there was more world interest in Cleopatra… than in any other news event of 1962”—a considerable claim in the year of the Cuban missile crisis.

Several actresses had been suggested to play the title, including Dorothy Dandridge, Joanne Woodward, Joan Collins, Marilyn Monroe, Kim Novak, Audrey Hepburn, Sophia Loren, and Susan Hayward.

But Wanger wrote that Taylor had been his only choice since the project began. And the studio’s faith in her was so great, it continued to sink millions into a picture that probably would have been cancelled if it had another leading lady.

Walter Wanger had long contemplated producing a biographical film about Cleopatra. In 1958, his production company partnered with Twentieth Century Fox to produce the film. Following an extensive casting search, Elizabeth Taylor signed on to portray the title role for a record-setting salary of $1 million. Rouben Mamoulian was hired as director, and the script underwent numerous revisions from Nigel Balchin, Dale Wasserman, Lawrence Durrell, and Nunnally Johnson. Principal photography began at Pinewood Studios on September 28, 1960, but Taylor's health problems delayed further filming. Production was suspended in November after it had gone overbudget with only ten minutes of usable footage.

When Elizabeth Taylor signed her

contract for Cleopatra she had recently become a widow, after husband number three, Michael Todd, had died in a plane crash. She was already mired in scandal though as, in her grief, just six months after her husband died, she had sought refuge in the arms of family friend Eddie Fisher – who just happened to be married to Debbie Reynolds! Public opinion turned against Elizabeth and Eddie in the most dramatic and vicious way. Ignoring the backlash, producer Walter Wagner was determined to have Elizabeth as his Queen of the

Nile. It was all systems go; Rouben Mamoulian was signed on as director, Peter Finch as Caesar and Stephen Boyd would play

Mark Antony.

A generous subsidy from the British Government led Fox to their first mistake – deciding that drizzly London’s Pinewood would be a fine substitute for sun-baked Egypt. Work began on a $600,000 set covering 20 acres, featuring imported palm trees and 52ft high sphinxes. The British weather played havoc with the sets and with Liz Taylor’s health. She called in sick on the third day of shooting and took to her hotel room for several weeks where she was attended by the best doctors and diagnosed with variously a virus, an

abscessed tooth and Malta fever!

When filming resumed after her illness, Taylor’s renegotiated contract was for 16 weeks, beginning August 1, with a guaranteed $50,000 for every additional week – they were in Italy for more than 10 months and her eventual take-home fee was $7million.

Mamoulian resigned as director, and was subsequently replaced by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, who had previously directed Taylor in Suddenly, Last Summer (1959). Production was re-located to Cinecittà, where filming resumed on September 25, 1961, without a finished shooting script. During filming, a personal scandal made worldwide headlines when it was reported that co-stars Taylor and Richard Burton had an adulterous affair. Filming wrapped on July 28, 1962, and further reshoots were made from February to March 1963. With the estimated production costs totaling $31 million, the film became the most expensive film ever made up to that point and nearly bankrupted the

studio.

Cleopatra premiered at the Rivoli Theatre in New York City on June 12, 1963. It received a generally favorable response from film

critics, and became the highest-grossing film of 1963, earning box-office receipts of $57.7 million in the United States and

Canada, and one of the highest-grossing films of the decade at a worldwide level. However, the film initially lost money because of its production and marketing costs of $44 million. It received nine nominations at the 36th Academy Awards, including for Best Picture, and won four: Best Art Direction (Color), Best Cinematography (Color), Best Visual Effects and Best Costume Design (Color).

THE

PLOT

After the

Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BC,

Julius Caesar goes to Egypt, under the pretext of being named the executor of the will of the father of the young Pharaoh Ptolemy XIII and his sister Cleopatra.

Cleopatra convinces Caesar to restore her throne from her younger brother. Caesar, in effective control of the kingdom, sentences Pothinus to death for arranging an assassination attempt on Cleopatra, and banishes Ptolemy to the eastern desert, where he and his outnumbered army would face certain death against Mithridates. Cleopatra is crowned queen of Egypt and begins to develop megalomaniacal dreams of ruling the world with Caesar, who in turn desires to become king of Rome. They marry, and when their son Caesarion is born, Caesar accepts him publicly, which becomes the talk of Rome and the Senate.

After he is made dictator for life, Caesar sends for Cleopatra. She arrives in Rome in a lavish procession and wins the adulation of the Roman people. The Senate grows increasingly discontented amid rumors that Caesar wishes to be made king, which is anathema to the Romans. On the Ides of March in 44 BC, a group of conspirators assassinate Caesar and flee the city, starting a rebellion. An alliance among Octavian (Caesar's adopted son), Mark Antony (Caesar's right-hand man and general) and Marcus Ameilius Lepidus puts down the rebellion and splits the republic.

Cleopatra is angered after Caesar's will recognizes Octavian, rather than Caesarion, as his official heir, and she returns to

Egypt.

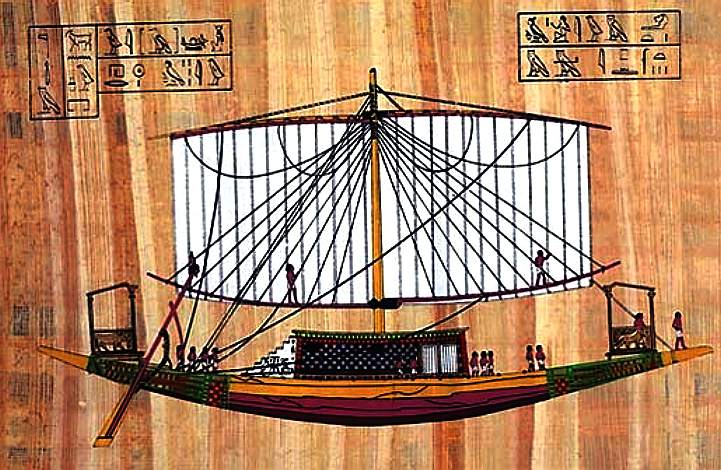

While planning a campaign against Parthia in the east, Antony realizes that he needs money and supplies that only

Egypt can sufficiently provide. After refusing several times to leave Egypt,

Cleopatra acquiesces and meets him on her royal barge in Tarsus. The two begin a love affair, and Cleopatra assures Antony that he is much more than a pale reflection of Caesar.

Octavian's removal of Lepidus forces

Marc

Antony to return to Rome, where he marries Octavian's sister Octavia to prevent political conflict. This upsets and enrages Cleopatra. Antony and Cleopatra reconcile and marry, with Antony divorcing Octavia. Octavian, incensed, reads Antony's will to the Roman senate, revealing that Antony wishes to be buried in Egypt. Rome turns against Antony, and

Octavian's call for war against Egypt receives a rapturous response. The war is decided at the naval

Battle of Actium on September 2, 31 BC, where Octavian's fleet, under the command of Agrippa, defeats the lead ships of the Antony-Egyptian fleet. Cleopatra assumes that Antony is dead and orders the Egyptian forces home. Antony follows her, leaving the rest of his fleet leaderless and soon defeated.

Several months later, Cleopatra manages to convince Antony to resume command of his troops and fight Octavian's advancing army. However, Antony's soldiers abandon him during the night. Rufio, the last man loyal to Antony, kills himself. Antony tries to goad

Octavian into single combat, but is finally forced to flee into the city. When Antony returns to the palace, Apollodorus, not believing that Antony is worthy of his queen, tells him that she is dead and Antony falls on his own sword. Apollodorus then confesses that he misled Antony and assists him to the tomb where

Cleopatra and two servants have taken refuge.

Antony dies in Cleopatra's arms.

Octavian and his army march into Alexandria with Caesarion's dead body in a wagon. He discovers the dead body of Apollodorus, who had poisoned himself. Octavian receives word that Antony is dead and that Cleopatra is holed up in a tomb. There he offers to allow her to rule Egypt as a

Roman province if she will accompany him to Rome. Cleopatra, knowing that her son is dead, agrees to Octavian's terms, including an empty pledge on the life of her son not to harm herself. After Octavian departs, she orders her servants in coded language to assist with her suicide. Octavian discovers that she is going to kill herself and he and his guards burst into

Cleopatra's chamber and find her

dead, dressed in gold, along with her servants and the asp that killed her.

THE

CAST

- Elizabeth Taylor as Cleopatra

- Richard Burton as Mark Antony

- Rex Harrison as Julius Caesar

- Pamela Brown as the High Priestess

- George Cole as Flavius

- Hume Cronyn as Sosigenes

- Cesare Danova as Apollodorus

- Kenneth Haigh as Brutus

- Andrew Keir as Agrippa

- Martin Landau as Rufio

- Roddy McDowall as Octavian

- Robert Stephens as Germanicus

- Francesca Annis as Eiras

- Grégoire Aslan as Pothinus

- Martin Benson as Ramos

- Herbert Berghof as Theodotus of Chios

- John Cairney as Phoebus

- Jacqui Chan as Lotos

- Isabelle Cooley as Charmian

- John Doucette as Achillas

- Andrew Faulds as Canidius

- Michael Gwynn as Cimber

- Michael Hordern as Cicero

- John Hoyt as Cassius

- Marne Maitland as Euphranor

- Carroll O'Connor as Servilius Casca

- Richard O'Sullivan as Pharaoh Ptolemy XIII

- Gwen Watford as Calpurnia

- Douglas Wilmer as Decimus

- Marina Berti as Queen at Tarsus

- John Karlsen as High Priest

- Loris Loddi as Caesarion, age 4

- Jean Marsh as Octavia the Younger

- Gin Mart as Marcellus

- Furio Meniconi as Mithridates II of the Bosporus

- Del Russell as Caesarion, age 7

- Kenneth Nash as Caesarion, age 12

- John Valva as Valvus

- Finlay Currie as Titus

- Laurence Naismith as Archesilius

THE LEGEND OF LOVE & LOYALTY

- The death of Cleopatra, the last ruler of Ptolemaic Egypt, has been a subject of historical debate and artistic fascination for centuries. According to the most widely accepted account, based on ancient sources such as Plutarch and Cassius Dio, Cleopatra committed suicide by allowing an asp, a venomous snake, to bite her in August 30 B.C. She chose this method of ending her life after her lover and ally, Mark Antony, had already killed himself upon hearing the false news of her death. Antony and Cleopatra had fought against Octavian, the future first emperor of Rome, in a civil war that culminated in the naval Battle of Actium, where they suffered a decisive defeat. Octavian then pursued them to Egypt, hoping to capture Cleopatra alive and display her as a trophy in his triumphal procession in Rome. However, Cleopatra resisted his attempts to negotiate with her and locked herself in a mausoleum with her loyal servants.

She sent a message to Antony, who was in another part of the city, that she was dead. Antony, who had lost all hope and did not want to live as a prisoner of Octavian, fell on his sword and mortally wounded himself. He was brought to Cleopatra's mausoleum by his soldiers and died in her arms. Cleopatra then tried to negotiate with Octavian through his messenger, but realized that he intended to humiliate her and undermine her legacy. She also feared that he would kill her son Caesarion, whom she claimed was the offspring of Julius Caesar. She decided to follow Antony's example and end her own life in a dignified manner. She dressed herself in her royal robes and lay down on a golden couch. She had previously arranged for a basket of figs to be brought to her, concealing an asp among the fruits. She let the snake bite her on the arm, or according to some accounts, on the breast. She died soon after, along with two of her female attendants who had also been bitten. Octavian's soldiers broke into the mausoleum and found her body. Octavian admired her beauty and courage, and ordered that she be buried next to Antony. He also spared her children by Antony, but killed Caesarion to eliminate any threat to his rule.

20TH CENTURY WAS ALMOST OUT-FOXED BY THEIR ICONIC BLOCKBUSTER: CLEOPATRA

20th Century Fox's Egyptian spectacle made its mark on film history for many reasons – one of which was the production's vast over-expenditure which nearly bankrupted the film corporation. Indeed, they were saved only by

the Sound of

Music's success two years later.

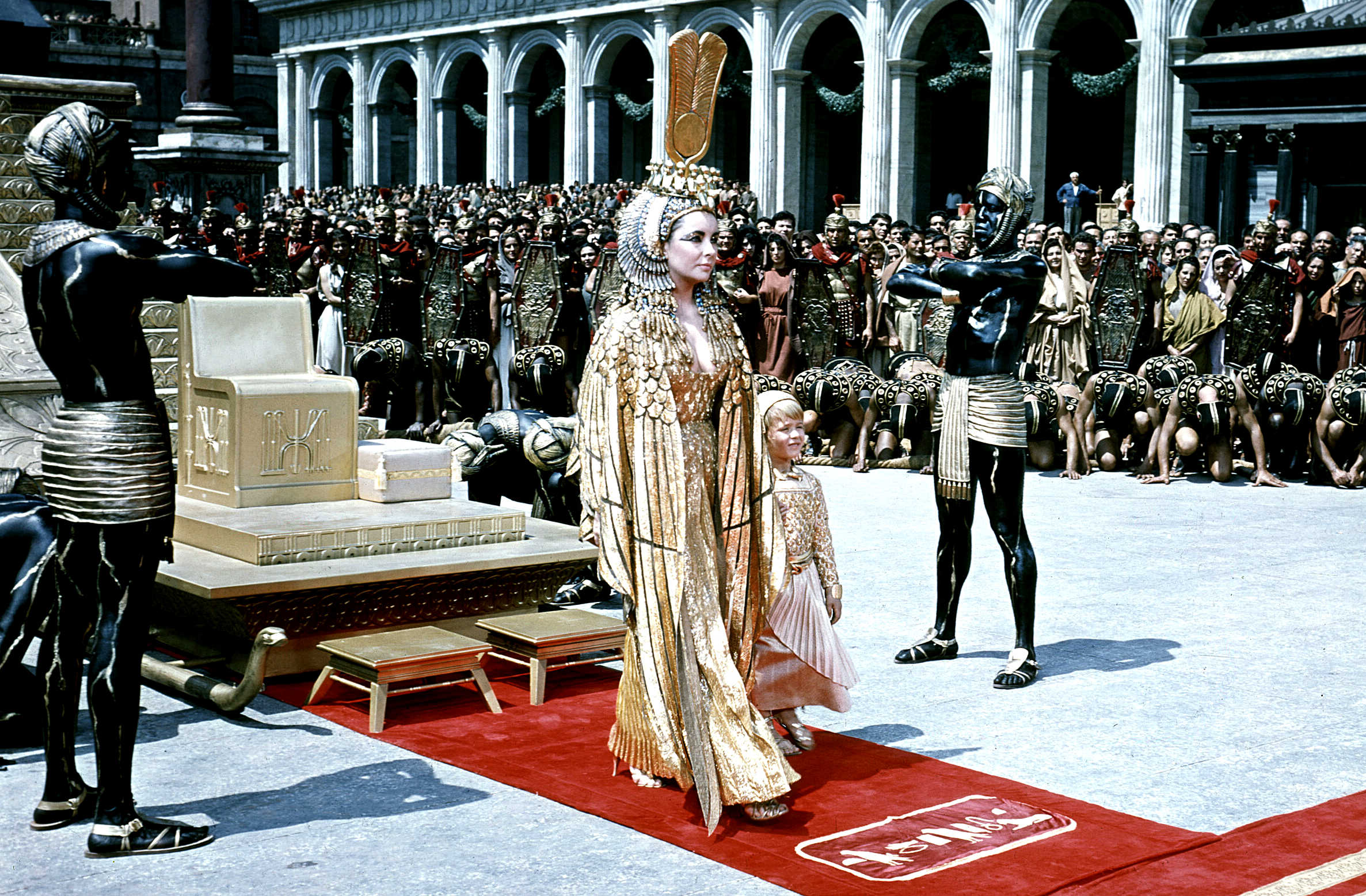

Aside from the couple's smoldering chemistry, it is the film's startling visuals that stick most memorably in one's mind; in particular the breathtakingly sumptuous costumes, which saw Taylor dripping with ornate jewellery and draped in chiffon and silks of vibrant hues – not to mention the famed 24-carat

gold cape.

Here are the top ten facts behind the stunning Cleopatra wardrobe:

1. Taylor’s 24-carat gold cloth cape, designed to look like the wings of a phoenix, was intricately assembled from thin strips of

gold leather and embellished with thousands of seed beads, bugle beads and bead-anchored sequins.

2. A colossal total of 26,000 costumes were created for the film.

3. Taylor had 65 costume changes in Cleopatra, a record for a motion picture at the time.

4. She was allocated an incredible $194,800 (£123,000) wardrobe budget.

5. Costume designer Renie Conley won the 1963 Academy Award for Best Costume Design (along with Irene Sharaff and Vittorio Nino Novarese), for her creation of Taylor's stunning gowns, which placed emphasis on the actress’ beauty and sexuality over historical accuracy.

6. Sartorially, the film was extremely influential, popularising snake rings, arm cuffs, geometric haircuts and maxi dresses, as well as the “Cleopatra Eye” makeup trend – a 60s Revlon commercial promoted Cleopatra “Sphinx Eyes”.

7. According to Rex Harrison's autobiography, Fox custom-made the boots for his character

Julius Caesar while Richard Burton's boots were Stephen Boyd hand-me-downs from the previous attempt at making the film. Harrison was amazed that Burton did not complain.

8. The armies of extras alone were issued 8,000 pairs of shoes.

9. Taylor's iconic gold cape sold at auction for $59,375 in 2012. Prior to that it had been stored in a cedar closet, finely wrapped in tissue paper.

10. The female extras complained about their overly tight and revealing costumes, which they said provoked wandering fingers among the male ensemble. The studio eventually hired a special guard to protect them.

The 1963 film Cleopatra is an American epic historical drama film directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, with a screenplay adapted from the 1957 book The Life and Times of Cleopatra by Carlo Maria Franzero, and from histories by Plutarch, Suetonius, and Appian1. The film stars Elizabeth Taylor in the eponymous role, Richard Burton as Mark Antony, Rex Harrison as Julius Caesar, Roddy McDowall as Octavian, and Martin Landau as Rufio. It chronicles the struggles of Cleopatra, the young queen of Egypt, to resist the imperial ambitions of Rome, and her romantic and political alliances with Caesar and Antony.

The film is famous for its production troubles, which included multiple script revisions, director changes, cast changes, health problems, budget overruns, location changes, and a scandalous affair between Taylor and Burton123. The film was originally planned to be a two-part release, with a total running time of over six hours, but was cut down to four hours for its theatrical release. The film was the most expensive film ever made up to that point, costing $31 million (not counting the $5 million spent on the aborted British shoot), and nearly bankrupted the studio. The film received mixed reviews from critics, but was a box office success, earning $57.8 million in the US and Canada, and $40.3 million in worldwide theatrical rental1. The film won four Academy Awards for Best Art Direction-Set Decoration (Color), Best Cinematography (Color), Best Costume Design (Color), and Best Visual Effects, and was nominated for five more. The film is considered a classic of Hollywood cinema, and has influenced many other films and television shows about ancient Egypt.

THE SCANDAL

Elizabeth and Richard didn’t begin working together until January 1962. Before they met, Liz had worried that Burton would look down on her for her lack of theatrical training but when he turned up on set his first words to Elizabeth were, “Has anyone ever told you you’re a pretty girl?” Added to that he was so hungover that Liz found herself steadying his trembling hands and she took pity on him. “For the first scene, there was no dialogue – we had to just look at each other,” said Taylor. “And that… was it!”

Burton was an inveterate womanizer; he’d had numerous affairs but always returned to his wife Sybil. Everyone assumed this dalliance between him and Liz would be just as short-lived and that it would simply blow over. By February rumours of the affair had gone worldwide and Sybil Burton and Eddie Fisher couldn’t ignore them any more – they both fled Rome in the hope of forcing the couple apart. It worked! Richard broke it off with Liz and released a statement saying he had no intention of leaving Sybil. But no one was fooled (apart from Liz, briefly, who reacted by taking too many sedatives and ended up in hospital again).

As soon as they resumed filming the chemistry between them was too much. “I feel as if I’m intruding,” Mankiewicz said one day as his shouts of “Cut!” went unnoticed by Taylor and Burton during a love scene. But the explosive and passionate on-off nature of their relationship was not conducive to a smooth filming schedule – they drank heavily, turned up late (or not at all) and fought frequently.

The press carried daily updates on the Taylor-Burton affair with paparazzi stalking their every move and whipped everyone up into a frenzy. A congresswoman from Georgia called on the attorney general to prevent the pair from re-entering the country, on the grounds of ‘undesirability’ and even the

Catholic church weighed in publicly

criticizing them.

Incredible

sets, at incredible prices

A

staggering extras ensemble, with attendant high costs

Not

acting, they really were in love.

In

our view, weak casting, but then, you have to work with the

talent of the day

PRODUCTION

Walter Wanger had long desired to produce a biographical film about Cleopatra. As an undergraduate at Dartmouth College, he first read Théophile Gautier's fantasy novel One of Cleopatra's Nights and Other Fantastic Romances and then Thomas North's 1579 English translation of Plutarch's Lives and

William

Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra. Wanger had envisioned Cleopatra as "the quintessence of youthful femininity, of womanliness and strength," but it was not until he watched Elizabeth Taylor in A Place in the Sun (1951) that he found his ideal candidate for the role. Around this time, Wanger had discovered through a private detective that his wife, Joan Bennett, was having an affair with her talent agent Jennings Lang. On the afternoon of December 13, 1951, Wanger shot Lang twice after having spotted him with Bennett in a parking lot near MCA. Lang survived, and Wanger, pleading insanity, served four months in prison at the Castaic Honor Farm, north of Los Angeles.

Following his release, Wanger had achieved a career comeback, having produced Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) and I Want to Live! (1958), in which Susan Hayward won the Academy Award for Best Actress. He would soon return to his dream project of a Cleopatra biographical film.

DEVELOPMENT

Wanger pitched the idea to various film studios, including Monogram and RKO Pictures. He also approached Taylor and her husband Michael Todd about producing the project with United Artists. Taylor expressed interest in the project but delegated the decision to Todd. Meanwhile, Twentieth Century Fox was in financial trouble following its severe box office losses of The Barbarian and the Geisha, A Certain Smile and The Roots of Heaven, all released in 1958. To reverse the studio's fortunes, studio president Spyros Skouras requested that studio executive David Brown find a viable project that would be a "big picture." Brown suggested a remake of Cleopatra (1917), which had starred Theda Bara.

In the fall of 1958, Wanger's production company entered into a coproduction agreement with Twentieth Century Fox. Wanger pitched four

properties - Cleopatra, Justine, The Dud Avocado, and The

Fall - for the executives to consider. They selected the first three, and Cleopatra would be the first to enter into production. On September 15, Wanger purchased the screen rights to Carlo Mario Franzero's biography The Life and Times of Cleopatra. On September 30, Skouras held his first meeting with Wanger, and asked his secretary to retrieve the screenplay for the 1917 version of Cleopatra. Skouras insisted, "All this needs is a little rewriting. Just give me this over again and we'll make a lot of money." Because the original screenplay had been written for a silent film, the script mostly contained instructions for camera setups.

In December 1958, Ludi Claire, a writer and former actress, was hired to write a rough draft of the script. That same month, art director John DeCuir was hired to produce conceptual artwork to illustrate the visual scale of the project. In March 1959, English author Nigel Balchin was hired to write another script draft. Meanwhile, Wanger had approached Alfred Hitchcock to direct the film, having worked with him on Foreign Correspondent (1940), but Hitchcock declined. Skouras then selected Rouben Mamoulian, who had worked with Wanger on Applause (1929), to direct. With Mamoulian as director, Balchin's script pleased neither him nor Taylor, who felt that the first act was forced and that Cleopatra lacked sufficient characterization. Based on his recently aired I, Don Quixote episode in the CBS anthology series DuPont Show of the Month, Dale Wasserman was selected to complete the final draft. Wanger instructed him to focus all attention on Cleopatra as the central role. Wasserman recounted that he had never met Taylor, so he watched her earlier films to better acquaint himself with her acting style. In the spring of 1960, English novelist Lawrence Durrell was hired to rewrite the script.

CASTING

At a meeting, in October 1958, production head Buddy Adler favored a relatively cheap production of $2 million, with one of Fox's contract actresses, such as Joan Collins (who tested extensively for the part), Joanne Woodward or model Suzy Parker, in the title role. Wanger protested, envisioning a much more opulent epic with a voluptuous actress as Cleopatra. Wanger suggested Susan Hayward while Audrey Hepburn, Sophia Loren, and Gina Lollobrigida were also under consideration. When Mamoulian was hired to direct, he had offered the title role to Dorothy Dandridge, an African American, during a lunch meeting at the Romanoff's restaurant in Beverly Hills. Dandridge replied, "You won't have the guts to go through with this... They are going to talk you out of it."

In September 1959, Wanger contacted Taylor again on the set of Suddenly, Last Summer (1959), and Taylor asked for a record-setting contract of $1 million ($10

million in 2022) plus ten percent of the box-office gross. On October 15, a contract-signing event was staged inside Adler's office where Taylor signed blank papers because the real contract would not be ready for months. Wanger had considered Laurence Olivier and Rex Harrison for the role of

Julius

Caesar, and Richard Burton for Mark Antony. However, the studios refused to approve Harrison and Burton. On July 28, 1960, Taylor signed a real contract. It was also stipulated that the film would be shot in

Europe and in the Todd-AO format, developed by Taylor's late husband Mike Todd, which ensured that Taylor would receive additional royalties.

In January 1960, Stephen Boyd was approached by Wanger about being cast as Mark Antony, but felt he was too young for the role. In August 1960, Boyd was cast as Mark Antony, Peter Finch as Julius Caesar and Keith Baxter as Octavian. Mamoulian had also cast Elisabeth Welch to portray one of Cleopatra's handmaidens.

CRITICS & BOX OFFICE

Bosley Crowther of The New York Times called Cleopatra "one of the great epic films of our day," crediting Mankiewicz for "his fabrication of characters of colorfulness and depth, who stand forth as thinking, throbbing people against a background of splendid spectacle, that gives vitality to this picture and is the key to its success." Vincent Canby, reviewing for Variety, wrote that Cleopatra is "not only a supercolossal eye-filler (the unprecedented budget shows in the physical opulence throughout), but it is also a remarkably literate cinematic recreation of an historic epoch." For the Los Angeles Times, Philip K. Scheuer felt Cleopatra was "a surpassingly beautiful film and a drama that need not hide its literate, intelligent face because it happens to have been written, not by Shakespeare or Shaw, but by three fellows named Joseph L. Mankiewicz, who also directed it, Ranald MacDougall and Sidney Buchman. These are, at any rate, the names on the screen credits, and they have done their job with integrity."

Time magazine harshly wrote: "As drama and as cinema, Cleopatra is riddled with flaws. It lacks style both in image and in action. Never for an instant does it whirl along on wings of epic elan; generally it just bumps from scene to ponderous scene on the square wheels of exposition." James Powers of The Hollywood Reporter wrote "Cleopatra is not a great movie. But it is primarily a vast, popular entertainment that sidesteps total greatness for broader appeal. This is not an adverse criticism, but a notation of achievement." Claudia Cassidy of the Chicago Tribune summarized Cleopatra as a "huge and disappointing film." Of the cast, she lauded "Rex Harrison's brilliantly quizzical Caesar, the best written role in Joseph Mankiewicz's erratic script, and haunted by Richard Burton's tragic Marc Antony, an actor's triumph over a writer's mediocrity. And with a prodigal gesture of futility, all of it is focused on Elizabeth Taylor, hopelessly out of her depth as a fishwife Cleopatra."

Penelope Houston, reviewing for Sight & Sound, acknowledged that Mankiewicz tried "to make this a film about people and their emotions rather than a series of sideshows. But for this ambition to hold up, over the film's great footage, he needed a visual style which would be more than merely illustrative, dialogue really worth speaking, and actors altogether more persuasive. As the sets seem to grow bigger and bigger, so progressively the actors dwindle." Judith Crist, in her review for the New York Herald Tribune, concurred: "So grand and grandiose are the sets that the characters are dwarfed, and so wide is his screen that this concentration on character results in a strangely static epic in which the overblown close-ups are interrupted at best by a pageant or dance, more often by unexciting bits and pieces of exits, entrances, marches or battles." Even Elizabeth Taylor found it wanting, saying, "They had cut out the heart, the essence, the motivations, the very core, and tacked on all those battle scenes. It should have been about three large people, but it lacked reality and passion. I found it vulgar."

The New York Times estimated that 80% of reviews in the United States were favorable but only 20% of reviews in Europe were positive. American film critic Emanuel Levy wrote retrospectively: "Much maligned for various reasons, [...] Cleopatra may be the most expensive movie ever made, but certainly not the worst, just a verbose, muddled affair that is not even entertaining as a star vehicle for Taylor and Burton." Billy Mowbray of British television channel Film4 remarked that the film is "giant of a movie that is sometimes lumbering, but ever watchable thanks to its uninhibited ambition, size and glamour."

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 56% of 41 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 5.9/10. The website's consensus reads: "Cleopatra is a lush, ostentatious, endlessly eye-popping epic that sags [and] collapses from a (and how could it not?) four-hour runtime." Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 60 out of 100, based on 14 critics, indicating "mixed or average" reviews.

Box office

Three weeks into its theatrical release, Cleopatra became the number-one box office film in the United States, grossing $725,000 in 17 key cities. It held the top position for the next twelve weeks before being dethroned by The V.I.P.s, which also starred Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. It recaptured the number-one spot three weeks later, and proved to be the highest-grossing film of 1963. By January 1964, the film had earned $15.7 million in distributor rentals from 55 theaters in the United States and Canada. It finished its box-office run with $26 million in rentals in the United States and Canada. The film was also a major hit in

Italy, where it sold 10.9 million tickets. It sold a further 5.4 million tickets in

France and

Germany, and 32.9 million tickets in the

Soviet Union when it was released there in 1978.

By March 1966, Cleopatra had earned worldwide rentals of $38.04 million, leaving it $3 million short of breaking even. Fox eventually recouped its investment that same year when it sold the television broadcast rights to ABC for $5 million, a then-record amount paid for a single film. The film ultimately earned $40.3 million in worldwide rentals from its theatrical run.

CLEOPATRA

THE MUMMY - CLEOPATRA'S MUMMY

'Cleopatra

- The Mummy (Reborn)' followed 'Kulo-Luna'

in the development sequence, though may not be the first to

see the light of day as a movie, comic or anime.

Kulo-Luna was

the first of the John Storm franchise (for which a 1st draft

script is published). Kulo-Luna could be the sequel to

'Cleopatra

The Mummy' or the other way around. The John Storm

franchise is a series of

ocean awareness adventures, featuring the incredible Egypt

inspired, solar

powered trimaran: Elizabeth

Swann. Also under development are, 'Treasure

Island: Blackbeard's Curse & Pirates Gold (and Operation

Neptune: The Lost City of Atlantis. There are four versions of 'Cleopatra,'

each coming from a different angle, but all including

replication, as a modern means to reincarnate the long dead

Egyptian queen.