The

Mediterranean Sea allowed for trade and cultural exchange between Egypt and other peoples of the region. The Mediterranean Sea reached many areas of the ancient world known as the "Cradle of Civilization."

This expansive body of water provided a natural barrier between ancient Egypt and the rest of the known world. Fishing was plentiful in the Mediterranean Sea and contributed to Egypt's

prosperity.

According to a report published in 2017 by the

European

Commission, 85% of fish stocks are fished in unsustainable conditions in the Mediterranean, and 64% are

overfished to the point of risking collapse in the coming years.

Food

security is politics. Fishing should have geographical limits

imposed, linked to fuel consumption, to check where fish has

been caught. Such as to prevent unsustainable fishing practices.

International policies and policing is necessary to prevent

expansion and poaching of fish stocks, to sustain economic

growth of kleptocratic empire building.

The

bottom dollar is food. Food will become currency more and more,

as population growth continues - and each country looks to

resources belonging to other nations - to fuel unsustainable

growth. Experience has shown us that once fished out, fisheries

do not regenerate. If we allow that to happen, it is not worth

much to be able to say: "we told you so."

CMSY is a statistical model for estimating the maximum sustainable yield for a marine species in a certain area.

Conceived and developed by ISTI CNR, CMSY will be used to provide the European Commission with precise information about catch limits for fishery. Renowed international organisations such as ICES, the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea, and FAO, Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, evaluated 'CMSY' as the best model currently available.

The model stems from the close collaboration between Gianpaolo Coro, CNR–ISTI, and Rainer Froese, leading researcher of the GEOMAR institute in Kiel, in the context of the iMarine project. Gianpaolo Coro was responsible for conceiving and developing the model, while Rainer Froese worked on biological aspects. 'CMSY' is based on the combination of a Monte Carlo method with a complex Bayesian model.

The model is perfect for scenarios where limited data on a species are available. The only input needed for the model is historical data on the catch of the species and a qualitative evaluation (low, medium or high) of its natural reproductive capacity and recovery (resilience and productivity, according to the biological jargon).

The model was presented at the WKLife4 meeting organised by ICES in October 2014. During this yearly meeting, ICES selected the best model presented by biologists and modellers. CMSY was awarded the best one and the results have been published in an official report of the European Commission.

The model has also been evaluated by FAO, confirming its pioneering status.

'CMSY' will be used in coming years to establish the catch limits on fishery within the seas of northern Europe by contributing to the European economy. The model is also available on the

D4Science

Infrastructure.

FISHING

TODAY - FOOD UNFOLDED JULY 6 2021 “The situation in the Mediterranean is tragic, but we’re still

overfishing,” says Gianpaolo Coro, researcher at Cnr-Isti. Coro is one of the members of the independent and international research team whose studies informed the European Commissions’ report. The team has developed the most widely used mathematical model (CMSY) to estimate the health of fish stocks.4 According to the model, fishing is sustainable if it allows fish populations to remain constant, in equilibrium – in other words, fishing is sustainable only if the amount of fish caught still allows for a fish population to fully repopulate in a year. “When the population falls below a certain threshold, which is different depending on the fish stock, fish stops reproducing,” Coro explains.

INDUSTRIAL Vs SMALL-SCALE FISHING

In the last 20 years, more and more industrial fishing boats have joined small local fishermen in the Mediterranean (and, in many cases, have replaced them). These have often come after having depleted fish from other regions.5 “At the beginning of the 2000s, industrial fishing boats from China and Japan arrived here looking for

bluefin

tuna. They would even keep the tuna in special pools on the boat, and bring it back home alive,” says Elia Orecchia, local fisherman from Genoa, Italy.

Orecchia works on a small fishing boat together with his father, cousins, nephews, and sister. “If we suddenly didn’t have this employment, our family would die,” he says. Today, small fishing boats – those under 12 meters in length – are responsible for only 5% of all the fish removed from EU waters. Industrial

fishing, on the other hand, grows and behaves like an insatiable predator, always tending to exhaust its resources.

Small-scale fishing would offer obvious social benefits from more employment per catch, but it is the most affected by the depletion of marine biodiversity. Industrial fishing boats, with their enormous nets, can fish the little that is left more easily. “You can’t afford to remove so many tons of

fish in just a few hours. We have nothing left, it is logical those are not fishermen,” says Orecchia, “They are like people working in factories. The people you find on those huge boats may have a thousand qualifications, but they are not fishermen. It’s another world.”

4 WAYS TO STOP UNSUSTAINABLE FISHING

1. FISHING RESTRICTIONS

There’s some good news – fish reproduce relatively quickly, and marine life could replenish itself if only we gave it time to do so. Coro’s study showed that if we only cut fishing hours by 20%, the amount of

fish we could source sustainably would increase by 70% by 2030.6 Instead of just cutting fishing hours indiscriminately, we could impose specific restrictions and prohibitions by type of fishing in specific areas. “The sustainability of a type of fishing depends on the place where it is practiced,” says Coro.

2. MORE TRANSPARENCY & TRACEABILITY

In order to better understand the impact of different fishing practices in different areas, however, there is an urgent need for more transparency and traceability. A step forward has been taken thanks to the introduction of GPS systems (which make it possible to identify all ships present at sea in any given moment)7 and thanks to increasingly strict data collection systems. But a systematic analysis of the behaviour of the fleets and their impact has not yet been done. “There are large stock assessments that are often not very transparent from the point of view of the models and data used,” says Coro. Even according to Manuel Barange, the director of FAO’s

fisheries and

aquaculture department, the FAO data itself “should be interpreted primarily in terms of trends.”

Modern

piracy is fishing in territorial waters belonging to another

country. Chinese vessels — more than 700 of them in 2019 — appear to be in violation of

United Nations sanctions that prohibit foreign fishing in North Korean waters. The sanctions, imposed in 2017 in response to the country’s nuclear tests, were aimed at punishing North Korea by not allowing it to sell fishing rights in its waters in exchange for valuable foreign currency.

The new revelations cast new light on the dire lack of governance of the world’s oceans and raise thorny questions about the consequences of China’s ever-expanding role at sea and how it is connected to the nation’s geopolitical aspirations.

Estimates of the total size of China’s global fishing fleet vary widely. By some calculations, China has anywhere from 200,000 to 800,000 fishing boats, accounting for nearly half of the world’s fishing activity. The Chinese government says its distant-water fishing fleet, or those vessels that travel far from China’s coast, numbers roughly 2,600, but other research, such as this study by the Overseas Development Institute (ODI), puts this number closer to 17,000, with many of these ships being invisible like those that satellite data discovered in North Korean waters. By comparison, the United States’ distant water fishing fleet has fewer than 300 vessels.

China is not only the world’s biggest seafood exporter, the country’s population also accounts for more than a third of all fish consumption worldwide. Having depleted the seas close to home, the Chinese fishing fleet has been sailing farther afield in recent years to exploit the waters of other countries, including those in West Africa and Latin America, where enforcement tends to be weaker as local governments lack the resources or inclination to police their waters. Most Chinese distant-water ships are so large that they scoop up as many fish in one week as local boats from Senegal or Mexico might catch in a year.

China’s global fishing fleet did not grow into a modern behemoth on its own. The government has robustly subsidized the industry, spending billions of yuan annually. Chinese boats can travel so far partly because of a tenfold increase in diesel fuel subsidies between 2006 and 2011 (Beijing stopped releasing statistics after 2011, according to a Greenpeace study).

China is hardly the worst offender when it comes to such subsidies, which conservationists say, along with over-capacity of fishing vessels and illegal fishing, is a major reason that the oceans are rapidly running out of fish. The countries that provide the largest subsidies to their high-seas fishing fleets are Japan (20 percent of the global subsidies) and Spain (14 percent), followed by China, South Korea, and the U.S., according to Sala’s research.

More recently, the Chinese government has stopped calling for an expansion of its distant-water fishing fleet and released a five-year plan in 2017 that restricts the total number of offshore fishing vessels to under 3,000 by 2021.

More than seafood is at stake in the present size and ambition of China’s fishing fleet. Against the backdrop of China’s larger geo-political aspirations, the country’s commercial fishermen often serve as de-facto paramilitary personnel whose activities the Chinese government can frame as private actions. Under a civilian guise, this ostensibly private armada helps assert territorial domination, especially pushing back fishermen or governments that challenge China’s sovereignty claims that encompass nearly all of the South China Sea.

Chinese fishing boats are notoriously aggressive and often shadowed, even on the high seas or in other countries’ national waters, by armed Chinese Coast Guard vessels.

China has been looking to take over ports in the Mediterranean,

begging the question, is this to enable fish to be scooped from

this source, as other sources are fished out.

3. EAT LESS FISH

The situation won’t be resolved until we take on our responsibilities as “intensive” consumers. To save our seas, we will need to reverse our consumption trends and, more generally, the way we relate to wildlife. “We need to rethink the way we perceive food availability globally,” says Coro. Reducing our consumption, by the way, won’t mean abandoning tradition. If anything, it will mean recovering it. Our global

fish consumption has more than doubled since the 1960s.8 This means that we have gotten used to eating so much fish as a society only over the past few decades. Not only that. We have gotten used to eating the same species, on any day of the year, and very cheaply. “We have become spoiled. Every now and then some customers come asking for fish and if the fish isn’t there they get angry, they say they won’t come back then. Now everything is taken for granted,” says Orecchia.

The vegan choice, won’t be necessary. But we will have to drastically reduce our

fish

consumption, make it a more occasional treat, and in the Mediterranean, buy it as much as possible from small-scale fishing – in markets and from small fishmongers. This will also mean accepting that some species of fish might not be available at certain times and places. When we decide to eat fish, we could try different species that are more available, even if we’ve never heard of them. “For example, the Chub Mackerel, which is found here in Genoa, is not a very renowned or posh fish, but a very good one. When people say no to it, they don’t know what they’re missing,” comments Orecchia.

4. DEMAND POLITICAL ACTION

The frustrating part is that even if reducing our consumption is necessary, it won’t be enough. The relationship between fisheries and the consumer market is much more complex than it seems. “The fishing industry is not directly dependent on retail demand, and the input from consumers arrives to fisheries after a long time,” says Coro. The risk is that, even if fish consumption dropped, industrial fishing (still fueled by generous subsidies) could go on for years at the same pace.

What is needed – and what is missing – is the political will to make difficult decisions. We urgently need local and international efforts to impose more stringent regulations. As Daniel Pauly argued in his Vox article, just as the fight against tobacco in indoor public places has been won by smoking bans, and not by appeals to smokers, the fight against illegal fishing and malpractice in the fishing industry will need government-led action.

Currently, the governments of 30 countries plus the European Union make the decisions that shape 90% of global catch. The real problem, then, is that there are not enough people actively demanding political action. The fishing situation in the Mediterranean is one of the many proofs that food is not just culture, tradition, diet. Food is politics. And we are not just consumers. We are citizens. So we must apply pressure, as we can, in both guises.

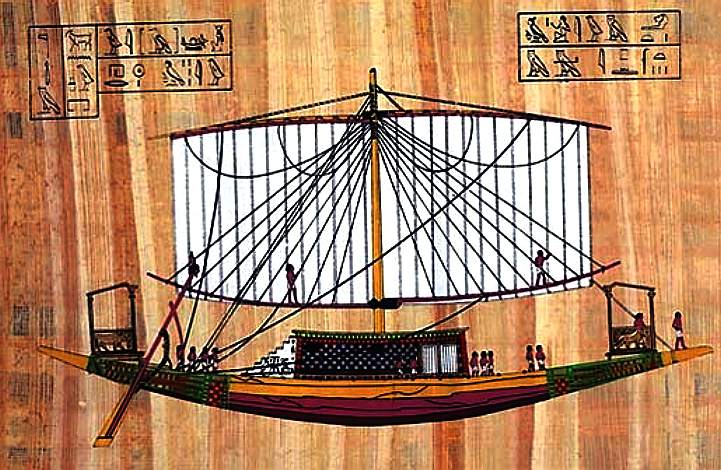

THE

NILE - Was then and is now the source of life for Egypt.

REFERENCES

https://i-marine.d4science.org/ https://www.foodunfolded.com/article/unsustainable-fishing-the-situation-in-the-mediterranean https://www.foodunfolded.com/article/unsustainable-fishing-the-situation-in-the-mediterranean 1.

Seaspiracy: Netflix documentary accused of misrepresentation by participants, Karen

McVeigh, The Guardian, 2021 https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/mar/31/seaspiracy-netflix-documentary-accused-of-misrepresentation-by-participants

2. What Netflix’s Seaspiracy gets wrong about fishing, explained by a marine biologist, Daniel

Pauly, Vox, 2021 https://www.vox.com/2021/4/13/22380637/seaspiracy-netflix-fact-check-fishing-ocean-plastic-veganism-vegetarianism

3. The state and development of the biomass of fish stocks managed by the

CFP, 8th parliamentary term Committee Hearing 27.02.2017 https://www.europarl.europa.eu/committees/en/the-state-and-development-of-the-biomass/product-details/20170202CHE00841

4. CMSY - A statistical model for sustainable fisheries in Europe, Consiglio Nazionale della

Ricerche, 2015 http://www.i-marine.eu/Content/eLibrary.aspx?id=afdd185f-3a72-48c7-b7b9-fa01eda13b99&li=0

5. How China’s Expanding Fishing Fleet Is Depleting the World’s Oceans, Ian

Urbina, Yale Environment 360, 2020 https://e360.yale.edu/features/how-chinas-expanding-fishing-fleet-is-depleting-worlds-oceans

6. Froese Report Factsheet - Towards the Recovery of European Fisheries,

Oceana, 2016 https://europe.oceana.org/en/publications/reports/froese-report-factsheet-towards-recovery-european-fisheries

7. Marine Traffic - Global Ship Tracking Intelligence https://www.marinetraffic.com/en/ais/home/centerx:-12.0/centery:25.0/zoom:4

8. Rising incomes, increased urbanization to underpin seafood consumption growth, Jason Holland,

SeafoodSource, 2019 https://www.seafoodsource.com/news/supply-trade/rising-incomes-increased-urbanization-to-underpin-seafood-consumption-growth

|