Maat or Maʽat comprised the ancient Egyptian concepts of truth, balance, order, harmony, law, morality, and justice. Maat was also the goddess who personified these concepts, and regulated the stars, seasons, and the actions of mortals and the deities who had brought order from chaos at the moment of creation. Her ideological opposite was Isfet (Egyptian jzft), meaning injustice, chaos, violence or to do evil.

In ancient Egyptian mythology, the Hall of Ma'at (also known as the Hall of the Two Truths or the Hall of Judgment) was the location where the dead were judged in the afterlife. Here, the deceased's heart was weighed against the feather of Ma'at, symbolizing truth and justice.

If the heart was lighter than the feather, the soul was granted passage to the paradise of Aaru (the Field of Reeds). If the heart was heavier, it was devoured by the demon Ammit, and the soul was denied eternal life.

Here's a more detailed breakdown.

Judgment in the Afterlife:

The Hall of Ma'at was a crucial part of the Egyptian afterlife, where the deceased's moral conduct during life was assessed.

Weighing of the Heart:

The central event was the weighing of the heart against the feather of Ma'at, a symbolic representation of truth and cosmic order.

Osiris and Assessors:

The god Osiris often presided over the weighing ceremony, and the 42 Assessors of Ma'at, representing different virtues, would also be present.

Consequences of the Weighing:

If the heart was lighter than the feather, the deceased was deemed righteous and allowed to proceed to Aaru. If the heart was heavier, it was consumed by Ammit, and the soul faced oblivion or a denied afterlife.

Ma'at's Importance:

Ma'at, as a concept and a goddess, represented truth, justice, cosmic order, and balance. Living in accordance with Ma'at was essential for a favorable judgment in the afterlife.

Negative Confessions:

The deceased would also recite the Negative Confessions, acknowledging the sins they had not committed during their life, further demonstrating their adherence to Ma'at.

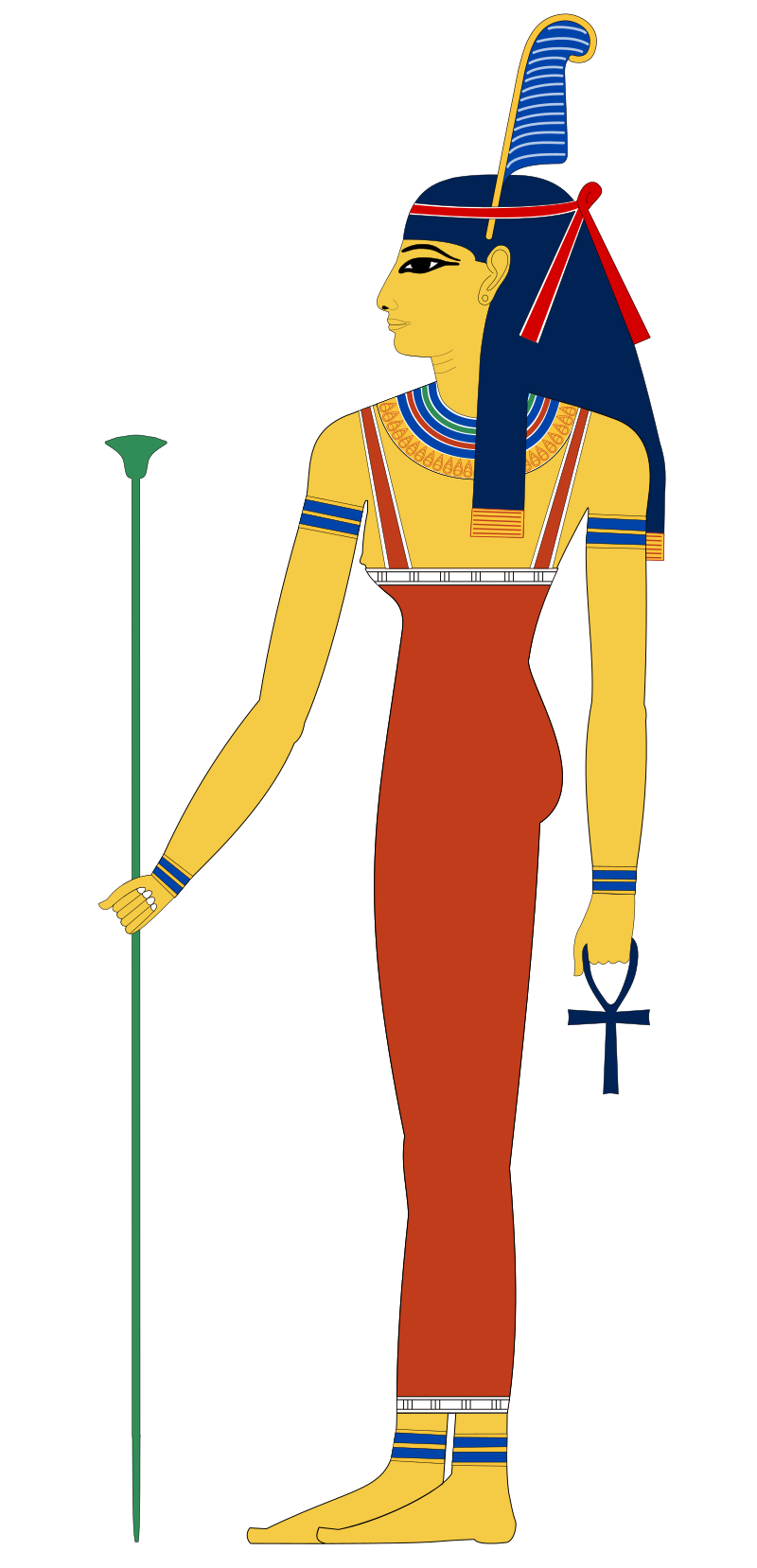

GODDESS

Maat was the goddess of harmony, justice, and truth represented as a young woman. Sometimes she is depicted with wings on each arm or as a woman with an ostrich feather on her head. The meaning of this emblem is uncertain, although the god Shu, who in some myths is Maat's brother, also wears it. Depictions of Maat as a goddess are recorded from as early as the middle of the Old Kingdom (c. 2680 to 2190 BCE).

The sun-god Ra came from the primaeval mound of creation only after he set his daughter Maat in place of isfet (chaos). Kings inherited the duty to ensure Maat remained in place, and they with Ra are said to "live on Maat", with Akhenaten (r. 1372–1355 BCE) in particular emphasising the concept to a degree that the king's contemporaries viewed as intolerance and fanaticism. Some kings incorporated Maat into their names, being referred to as Lords of Maat, or Meri-Maat (Beloved of Maat).

Maat had a central role in the ceremony of the Weighing of the Heart, where the decedent's heart was weighed against her feather.

PRINCIPLE

Maat represents the ethical and moral principle that all Egyptian citizens were expected to follow throughout their daily lives. They were expected to act with honor and truth in matters that involve family, the community, the nation, the environment, and the gods.

Maat as a principle was formed to meet the complex needs of the emergent Egyptian state that embraced diverse peoples with conflicting interests. The development of such rules sought to avert chaos and it became the basis of Egyptian law. From an early period the king would describe himself as the "Lord of Maat" who decreed with his mouth the Maat he conceived in his heart.

The significance of Maat developed to the point that it embraced all aspects of existence, including the basic equilibrium of the universe, the relationship between constituent parts, the cycle of the seasons, heavenly movements, religious observations and good faith, honesty, and truthfulness in social interactions.

The ancient Egyptians had a deep conviction of an underlying holiness and unity within the universe. Cosmic harmony was achieved by correct public and ritual life. Any disturbance in cosmic harmony could have consequences for the individual as well as the state. An impious king could bring about famine, and blasphemy could bring blindness to an individual. In opposition to the right order expressed in the concept of Maat is the concept of Isfet: chaos, lies and violence.

In addition, several other principles within ancient Egyptian law were essential, including an adherence to tradition as opposed to change, the importance of rhetorical skill and the significance of achieving impartiality and "righteous action". In one Middle Kingdom (2062 to c. 1664 BCE) text, the creator declares "I made every man like his fellow". Maat called the rich to help the less fortunate rather than exploit them, echoed in tomb declarations: "I have given bread to the hungry and clothed the naked" and "I was a husband to the widow and father to the orphan".

To the Egyptian mind, Maat bound all things together in an indestructible unity: the universe, the natural world, the state, and the individual were all seen as parts of the wider order generated by Maat.

GODS OF THE DUAT

The Duat was populated by a vast pantheon of gods and goddesses, each playing a role in the deceased's journey or in the daily cycle of cosmic regeneration. Key deities associated with the Duat include:

- Osiris: The undisputed ruler of the Duat and god of the afterlife, resurrection, and fertility. He was central to the judgment of the dead.

- Anubis: The jackal-headed god of mummification and the guide of souls through theat. He played a crucial role in the weighing of the heart ceremony.

- Thoth: The ibis-headed god of wisdom, writing, and magic. He often acted as a scribe during the judgment and provided magical protection.

- Horus: Often depicted as a falcon or a man with a falcon head, Horus was the son of Osiris and Isis. He avenged his father's death and was a symbol of kingship and divine protection.

- Isis: The great mother goddess, wife of Osiris, and mother of Horus. She was a powerful sorceress and protector of the dead.

- Ra: The sun god, who journeyed through the Duat each night, battling its dangers to be reborn each morning, symbolizing the cycle of death and rebirth that the deceased hoped to emulate.

- Sekhmet, Serqet, Neith, and Selket: Various protective goddesses who guarded specific gates or regions within the Duat.

The Amduat and the Book of the Dead are both crucial funerary texts from ancient Egypt, designed to guide the deceased through the perils of the afterlife and ensure their successful regeneration. While they share the ultimate goal of eternal existence, they differ in their focus, scope, and the nature of the "regeneration" they describe.

THE AMDUAT: THE JOURNEY OF THE SUN GOD AND ROYAL REGENERATION

The Amduat (literally, "That Which Is In the Afterworld" or "Book of the Hidden Chamber") is a highly structured and esoteric text, primarily found in royal tombs of the New Kingdom (like that of Thutmose III). Its main focus is the nocturnal journey of the sun god Ra through the 12 hours of the Duat (underworld).

- Symbolic Regeneration of Ra: The Amduat details Ra's daily cycle of death and rebirth. As the sun sets in the west, Ra is believed to "die" and descend into the underworld. Throughout the night, he navigates dangerous regions, battles chaotic forces (like the serpent Apep), and at the deepest point (around the 6th hour, midnight), he unites with the inert body of Osiris, the god of the dead. This union symbolizes the fusion of Ra's active, life-giving ba (soul/personality) with Osiris's inert khat (body) or ka (life force), allowing for the regeneration of the sun god. At the 12th hour, Ra emerges from the underworld in the east, reborn as the morning sun (often in the form of Khepri, the scarab beetle), ready to illuminate the world once more.

- Pharaoh's Parallel Journey: The Amduat served as a map and guide for the deceased pharaoh, who was believed to emulate Ra's journey. By understanding the topography of the Duat, the names of its inhabitants, and the spells to overcome obstacles, the pharaoh could successfully navigate this perilous path. The ultimate goal for the pharaoh was to unite with Ra and participate in this eternal cycle of rebirth, ensuring their own perpetual existence as a divine being.

- Focus on Cosmic Renewal: The Amduat is less about individual moral judgment and more about the cosmic renewal of the king and, by extension, the order of the universe. The king's successful passage through the Duat was essential for the continuation of creation itself.

THE BOOK OF THE DEAD: INDIVIDUAL GUIDANCE AND JUSTIFICATION

The Book of the Dead (the modern term for what the Egyptians called "The Book of Going Forth by Day") is a broader collection of spells, hymns, and prayers, much more diverse and less rigidly structured than the Amduat. It evolved over centuries and was widely used by non-royal elites and eventually even commoners, typically inscribed on papyrus scrolls placed in coffins or burial chambers.

- Practical Guide for the Deceased: Its primary purpose was to provide the deceased with the necessary knowledge, incantations, and protections to overcome the dangers of the Duat, identify benevolent deities, repel malevolent demons, and ultimately achieve a blessed afterlife.

- Emphasis on Moral Justification: A crucial aspect of the Book of the Dead is Spell 125, the "Negative Confession" and the "Weighing of the Heart" ceremony. This involved the deceased declaring their innocence of various sins before a tribunal of 42 gods and having their heart weighed against the feather of Ma'at. This moral judgment was central to an individual's justification and right to enter the afterlife.

- Regeneration into a Justified Spirit: For the individual, "regeneration" as described in the Book of the Dead typically meant being transformed into an akh – an effective, transfigured spirit that could "go forth by day" (hence the title). This akh would reside in the blissful Field of Reeds (Aaru), a perfect, idealized version of earthly life, where they would farm, feast, and enjoy eternal peace, free from suffering.

REGENERATIONS BACK INTO A PHYSICAL FORM ON EARTH?

This is a key point of distinction and a common misconception. Ancient Egyptian beliefs of regeneration generally did not involve the deceased coming back to life in their physical form on

Earth in the same way they lived before. The one exception to this rue, being Cleopatra, in invoking a curse on her enemies and praying for rebirth.

- Preservation of the Body (Mummification): The elaborate practice of mummification was crucial because the physical body (khat) was believed to be the necessary anchor for the ka (life force) and ba (soul/personality) to exist in the afterlife. The ba could travel out from the tomb, but it always needed to return to the preserved body.

- Transformation, Not Re-embodiment: The "regeneration" described in both the Amduat and the Book of the Dead was primarily a spiritual transformation and continuation of existence in a perfected, justified, and often semi-divine state.

* For the pharaoh (Amduat), it was a union with Ra and Osiris, becoming part of the eternal cosmic cycle.

* For the individual (Book of the Dead), it was becoming an akh, capable of moving freely between the tomb and the celestial realms, living in the Field of Reeds.

- No Return to Mortal Life: There is no strong evidence in ancient Egyptian funerary texts to suggest a belief in literal

reincarnation or a return to live as a mortal human on Earth again in a new physical body. The goal was to overcome death, not to repeat mortal life. The concept was about transcending mortality and entering an eternal, perfected state of being, though this state often retained elements of the deceased's former identity and activities within the blissful Field of Reeds.

In essence, the Amduat is a highly specialized, royal text about the sun god's journey and the king's assimilation into cosmic regeneration, while the Book of the Dead is a more generalized collection of spells for individuals to achieve justified eternal existence in the afterlife through moral purity and magical knowledge. Neither text speaks of a return to physical, mortal life on Earth.