|

Map of the Spanish Caribbean

Islands 1600 Spanish Overseas territories Northern America Turks and

Caicos Islands (1492-1516, 1516-1678) * Islas Turcas y Caicos The

Bahamas (1492-1516, 1516-1648) *Islas Lucayas Bermuda (1503-1516,

1516-1609) *Carabela/Isla de los Diablos Greater Antilles Cuba

(1492-1762, 1763-1898) *Juana Cayman Islands (UK) (1503-1670) *Islas de

las Tortugas La Española/Hispanola (1492-1795, 1801-1822) Dominican

Republic (1492-1795, 1801-1822, 1861-1863) *Santo Domingo Haiti

(1492-1793) *Santa María Jamaica (1492-1655) *Isla Santiago Puerto Rico

(US) (1493-1898) *San Juan Bautista Lesser Antilles Leeward Islands:

Virgin Islands (1493-1587) *Islas Once Mil Vírgenes / Islas Vírgenes St.

Thomas (US) (1493-1587) St. John (US) (1493-1587) St. Croix (US)

(1493-1587) Water Island (US) (1493-1587) British Virgin Islands (UK)

(1493-1648) *Islas Once Mil Vírgenes / Islas Vírgenes Tortola (UK)

(1493-1648) Virgin Gorda (UK) (1493-1672) Anegada (UK) (1493-1672) Jost

Van Dyke (UK) (1493-1672) Anguilla (UK) (1500-1631, 1631-1650) *Isla de

la Anguila Saint Martin/Sint Maarten (France/Neth.) (1493-1631) *San

Martín Saint-Barthélemy (Fr.) (1493-1648) *San Bartolomeo Saba (Neth.)

(1493-1640) *Saba/San Cristóbal Sint Eustatius (Neth.) (1493-1640) *San

Eustaquio St. Kitts and Nevis (1493-1628) *Nuestra Señora de las Nieves

Saint Kitts (1493-1628) *San Cristóbal Nevis (1493-1628) *Nieves Antigua

and Barbuda Barbuda (1493-1628) *Santa Dulcina Antigua (1493-1632)

*Santa María de la Antigua Redonda (1493-1632) *Santa María la Redonda

Montserrat (UK) (1493-1632) *Santa María de Monstserrat Guadeloupe (Fr.)

(1493-1631) *Santa Guadalupe Windward Islands: Dominica (1493-1635)

*Domingo Martinique (Fr.) (1502-1635) *Martinino Saint Lucia (St. Lucia)

(1502-1660) *Santa Lucía Barbados (1492-1620) *Los Barbados/El Barbudo

St. Vincent and the Grenadines (1498-1627) *San Vicente Saint Vincent

the Grenadines Grenada (1498-1650) *Concepción Carriacou & Petite

Martinique (Grenada) Trinidad & Tobago (1498-1628) *Santísima e

Asunción Aruba (Neth.) (1499-1648) *Aruba/Oroba Curaçao (Neth.)

(1499-1634) *Curasao/Isla de los Gigantes Bonaire (Neth.) (1499-1635) *

Bonaire/Buon Aire Viceroyalty of New Granada Los Roques Archipelago

(Ven) La Orchila (Ven) La Tortuga (Ven) La Blanquilla (Ven) Margarita

Island (Ven) Coche (Ven) Cubagua (Ven) Other islands (Ven) *Founded

Spanish names

The

Caribbean

Sea is littered with shipwrecks and dotted with dozens of paradise

islands, where

pirates

might have buried their treasure. It is also awash with Sargassum, that

washes up on shores to ruin tourism and beach ecology. The proliferate

seaweed has spread from the Sargassum Sea to the South Atlantic, mainly

because of nutrient leaching from agricultural activity on land, and warming

of the acid oceans. Leading to a bumper crop, that at the moment, is not

harvested.

The

Guantanamo Bay detention camp (Spanish: Centro de detención de la bahía de Guantánamo)

in this fictional John

Storm ocean adventure, is a United States military prison within the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, also referred to as Gitmo, on the coast of Guantánamo Bay in Cuba.

Cuba

- Is the largest island in the Caribbean by size, with just

over 11 million inhabitants.

ISLANDS

BY

POPULATION

1

Cuba 11,252,999

2 Haiti

11,263,077 (Hispaniola)

3 Dominican Republic 10,766,998 (Hispaniola)

4 Puerto Rico (US) 3,508,000

5 Jamaica 2,729,000

6 Trinidad and Tobago 1,357,000

7 Guadeloupe (France) 405,000

8 Martinique (France) 383,000

9 Bahamas 379,000

10 Barbados 283,000

11 Saint Lucia 172,000

12 Curaçao (Netherlands) 157,000

13 Aruba (Netherlands) 110,000

14 Saint Vincent and the Grenadines 110,000

15 United States Virgin Islands

105,000

16 Grenada 104,000

17 Antigua and Barbuda 89,000

18 Dominica 71,000

19 Cayman Islands (UK) 59,000

20 Saint Kitts and Nevis 46,000

21 Sint Maarten (Netherlands) 39,000

22 Turks and Caicos Islands (UK) 37,000

23 Saint Martin (France) 36,000

24 British Virgin Islands (UK) 31,000

25 Caribbean Netherlands

26,000

26 Anguilla (UK) 14,000

27 Saint Barthélemy (France) 10,000

28 Montserrat (UK) 5,000

29

Tortuga 25,936

30

Roatán 110,000

31

Povidencia

Isla

32

Dead

Chest Island (uninhabited)

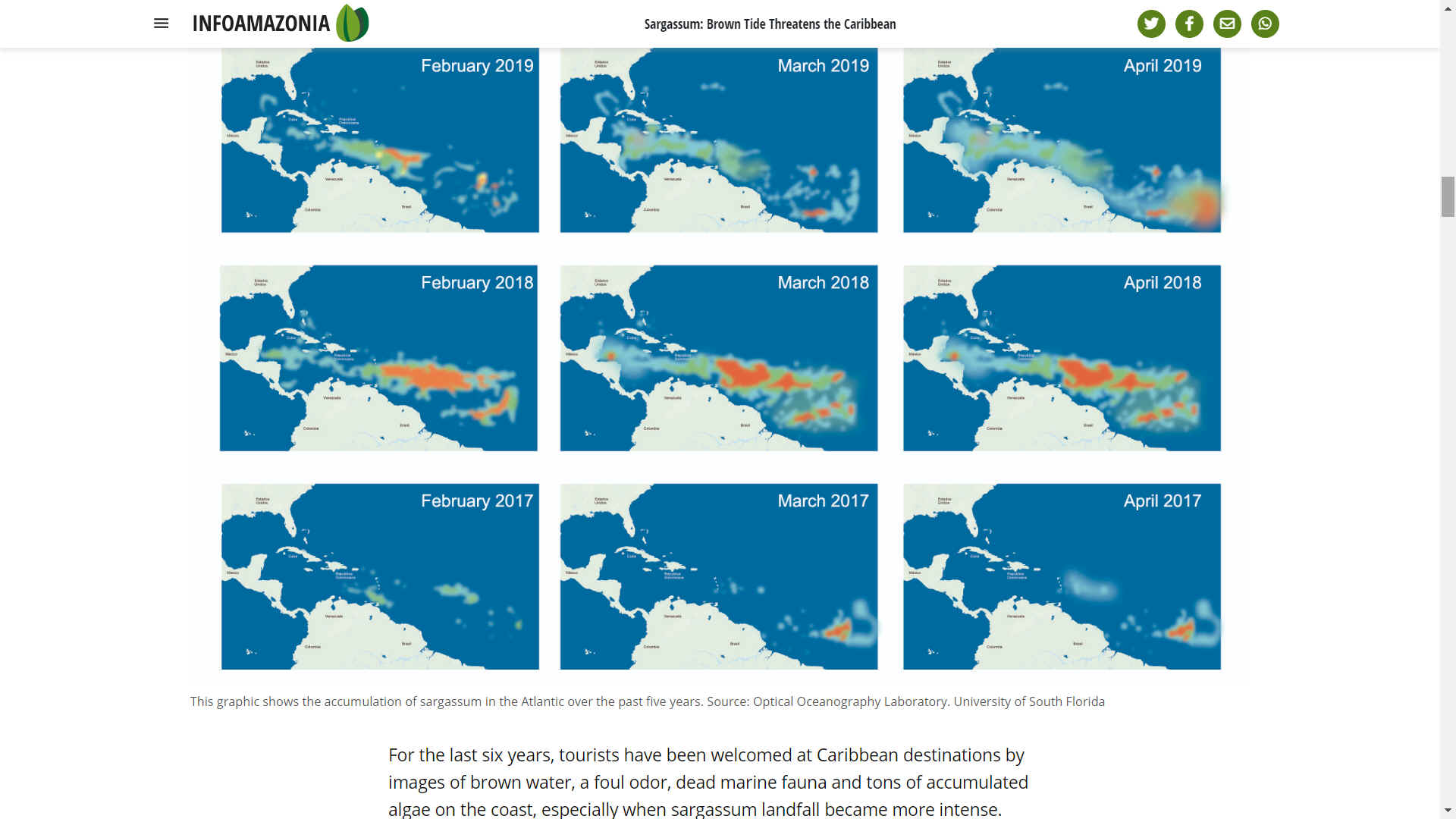

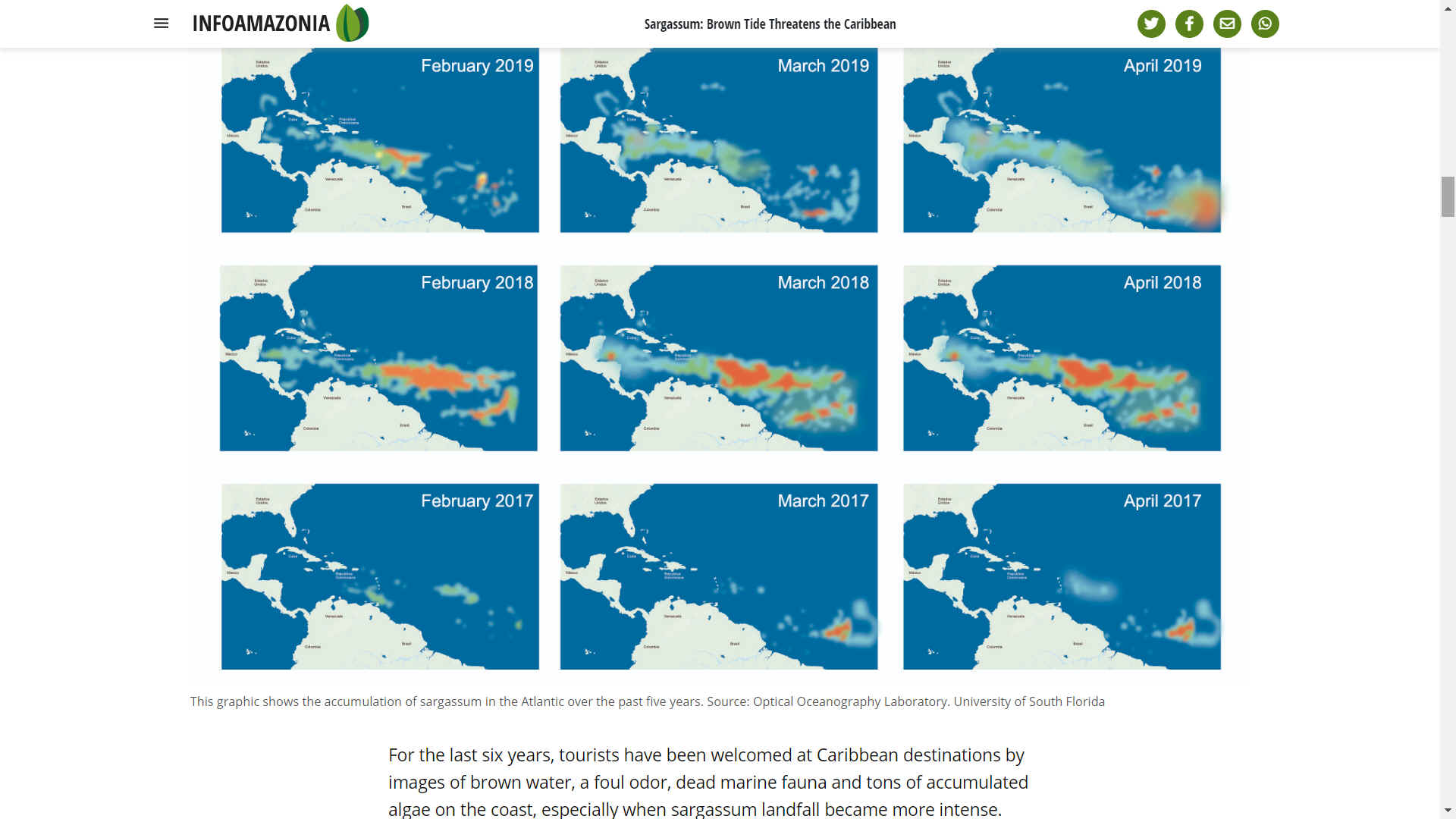

The

New Sargassum Sea is clearly visible, and a growing concern, stemming from global

warming and fertilizer run off

CARIBBEAN ISLANDS - WEST INDIES

The region, situated largely on the Caribbean Plate, has more than

700 islands, islets, reefs and cays (see the list of Caribbean islands).

Three island arcs delineate the eastern and northern edges of the

Caribbean Sea: The Greater Antilles to the north, and the Lesser

Antilles and Leeward Antilles to the south and east. Together with the

nearby Lucayan Archipelago, these island arcs make up the West Indies.

The Bahamas and the Turks and Caicos Islands are sometimes

considered to be a part of the Caribbean, even though they are neither

within the

Caribbean Sea

nor on its border. However, The Bahamas is a full member state of the

Caribbean Community and the Turks and Caicos Islands are an associate

member. Belize, Guyana, and Suriname are also considered part of the

Caribbean despite being mainland countries and they are full member

states of the Caribbean Community and the Association of Caribbean

States. Several regions of mainland North and South America are also

often seen as part of the Caribbean because of their political and

cultural ties with the region. These include Belize, the Caribbean

region of Colombia, the Venezuelan Caribbean, Quintana Roo in Mexico

(consisting of Cozumel and the Caribbean coast of the Yucatán

Peninsula), and The Guianas (Guyana, Suriname, French Guiana, Guayana

Region in Venezuela, and Amapá in Brazil).

The islands of the Caribbean (the West Indies) are often regarded as

a subregion of North America, though sometimes they are included in

Middle America or then left as a subregion of their own and are

organized into 30 territories including sovereign states, overseas

departments, and dependencies. From 15 December 1954, to 10 October

2010, there was a country known as the Netherlands Antilles composed of

five states, all of which were Dutch dependencies. From 3 January 1958,

to 31 May 1962, there was also a political union called the West Indies

Federation composed of ten English-speaking Caribbean territories, all

of which were then British dependencies.

These islands include active volcanoes, low-lying atolls, raised

limestone islands, and large fragments of continental crust containing

tall mountains and insular rivers. Each of the three archipelagos of the

West Indies has a unique origin and geologic composition.

SARGASSUM:

Represents a present

threat to the economics of the Caribbean Islands, the Gulf of

Mexico, and

African west coast, but is also a potential asset if it can be equitably harvested and used for:

GREATER ANTILLES

The Greater Antilles is geologically the oldest of the three

archipelagos and includes both the largest islands (Cuba, Jamaica,

Hispaniola, and Puerto Rico) and the tallest mountains (Pico Duarte,

Blue Mountain, Pic la Selle, Pico Turquino) in the Caribbean. The

islands of the Greater Antilles are composed of strata of different

geological ages including Precambrian fragmented remains of the North

American Plate (older than 541 million years), Jurassic aged limestone

(201.3-145 million years ago), as well as island arc deposits and

oceanic crust from the Cretaceous (145-66 million years ago).

The Greater Antilles originated near the Isthmian region of present

day Central America in the Late Cretaceous (commonly referred to as the

Proto-Antilles), then drifted eastward arriving in their current

location when colliding with the Bahama Platform of the North American

Plate ca. 56 million years ago in the late Paleocene. This collision

caused subduction and volcanism in the Proto-Antillean area and likely

resulted in continental uplift of the Bahama Platform and changes in sea

level. The Greater Antilles have continuously been exposed since the

start of the Paleocene or at least since the Middle Eocene (66-40

million years ago), but which areas were above sea level throughout the

history of the islands remains unresolved.

The oldest rocks in the Greater Antilles are located in Cuba. They

consist of metamorphosed graywacke, argillite, tuff, mafic igneous

extrusive flows, and carbonate rock. It is estimated that nearly 70% of

Cuba consists of karst limestone. The Blue Mountains of Jamaica are a

granite outcrop rising over 2,000 meters, while the rest of the island

to the west consists mainly of karst limestone. Much of

Hispaniola,

Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands were formed by the collision of the

Caribbean Plate with the North American Plate and consist of 12 island

arch terranes. These terranes consist of oceanic crust, volcanic and

plutonic rock.

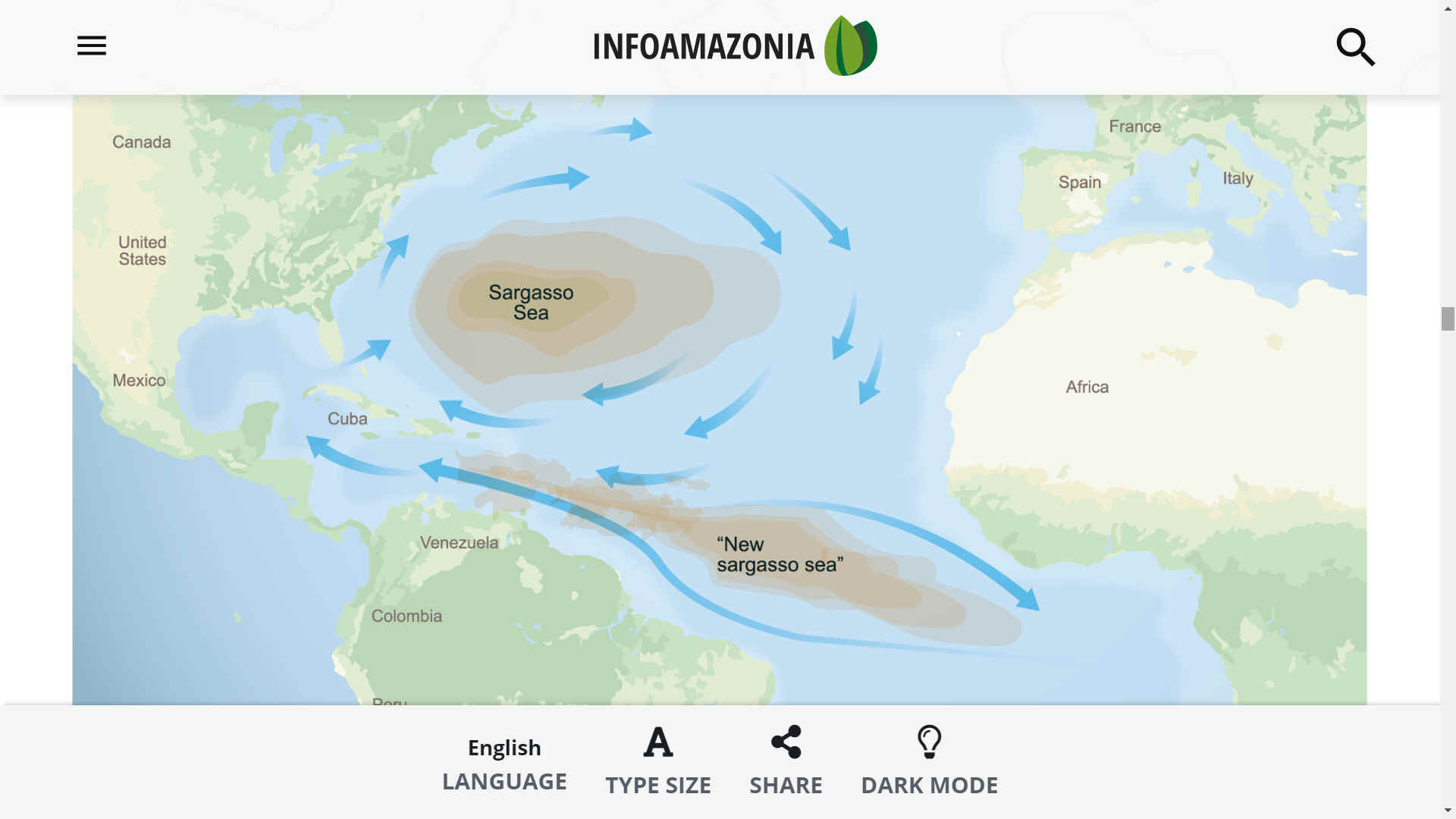

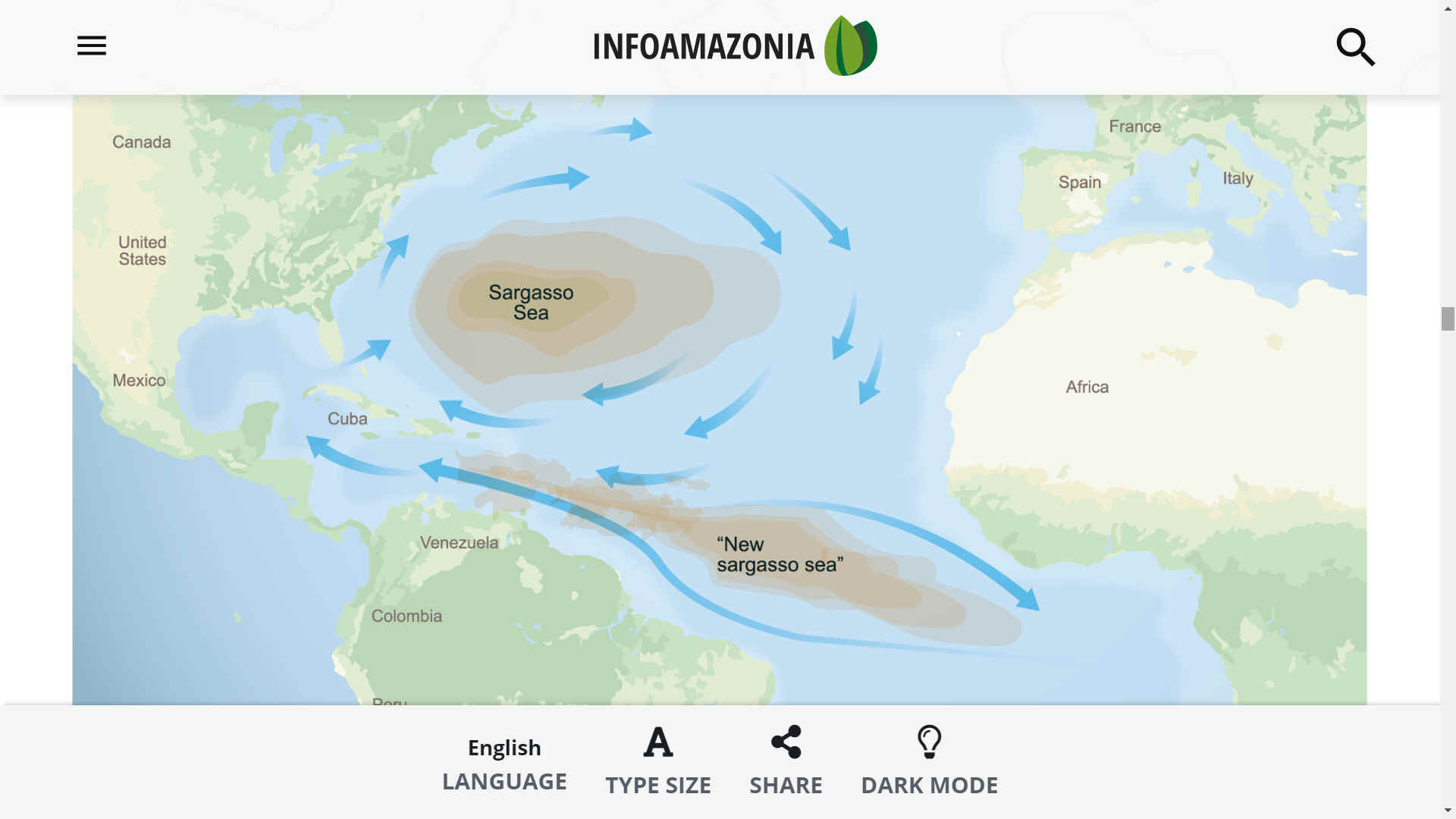

Map

of the North and South Atlantic

Oceans, showing the Sargasso Sea &

New

Sargasso Sea. The Cleaner

Ocean Foundation is concerned that as ocean

warming and acidification continues, with addition leaching of fertilizers

from

farmland, to support the growing human population (who will need food), that

sargassum migration could occur, seeding the pestilent macro algae in the Indian

and Pacific

oceans.

BIOMASS - BUILDING

MATERIALS - CANCER

TREATMENTS - CLOTHING

& SHOES - CO2

SEQUESTRATION - COSMETICS

FERTILIZERS - FOODS - MEDICINES - MINERALS - PACKAGING - SUPPLEMENTS - VITAMINS

LESSER ANTILLES

The Lesser Antilles is a volcanic island arc rising along the

leading edge of the Caribbean Plate due to the subduction of the

Atlantic seafloor of the North American and South American plates. Major

islands of the Lesser Antilles likely emerged less than 20 Ma, during

the Miocene. The volcanic activity that formed these islands began in

the Paleogene, after a period of volcanism in the Greater Antilles

ended, and continues today. The main arc of the Lesser Antilles runs

north from the coast of Venezuela to the Anegada Passage, a strait

separating them from the Greater Antilles, and includes 19 active

volcanoes.

LUCAYAN ARCHIPELAGO

The Lucayan Archipelago includes The Bahamas and the Turks and

Caicos Islands, a chain of barrier reefs and low islands atop the Bahama

Platform. The Bahama Platform is a carbonate block formed of marine

sediments and fixed to the North American Plate. The emergent islands of

the Bahamas and Turks and Caicos likely formed from accumulated

deposits of wind-blown sediments during Pleistocene glacial periods of

lower sea level.

SARGASSUM

STATE OF EMERGENCY

During

a talk at the University of West Indies, Edmund Bartlett, co-chair at

the Global Tourism Resilience and Crisis Management Center, said that

the annual cost of cleaning-up the Caribbean islands was around 120

million dollars.

Quintana Roo’s Government reported that in 2018 they removed 522,226

tons of sargassum from the public beaches and coastal zones, which

represented an investment of 17 million dollars. For 2019 and 2020 there

are no concise figures.

The mentioned amount of money is aside from what each hotel

allocates to clean-up its beach-front every day, and this cost could be

up to 60 thousand dollars annually for a medium size hotel, according to

hotel owners.

In June of 2019, the first International convention to address the

sargassum problem was held in Cancun, Mexico. At this meeting,

representatives from 13 Caribbean countries committed to working

together through public policies and knowledge production to deal with

this phenomenon. The commitment was endorsed in a second meeting held on

the island of Guadalupe in October of the same year.

NEW SARGASSO SEA

It is a relatively new phenomenon of sargassum accumulation between

the coasts of Brazil and Africa, in the South Atlantic, which some have

called “New

Sargasso

Sea.” Alfonso Aguirre Muñoz, former Director-General of the

Group of Ecology and Conservation Islands, explains that the sargassum

biomass originates along the eastern Atlantic coast of Africa and the

mouth of the Congo River and is swept along by marine currents that

circulate through tropical latitudes, passing across the mouth of the

Amazon River where it is fed by the increasing outflow of nutrients,

along the northeastern coast of Brazil, finally reaching the Caribbean

Sea and continuing on to the coast of Florida through the Gulf of

Mexico.

Caribbean waters are historically “oligotrophic”, meaning they

typically have a very low nutrient load, hence its picturesque blue

color and legendary transparency. But when the sargassum algae reach the

coast, they completely transform ecosystems and landscape.

Since 2015, some Caribbean countries have taken measures to mitigate

the effects of sargassum on the coasts. In Mexico, the Secretariat of

Environment and Natural Resources (Semarnat, by its acronym in Spanish)

issued a series of guidelines for the treatment of algae that turned

into non-formal standards. For example, burying sargassum in the sand is

prohibited – a recurring practice until 2018. There is a specific

machinery allowed to collect sargassum, so it does not damage sea

turtles and algae must be taken to a proper waste disposal.

However, the coasts already show visible impacts.

Hydrogeologist Guadalupe Velazquez, from the Research Center for

Sustainable Development (Cides, by its acronym in Spanish), indicates

that in the town of Puerto Morelos in Quintana Roo, beaches have

suffered from serious erosion and compaction, because in the process of

removing algae, many kilos of sand are also taken away, in addition to

the pressure caused by the continuous crossing of machinery.

The problems caused by the excessive landfall of sargassum do not

end when it is taken off the beach, because to date only one

municipality, Puerto Morelos, has set up a final disposal site with a

geomembrane to avoid the pollution of soil by leachates. Other

municipalities, in the best of cases, dispose of sites specifically set

up for this type of organic waste, located far from urban zones.

Alejandro López Tamayo, president of the Centinelas del Agua (Water

Sentinels) organization, explains that the Yucatan Peninsula region in

Mexico has a system of porous karstic ground, with an aquifer a few

meters deep. Without appropriate processing, the leachates released

during the rotting of sargassum rotting easily seep into the water table

and the aquifer, polluting the soil and water.

MEXICO'S MANAGEMENT TO DEAL WITH SARGASSUM

For five years, Mexican government has failed to contain or reduce

the problem. During the first years, Quintana Roo’s government,

municipalities, and hotels were in charge of the beach cleaning work.

That entailed investments of many millions of pesos to build barriers,

purchase machinery, pay workers and transport and dispose of the waste.

In 2019, the Quintana Roo´s Government Advisory Council to manage

sargassum was created, and in conjunction with members of the scientific

community and business owners, several initiatives for the integrated

management of sargassum were started, from monitoring and collection at

sea, on the beaches, to final disposal and even industrialization

(turning the waste into useful by-products). The proposed projects would

be funded with a joint contribution of the three levels of

Government.

However, because of some conflicts among the stakeholders and the

outrage arising from suspected interference from an official in the

drafting of contracts — whose connection to the alleged scandal was not

verified — the main project nicknamed “Caribbean Shield” was discarded.

Manuel López Obrador, Mexico’s President, ordered the Secretariat to

take charge of the issue, which he said he “inherited from other

governments” and which he claimed was “amplified” to criticize his

governance.

After the announced decision in June of 2019, the Secretariat of the

Navy (Semar, by its acronym in Spanish), took the lead in coordinating

strategy with Quintana Roo’s Secretariat of Ecology and Environment

(SEMA, by its acronym in Spanish) and the municipalities along the

coastline.

One of the first strategies implemented by the Semar was the

collection of sargassum in the open sea, following up on the Advisory

Council’s recommendations. Five deep draft vessels were assigned to

carry out this task.

Nevertheless, the support from the federal agency is minimal and

comes with high operational costs. From 2019 to September 2020, the

Semar reported collecting 304 tons of sargassum in the sea, barely 1.6

percent of the 18,317 tons collected on public beaches by municipal city

councils in Quintana Roo.

Sargassum represents a threat to the Mexican Caribbean tourism

industry, the most powerful in Latin America. “If a prompt solution to

the problem is not sought, consequences for the future could be

fateful,” warns Rodríguez Martínez.

Quinta Roo receives 14 million visitors annually, with a

contribution to the national Gross Domestic Product of more than 60

billion pesos, according to reports from the Tourism Secretariat

(Sectur, by its acronym in Spanish).

In order to lead the Latin American tourist market, destinations such as Cancun, Playa del Carmen, Tulum and Cozumel offer the beauty of their beaches as the main attraction.

In beaches with high sargassum concentrations, especially in the

bays and reef lagoons where the algae become stagnant, the color of the

water has changed from turquoise to brown, completely changing the

landscape even when is not the sargassum season. Examples of this

phenomenon can be found on the coasts of Puerto Morelos and Xcalak, as

well as the bays of Sian Ka’an. In addition to the environmental

problems that this represents, brown waters, like a polluted river, are

not attractive to national and foreign tourists.

SOLUTIONS STILL UNCERTAIN

Currently, there are several proposals to harvest and process the sargassum

in the Caribbean, a measure that would solve part of the problem by

transforming the algae into a resource with commercial value, according

to promoters.

One of the most advanced projects is from the company Dianco Mexico,

which will start operations in Cancun in mid April to transform

sargassum into biofertilizer. Another product they plan to produce is

cellulose.

Héctor Romero, the company’s CEO , affirms that the factory will have the capacity to process up to 600 tons of algae.

Other proposals suggest the algae can be used in the livestock feed

industry, in the cosmetic industry and to generate biofuel.

To Adán Caballero, the research available to date on the algae

of the New Sargasso Sea is not enough to establish its potential use,

because the contaminants it contains could represent a risk to public

health.

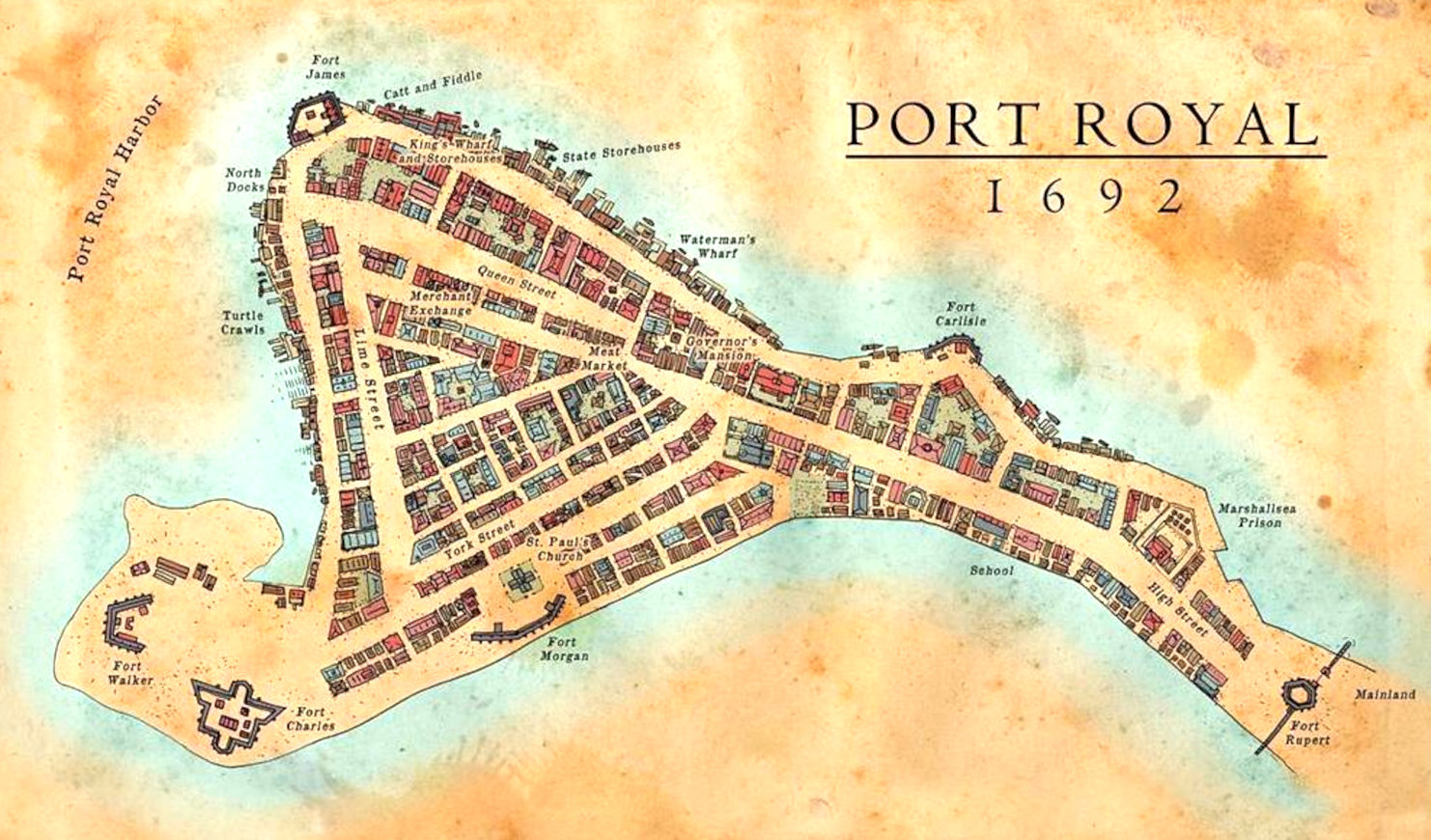

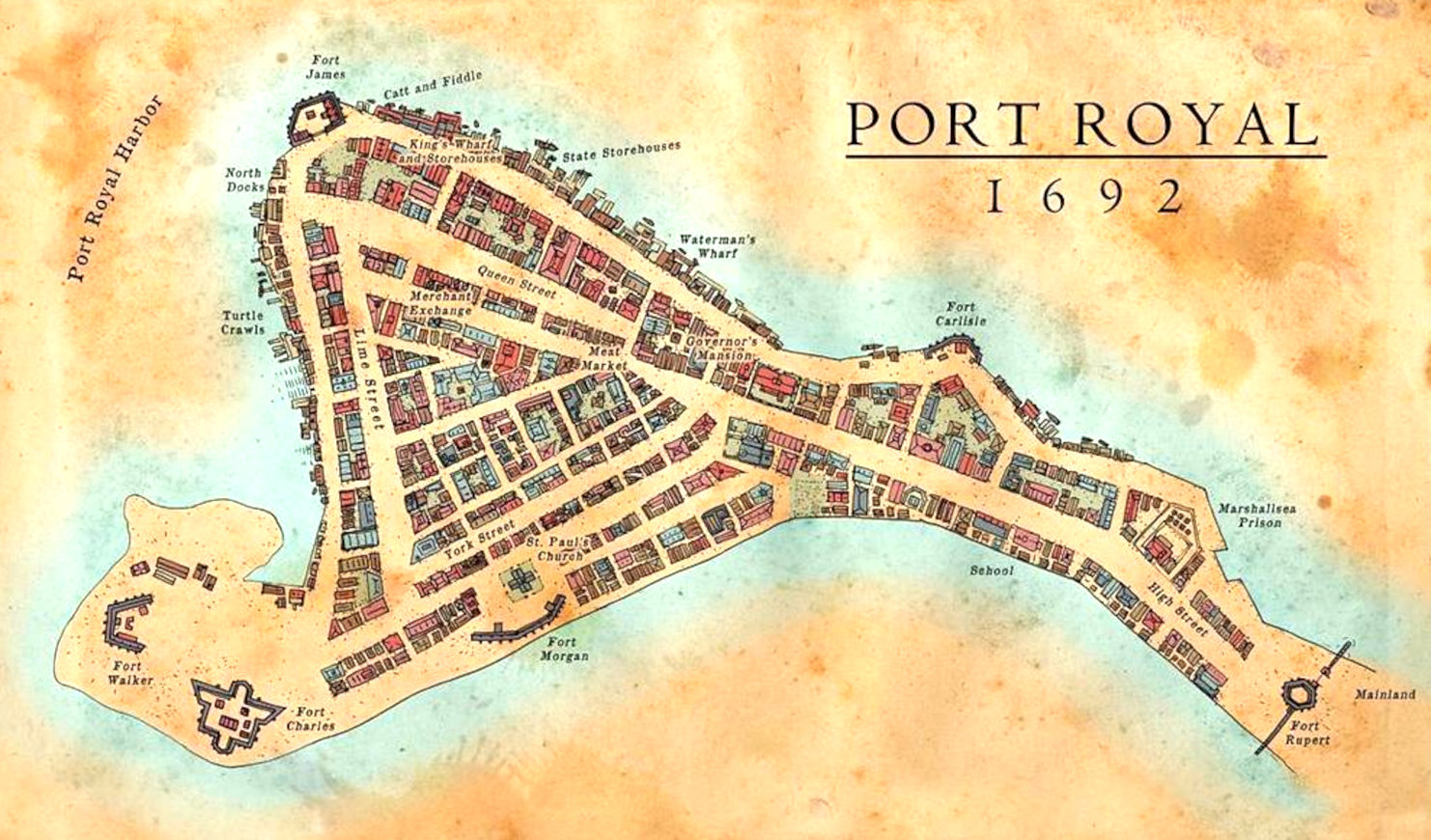

Map

of Port Royal and Kingston, where the notorious buccaneer, Sir Henry Morgan

was buried.

CITIES

LOST IN INNERSPACE

ATLANTIS

- MEDITERRANEAN SEA

ATLIT-YAM

- ISRAEL

BAIA

- ITALY

DWARKA

- INDIA

PAVLOPETRI

- GREECE

PHANAGORIA

- BLACK SEA

PORT

ROYAL - JAMAICA

RUNGHOLT

- DENMARK

THONIS-HERACLEION

AND ALEXANDRIA - EGYPT

YONAGUNI

JIMA - JAPAN

|