The Nile crocodile is presently the most common crocodilian in Africa. Among crocodilians today, only the saltwater crocodile occurs over a broader geographic area, although other species, especially the spectacled caiman (Caiman crocodilus) (due to its small size and extreme adaptability in habitat and flexibility in diet), seem to actually be more abundant. This species’ historic range, however, was even wider. They were found as far north as the

Mediterranean coast in Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, the Nile Delta of Egypt and across the

Red Sea in Palestine and Syria. The Nile crocodile has historically been recorded in areas where they are now regionally extinct. For example, Herodotus recorded the species inhabiting Lake Moeris in Egypt. They are thought to have become extinct in the Seychelles in the early 19th century (1810–1820). Today, Nile crocodiles are widely found in, among others, Somalia, Ethiopia, Uganda, Kenya, Egypt, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Gabon, Angola,

South

Africa, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Sudan, South Sudan, Botswana, and Cameroon. The Nile crocodile's current range of distribution extends from the regional tributaries of the Nile in Sudan and Lake Nasser in Egypt to the Cunene river of Angola, the Okavango Delta of Botswana, and the Olifants River in South Africa.

Isolated populations also exist in Madagascar, which were supposed to have likely colonized the island very recently, after the extinction of the endemic crocodile Voay within the last 2000

years. However in 2022 a skull of Crocodylus from Madagascar was found to be around 7,500 years old based on radiocarbon dating, suggesting that the extinction of Voay post-dates the arrival of Nile crocodiles on Madagascar. Nile Crocodiles occur in the western and southern parts of Madagascar from Sambirano to Tôlanaro. They have been spotted in Zanzibar and the Comoros in modern times, but occur very rarely.

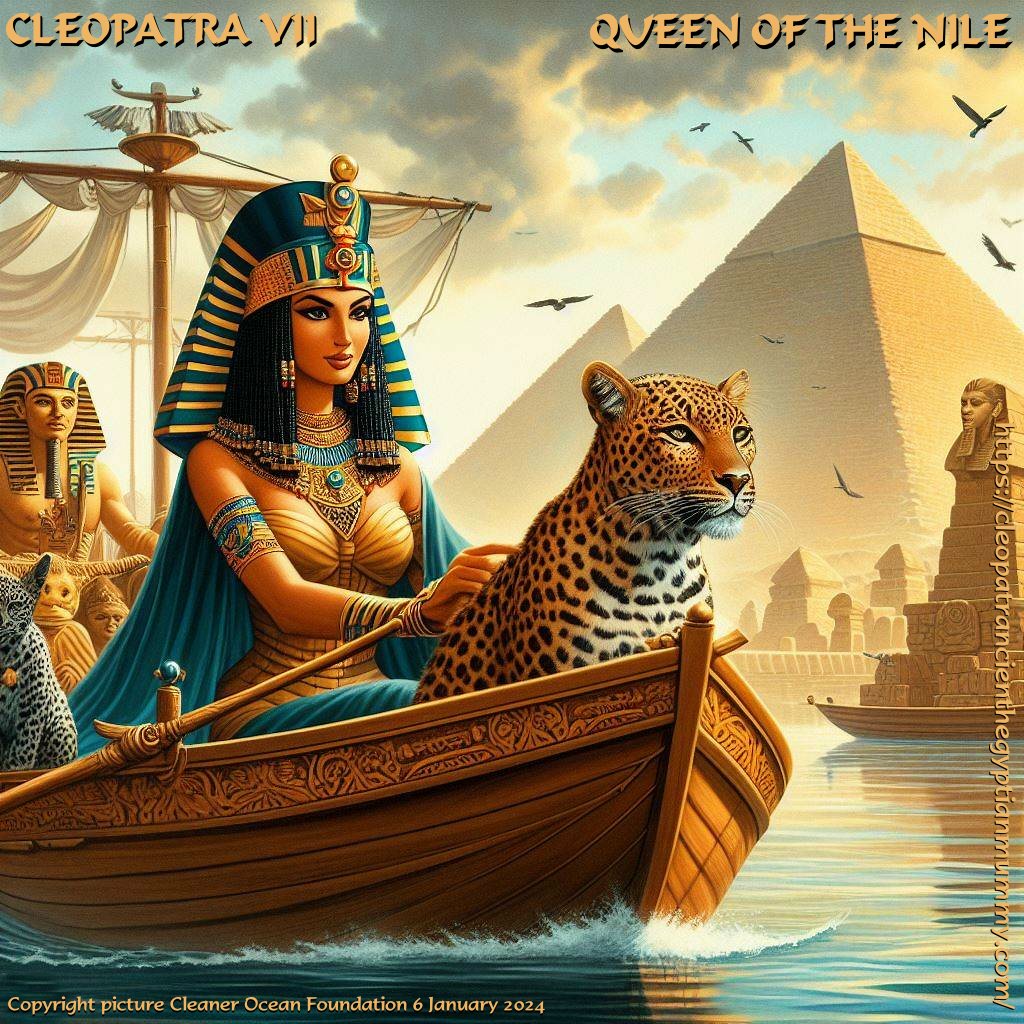

Cleopatra

loved her Nile crocodiles. They were a scene along the banks

of her favorite river. And a source of fascination for

visitors to Egypt, as she sailed her barges along the sacred

waterway to entertain her Roman Guests. They are mentioned

in William Shakespeare's play; Antony

and Cleopatra first performed at the Globe Theatre in

1607.

The species was previously thought to extend in range into the whole of West and Central Africa, but these populations are now typically recognized as a distinct species, the West African (or desert) crocodile. The distributional boundaries between these species were poorly understood, but following several studies, they are now better known. West African crocodiles are found throughout much of West and Central Africa, ranging east to South Sudan and Uganda where the species may come into contact with the Nile crocodile. Nile crocodiles are absent from most of West and Central Africa, but range into the latter region in eastern and southern Democratic Republic of Congo, and along the Central African coastal

Atlantic region (as far north to Cameroon). Likely a level of habitat segregation occurs between the two species, but this remains to be confirmed.

Nile crocodiles may be able to tolerate an extremely broad range of habitat types, including small brackish streams, fast-flowing rivers, swamps, dams, and tidal lakes and estuaries. In East Africa, they are found mostly in rivers, lakes, marshes, and dams, favoring open, broad bodies of water over smaller ones. They are often found in waters adjacent to various open habitats such as savanna or even semi-desert but can also acclimate to well-wooded swamps, extensively wooded riparian zones, waterways of other woodlands and the perimeter of forests. In Madagascar, the remnant population of Nile crocodiles has adapted to living within caves. Nile crocodiles may make use of ephemeral watering holes on occasion. Although not a regular sea-going species as is the American crocodile, and especially the saltwater crocodile, the Nile crocodile possesses salt glands like all true crocodiles (i.e., excluding alligators and caimans), and does on occasion enter coastal and even marine waters. They have been known to enter the sea in some areas, with one specimen having been recorded 11 km (6.8 mi) off St. Lucia Bay in 1917.

Cleopatra

was fond of entertaining dignitaries on her royal barges as

they cruise the Nile, such as Julius

Caesar and Mark

Antony. Crocodiles would feature in the entertainments,

and some were virtual pets, alongside cheetahs

and leopards.

Nile crocodiles are apex predators throughout their range. In the water, this species is an agile and rapid hunter relying on both movement and pressure sensors to catch any prey unfortunate enough to present itself inside or near the waterfront. Out of water, however, the Nile crocodile can only rely on its limbs, as it gallops on solid ground, to chase prey. No matter where they attack prey, this and other crocodilians take practically all of their food by ambush, needing to grab their prey in a matter of seconds to succeed. They have an ectothermic metabolism, so can survive for long periods between meals. However, for such large animals, their stomachs are relatively small, not much larger than a basketball in an average-sized adult, so as a rule, they are anything but voracious eaters. Young crocodiles feed more actively than their elders, according to studies in Uganda and Zambia. In general, at the smallest sizes (0.3–1 m (1 ft 0 in – 3 ft 3 in)), Nile crocodiles were most likely to have full stomachs (17.4% full per Cott); adults at 3–4 m (9 ft 10 in – 13 ft 1 in) in length were most likely to have empty stomachs (20.2%). In the largest size range studied by Cott, 4–5 m (13 ft 1 in – 16 ft 5 in), they were the second most likely to either have full stomachs (10%) or empty stomachs

(20%). Other studies have also shown a large number of adult Nile crocodiles with empty stomachs. For example, in Lake Turkana, Kenya, 48.4% of crocodiles had empty stomachs. The stomachs of brooding females are always empty, meaning that they can survive several months without food.

The Nile crocodile mostly hunts within the confines of waterways, attacking aquatic prey or terrestrial animals when they come to the water to drink or to cross. The crocodile mainly hunts land animals by almost fully submerging its body under water. Occasionally, a crocodile quietly surfaces so that only its eyes (to check positioning) and nostrils are visible, and swims quietly and stealthily toward its mark. The attack is sudden and unpredictable. The crocodile lunges its body out of water and grasps its prey. On other occasions, more of its head and upper body is visible, especially when the terrestrial prey animal is on higher ground, to get a sense of the direction of the prey item at the top of an embankment or on a tree branch. Crocodile teeth are not used for tearing up flesh, but to sink deep into it and hold on to the prey item. The immense bite force, which may be as high as 5,000 lbf (22,000 N) in large adults, ensures that the prey item cannot escape the grip. Prey taken is often much smaller than the crocodile itself, and such prey can be overpowered and swallowed with ease. When it comes to larger prey, success depends on the crocodile's body power and weight to pull the prey item back into the water, where it is either drowned or killed by sudden thrashes of the head or by tearing it into pieces with the help of other crocodiles.

Subadult and smaller adult Nile crocodiles use their bodies and tails to herd groups of fish toward a bank, and eat them with quick sideways jerks of their heads. Some crocodiles of the species may habitually use their tails to sweep terrestrial prey off balance, sometimes forcing the prey specimen into the water, where it can be more easily drowned. They also cooperate, blocking migrating fish by forming a semicircle across the river. The most dominant crocodile eats first. Their ability to lie concealed with most of their bodies under

water, combined with their speed over short distances, makes them effective opportunistic hunters of larger prey.

Crocodiles

do not make good eating. Alligators in America are much more

palatable. Though reptiles are a source of fascination,

being almost unchanged through prehistoric times.

They grab such prey in their powerful jaws, drag it into the water, and hold it underneath until it drowns. They also scavenge or steal kills from other predators, such as lions and leopards (Panthera pardus). Groups of Nile crocodiles may travel hundreds of meters from a waterway to feast on a carcass. They also feed on dead hippopotamuses (Hippopotamus amphibius) as a group (sometimes including three or four dozen crocodiles), tolerating each other. Much of the food from crocodile stomachs may come from scavenging carrion, and the crocodiles could be viewed as performing a similar function at times as do vultures or hyenas on land. Once their prey is dead, they rip off and swallow chunks of flesh. When groups are sharing a kill, they use each other for leverage, biting down hard and then twisting their bodies to tear off large pieces of meat in a "death roll". They may also get the necessary leverage by lodging their prey under branches or stones, before rolling and ripping.

The Nile crocodile possesses unique predation behavior characterized by the ability of preying both within water, where it is best adapted, and out of it, which often results in unpredictable attacks on almost any other animal up to twice its size. Most hunting on land is done at night by lying in ambush near forest trails or roadsides, up to 50 m (170 ft) from the water's edge.[96] Since their speed and agility on land is rather outmatched by most terrestrial animals, they must use obscuring vegetation or terrain to have a chance of succeeding during land-based hunts. In one case, an adult crocodile charged from the water up a bank to kill a bushbuck (Tragelaphus scriptus) and instead of dragging it into the water, was observed to pull the kill further on land into the cover of the bush. Two subadult crocodiles were once seen carrying the carcass of a nyala (Tragelaphus angasii) across land in unison. In South Africa, a game warden far from water sources in a savannah-scrub area reported that he saw a crocodile jump up and grab a donkey by the neck and then drag the prey off. Small carnivores are readily taken opportunistically, including African clawless otters (Aonyx capensis).

QUEEN

OF THE NILE - A

superb depiction of Cleopatra enjoying a ride on the great river that she

loved so much, along with leopards and crocodiles. She lived at a time built

on much achieved by her forbears, coming to power at a time of change, thus

needing to use her wiles to seduce successive Roman leaders. On wonders then

at her intellectual and bedroom skills, for seducing Julius Caesar was no

easy task, but then to succeed again with Mark Antony, must surely rank her

as one of the greatest seducers of men of power, of all time. And, that sets

her apart from other female rulers, past and present. For, she managed to

pull off such alliances, despite not being facially beautiful. She must then

have possessed the body of a temptress. Which as we know, she presented

rather well. Better than all the lacey undergarments and modern attire, may achieve

today.

Conservation organizations have determined that the main threats to Nile crocodiles, in turn, are loss of habitat, pollution, hunting, and human activities such as accidental entanglement in

fishing

nets. Though the Nile crocodile has been hunted since ancient times, the advent of the readily available firearm made it much easier to kill these potentially dangerous reptiles. The species began to be hunted on a much larger scale from the 1940s to the 1960s, primarily for high-quality leather, although also for meat with its purported curative properties. The population was severely depleted, and the species faced extinction. National laws, and international trade regulations have resulted in a resurgence in many areas, and the species as a whole is no longer wholly threatened with extinction. The status of Nile crocodiles was variable based on the regional prosperity and extent of conserved wetlands by the 1970s. However, as is the case for many large animal species whether they are protected or not, persecution and poaching have continued apace and between the 1950s and 1980s, an estimated 3 million Nile crocodiles were slaughtered by humans for the leather trade. In Lake Sibaya, South Africa, it was determined that in the 21st century, persecution continues as the direct cause for the inability of Nile crocodiles to recover after the leather trade last century. Recovery for the species appears quite gradual and few areas have recovered to bear crocodile populations, i.e. largely insufficient to produce sustainable populations of young crocodiles, on par with times prior to the peak of leather trading. Crocodile 'protection programs' are artificial environments where crocodiles exist safely and without the threat of extermination from hunters.

An estimated 250,000 to 500,000 individuals occur in the wild today. The IUCN Red List assesses the Nile crocodile as "Least Concern (LR/lc)". The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) lists the Nile crocodile under Appendix I (threatened with extinction) in most of its range; and under Appendix II (not threatened, but trade must be controlled) in the remainder, which either allows ranching or sets an annual quota of skins taken from the wild. The Nile crocodile is widely distributed, with strong, documented populations in many countries in eastern and southern Africa, including Somalia, Ethiopia, Kenya, Zambia and Zimbabwe. This species is farmed for its meat and leather in some parts of Africa. Successful sustainable-yield programs focused on ranching crocodiles for their skins have been successfully implemented in this area, and even countries with quotas are moving toward ranching. In 1993, 80,000 Nile crocodile skins were produced, the majority from ranches in Zimbabwe and South Africa. Crocodile farming is one of the few burgeoning industries in Zimbabwe. Unlike American alligator flesh, Nile crocodile meat is generally considered unappetizing although edible as tribes such as the Turkana may opportunistically feed on them. According to Graham and Beard (1968), Nile crocodile meat has an "indescribable" and unpleasant taste, greasy texture and a "repellent" smell.

The conservation situation is more grim in Central and West Africa presumably for both the Nile and West African crocodiles. The crocodile population in this area is much more sparse, and has not been adequately surveyed. While the natural population in these areas may be lower due to a less-than-ideal environment and competition with sympatric slender-snouted and dwarf crocodiles, extirpation may be a serious threat in some of these areas. At some point in the 20th century, the Nile crocodile appeared to have been extirpated as a breeding species from Egypt, but has locally re-established in some areas such as the Aswan Dam.

Additional factors are a loss of wetland habitats, which is addition to direct dredging, damming and irrigation by humans, has retracted in the east, south and north of the crocodile's range, possibly in correlation with global warming. Retraction of wetlands due both to direct habitat destruction by humans and environmental factor possibly related to

global warming is perhaps linked to the extinction of Nile crocodiles in the last few centuries in Syria, Israel and Tunisia. In Lake St. Lucia, highly saline water has been pumped into the already brackish waters due to irrigation practices. Some deaths of crocodiles appeared to have been caused by this dangerous salinity, and this one-time stronghold for breeding crocodiles has experienced a major population decline. In yet another historic crocodile stronghold, the Olifants River, which flows through Kruger National Park, numerous crocodile deaths have been reported. These are officially due to unknown causes but analysis has indicated that environmental pollutants caused by humans, particularly the burgeoning coal industry, are the primary cause. Much of the contamination of crocodiles occurs when they consume fish themselves killed by pollutants. Additional ecological surveys and establishing management programs are necessary to resolve these questions.

The Nile crocodile is the top predator in its environment, and is responsible for checking the population of mesopredator species, such as the barbel catfish and lungfish, that could overeat fish populations on which other species, including birds, rely. One of the fish predators seriously affected by the unchecked mesopredator fish populations (due again to crocodile declines) is humans, particularly with respect to tilapia, an important commercial fish that has declined due to excessive

predation. The Nile crocodile also consumes dead animals that would otherwise pollute the waters.

THE

POISON ASP - Tragically, queen Cleopatra poisoned herself

with an Egyptian cobra. Later her

mausoleum was washed into the sea by an earthquake and

tsunami in 365AD. Until, Safiya

Sabuka finds her mausoleum off the coast of Alexandria

(fiction).

The Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) is a large crocodilian native to freshwater habitats in Africa, where it is present in 26 countries. It is widely distributed in sub-Saharan Africa, occurring mostly in the eastern, southern, and central regions of the continent, and lives in different types of aquatic environments such as lakes, rivers, swamps and marshlands. It occasionally inhabits deltas, brackish lakes and rarely also saltwater. Its range once stretched from the Nile Delta throughout the Nile River. Lake Turkana in Kenya has one of the largest undisturbed Nile crocodile populations.

Generally, the adult male Nile crocodile is between 3.5 and 5 m (11 ft 6 in and 16 ft 5 in) in length and weighs 225 to 750 kg (496 to 1,653 lb). However, specimens exceeding 6.1 m (20 ft) in length and 1,000 kg (2,200 lb) in weight have been recorded. It is the largest predator in

Africa, and may be considered the second-largest extant reptile in the world, after the saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus). Size is sexually dimorphic, with females usually about 30% smaller than males. The crocodile has thick, scaly, heavily armoured skin.

Nile crocodiles are opportunistic apex predators; a very aggressive crocodile, they are capable of taking almost any animal within their range. They are generalists, taking a variety of prey, with a diet consisting mostly of different species of fish,

reptiles, birds, and mammals. As ambush predators, they can wait for hours, days, and even weeks for the suitable moment to attack. They are agile predators and wait for the opportunity for a prey item to come well within attack range. Even swift prey are not immune to attack. Like other crocodiles, Nile crocodiles have a powerful bite that is unique among all animals, and sharp, conical teeth that sink into flesh, allowing a grip that is almost impossible to loosen. They can apply high force for extended periods of time, a great advantage for holding down large prey underwater to drown.

Nile crocodiles are relatively social. They share basking spots and large food sources, such as schools of fish and big carcasses. Their strict hierarchy is determined by size. Large, old males are at the top of this hierarchy and have first access to food and the best basking spots. Crocodiles tend to respect this order; when it is infringed, the results are often violent and sometimes fatal. Like most other reptiles, Nile crocodiles lay eggs; these are guarded by the females but also males, making the Nile crocodiles one of few reptile species whose males contribute to parental care. The hatchlings are also protected for a period of time, but hunt by themselves and are not fed by the parents.

The Nile crocodile is one of the most dangerous species of crocodile and is responsible for hundreds of

human deaths every year. It is common and is not endangered, despite some regional declines or extirpations in the Maghreb.

ATTACKS ON HUMANS - MOST PROLIFIC

Much of the hunting of and general animosity toward Nile crocodiles stems from their reputation as a man-eater, which is not entirely unjustified. Despite most attacks going unreported, the Nile crocodile along with the saltwater crocodile is estimated to kill hundreds (possibly thousands) of people each year, which is more than all other crocodilian species combined. While these species are much more aggressive toward people than other living crocodilians (as is statistically supported by estimated numbers of crocodile attacks), Nile crocodiles are not particularly more likely to behave aggressively to humans or regard humans as potential prey than saltwater crocodiles. However, unlike other "man-eating" crocodile species, including the saltwater crocodile, the Nile crocodile lives in close proximity to human populations through most of its range, so contact is more frequent. This combined with the species' large size creates a higher risk of attack. Crocodiles as small as 2.1 m (6 ft 11 in) are capable of overpowering and successfully preying on small apes and hominids, presumably including children and smaller adult humans, but a majority of fatal attacks on humans are by crocodiles reportedly exceeding 3 m (9 ft 10 in) in length.

In studies preceding the slaughter of crocodiles for the leather trade, when there were believed to be many more Nile crocodiles, a roughly estimated 1,000 human fatalities per annum by Nile crocodiles were posited, with a roughly equal number of aborted attacks. A more contemporary study claimed the number of attacks by Nile crocodiles per year as 275 to 745, of which 63% are fatal, as opposed to an estimated 30 attacks per year by saltwater crocodiles, of which 50% are fatal. With the Nile crocodile and the saltwater crocodile, the mean size of crocodiles involved in non-fatal attacks was about 3 m (9 ft 10 in) as opposed to a reported range of 2.5–5 m (8 ft 2 in – 16 ft 5 in) or larger for crocodiles responsible for fatal attacks. The average estimated size of Nile crocodiles involved in fatal attacks is 3.5 m (11 ft 6 in). Since a majority of fatal attacks are believed to be predatory in nature, the Nile crocodile can be considered the most prolific predator of humans among wild animals. In comparison, lions, in the years from 1990 to 2006, were responsible for an estimated one-eighth as many fatal attacks on humans in Africa as were Nile crocodiles. Although Nile crocodiles are more than a dozen times more numerous than lions in the wild, probably fewer than a quarter of living Nile crocodiles are old and large enough to pose a danger to humans. Other wild animals responsible for more annual human mortalities either attack humans in self-defense, as do venomous snakes, or are deadly only as vectors of disease or infection, such as snails, rats and mosquitos.

Regional reportage from numerous areas with large crocodile populations nearby indicate, per district or large village, that crocodiles often annually claim about a dozen or more lives per year. Miscellaneous examples of areas in the last few decades with a dozen or more fatal crocodile attacks annually include Korogwe District, Tanzania, Niassa Reserve, Mozambique, and the area around Lower Zambezi National Park, Zambia. Despite historic claims that the victims of Nile crocodile attacks are usually women and children, there is no detectable trends in this regard and any human, regardless of age, gender, or size is potentially vulnerable. Incautious human behavior is the primary drive behind crocodile attacks. Most fatal attacks occur when a person is standing a few feet away from water on a non-steep bank, is wading in shallow waters, is swimming or has limbs dangling over a boat or pier. Many victims are caught while crouching, and people in jobs that might require heavy usage of water, including laundry workers, fisherman, game wardens and regional guides, are more likely to be attacked. Many fisherman and other workers who are not poverty-stricken will go out of their way to avoid waterways known to harbor large crocodile populations.

Most biologists who have engaged in months or even years of field work with Nile crocodiles, including Cott (1961), Graham and Beard (1968) and Guggisberg (1972), have found that with sufficient precautions, their own lives and the lives of their local guides were rarely, if ever, at risk in areas with many crocodiles. However, Guggisberg accumulated several earlier writings that noted the lack of fear of crocodiles among Africans, driven in part perhaps by poverty and superstition, that caused many observed cases of an "appalling" lack of caution within view of large crocodiles, as opposed to the presence of bold lions, which engendered an appropriate panic. Per Guggisberg, this disregard (essentially regarding the crocodile as a lowly creature and thus non-threatening to humans) may account for the higher frequency of deadly attacks by crocodiles than by large mammalian carnivores. Most locals are well aware of how to behave in crocodile-occupied areas, and some of the writings quoted by Guggisberg from the 19th and 20th century may need to be taken with a "grain of salt".

STAFF

OF LIFE

The Nile is one of the most important rivers in Africa, but when the River is mentioned one might quickly

conjure up images of Egypt. It had a spiritual connotation for the

ancient Egyptians as well as the Pharaohs.

Most of Egypt’s settlements are located along the banks of the

River

Nile. After crossing more than nine countries and a desert, the River Nile finally drains into the

Mediterranean

Sea.

The Nile crocodile is the largest crocodilian in Africa, and is generally considered the second-largest crocodilian after the saltwater crocodile. Typical size has been reported to be as much as 4.5 to 5.5 m (14 ft 9 in to 18 ft 1 in), but this is excessive for actual average size per most studies and represents the upper limit of sizes attained by the largest animals in a majority of populations. Alexander and Marais (2007) give the typical mature size as 2.8 to 3.5 m (9 ft 2 in to 11 ft 6 in); Garrick and Lang (1977) put it at from 3.0 to 4.5 m (9 ft 10 in to 14 ft 9 in).

According to Cott (1961), the average length and weight of Nile crocodiles from Uganda and Zambia in breeding maturity was 3.16 m (10 ft 4 in) and 137.5 kg (303 lb). Per Graham (1968), the average length and weight of a large sample of adult crocodiles from Lake Turkana (formerly known as Lake Rudolf),

Kenya was 3.66 m (12 ft 0 in) and body mass of 201.6 kg (444 lb). Similarly, adult crocodiles from Kruger National Park reportedly average 3.65 m (12 ft 0 in) in length. In comparison, the saltwater crocodile and gharial reportedly both average around 4 m (13 ft 1 in), so are about 30 cm (12 in) longer on average, and the false gharial (Tomistoma schlegelii) may average about 3.75 m (12 ft 4 in), so may be slightly longer, as well. However, compared to the narrow-snouted, streamlined gharial and false gharial, the Nile crocodile is more robust and ranks second to the saltwater crocodile in total average body mass among living crocodilians, and is considered to be the second-largest extant reptile.

The largest accurately measured male, shot near Mwanza, Tanzania, measured 6.45 m (21 ft 2 in) and weighed about 1,043–1,089 kg (2,300–2,400 lb). Another large male measuring 5.8 m (19 ft 0 in) in total length (Cott 1961) was among the largest Nile crocodiles ever recorded. It was estimated to weigh 1,082 kg (2,385 lb).